You grew up in Alabama. What was it like being black when you were growing up there?

Willie Mays: The same as being black right now. I don’t think that’s different. In Birmingham at that time, everything was segregated: the movies, the restaurants, and different things. And you had the bathrooms that had “colored” and “white” on it, and all that kind of junk. So, you knew exactly what was going on, but you couldn’t do anything about it at that particular time. So, I think it affected a lot of people at that time coming along. I guess they had to accept what was going on, they couldn’t do too much about it.

In my home town, Fairfield, we used to play football and baseball together. They would stop us from playing. When I was about 12 years old we used to go down on the field and play football, and about 3 or 4 o’clock an officer would come down and break us up. We’d go our separate ways.

There had to be some anger.

Willie Mays: I was very fortunate to play sports. All the anger in me went out. I had to do what I had to do. If you stay angry all the time, then you really don’t have a good life. We knew what was going on, but again, if you just stay focused on what is happening as far as your life is concerned, I don’t think you’ll have a hard time. Sure, I went to all an all-black school. And like you said, there had to be some anger there, but what good was it going to do? Who were you going to go to?

When I had a job that I didn’t like and that wasn’t good for me, my father would say, “Hey, don’t work, you’re going to play baseball.” I really didn’t understand what he was talking about at the time. But he was saying, “I don’t want you going into this field. I don’t want you working where you don’t want to work.” So I was very fortunate.

Did anyone besides your father influence you?

Willie Mays: I had an uncle that played a great role in my life as far as sports. Like I said, in the South we would always play like three or four o’clock in the afternoon. I would have to go to school, and he would do my chores. When I say chores, that means I had to cut the wood, I had to wash the clothes; I had to do everything that everybody in the house had to do. So he would do all that stuff for me, and I was very happy about it because I wasn’t about to mess my arms up and my hands, so I could go and play ball and didn’t have to do too much.

Did anybody say anything to inspire you?

Willie Mays: Oh yeah. My uncle would say every day, “You’re going to be a baseball player. You’re going to be a baseball player, and we’re gonna see to that.” Not knowing that I was going to be a professional baseball player, but see, my life was like this. At ten I was playing against 18-year-old guys. At 15 I was playing professional ball with the Birmingham Black Barons, so I really came very quickly in all sports. Basketball was my second sport. Football was my first, baseball was my last. But I picked baseball because it was the easiest of the three. And I don’t think I had a problem with that, but the others I thought I would get hurt in, so I just picked that. And my father didn’t have money for me to go to college. And at that particular time they didn’t have black quarterbacks, and I don’t think I could have made it in basketball, because I was only 5′ 11″. So I just picked baseball. There wasn’t no height limit there in baseball. You’d just go in and play and have a good time.

There were no blacks in the major leagues then.

Willie Mays: I played with the Birmingham Black Barons. I was making 500 at 14. That was a lot of money in those days. Jackie Robinson didn’t come along until 1947, but I played in Birmingham in ’47, ’48 and ’49, and the Giants signed me in 1950. I had traveled from Chattanooga and Memphis. I had been through all parts of the country. In New York I had played with the New York Cubans. I had played against Philadelphia, and in Pittsburgh, against the Newark Eagles. I had been to all the big cities.

We had a guy by the name of Piper Davis who was the manager of the Birmingham team, and he let me go to school. My father said I had to go to school. After the school year, I would travel with the ball club. During the year, I only played on weekends. I had to go to school five days and play two days with them.

Tell us why there was a need for Negro leagues.

Willie Mays: There was a need because we couldn’t play with whites. That was segregation. I don’t think there’s a big secret about that. We had to create different things among ourselves, not just in the sports world, but all parts of life. When you bought a car you had to buy it from the right guy. When you bought a house you had to buy it on time, because you only got paid once a week. You got paid in chits in the South. You had a commissary that would only pay if you worked in that particular area.

We really had to do many, many things among ourselves, and sports was one of them that would get everybody together. And what the teams did is that, for instance, if you worked for Fairfield, or you worked for Westfield, or you worked for a company called Stockton, Sippico, all those teams — all those mills had a team. And they would play, like on Saturdays and Sundays, and they used to draw like 10 — 15,000 people. When you hit a home run they would pass the hat around and that was a big deal. So I didn’t hit home runs because I was so small. I was about 150, 160 or something, but I could run, I could field, I could throw. I had a lot of guys teach me. So when I was a bat boy — I was about ten, 12. I was the bat boy, so they let me play the last two innings at first base. So they really took good care of me. That’s why I would say I was blessed when I was coming along as a small kid.

When did you know you had this special talent?

Willie Mays: I knew that when I was ten or 12. Basketball teams in high school, you can’t play until like 11th or 12th grade. But I was playing on the high school team when I was in the ninth grade. I played one year of football, one year of basketball, one year of football. I started playing professional baseball at that time. The principal said to me, “Why don’t you quit baseball and come back and play at the high school.” I wasn’t making any money, but we used to have a full house at all times, especially when I played. My father, said, “You play where you want to play, and you do the best you can, whatever you want to do.”

How did you get to be so good, so soon?

Willie Mays: I don’t know. It wasn’t hard. It wasn’t anything that I had to look for. I could throw a football farther, could throw a baseball farther than anybody in my community, or anybody around that area. Basketball, I would score 20 points and stop, that was enough. I was probably one of the best basketball players in my area. How did I get there? I really don’t know. I just did what I had to do. Some guys that are so-called superstars can’t tell you how they do things. It’s creative, you just do it. Whatever comes out, it comes out good.

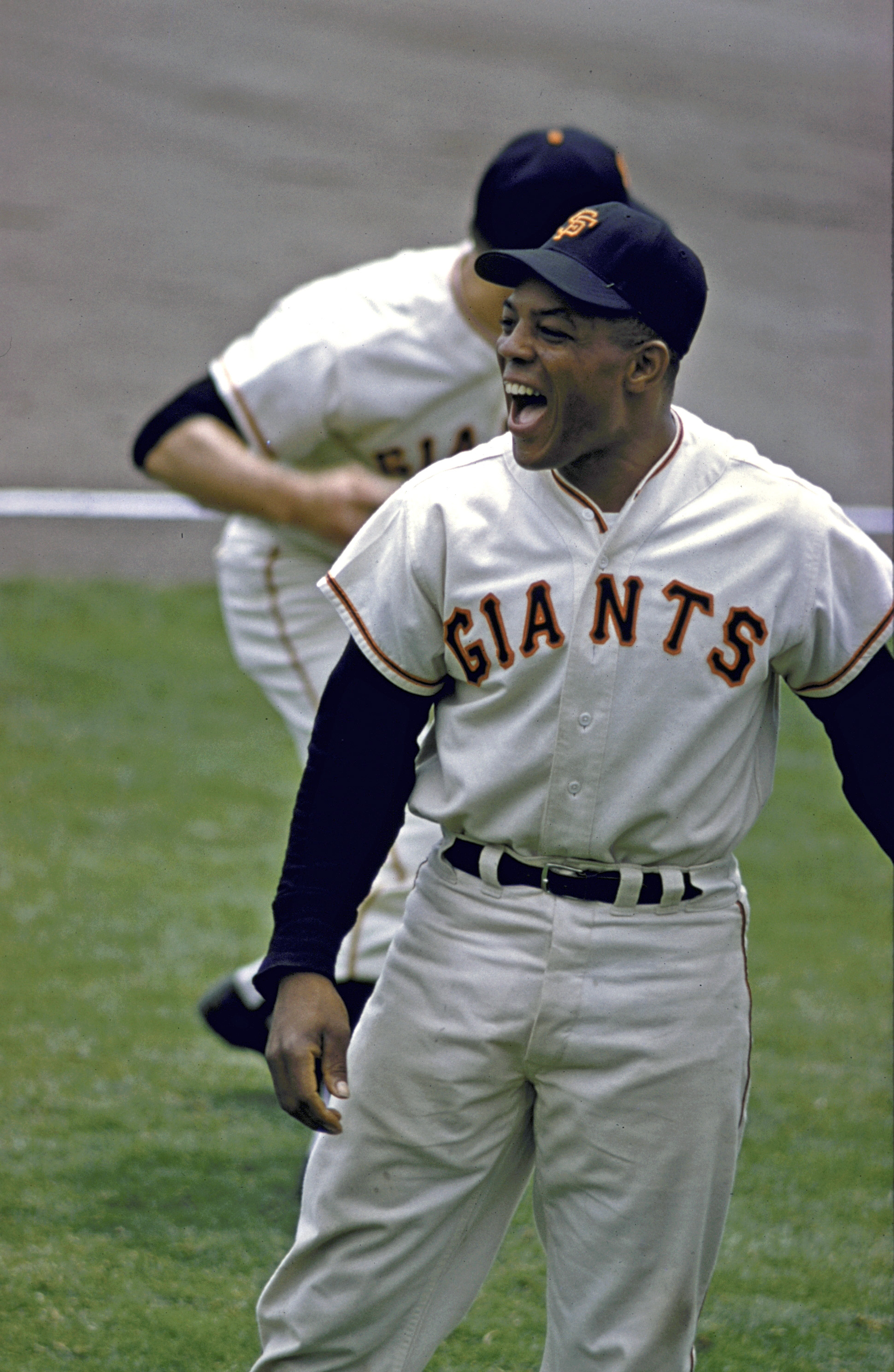

What did you like most about baseball?

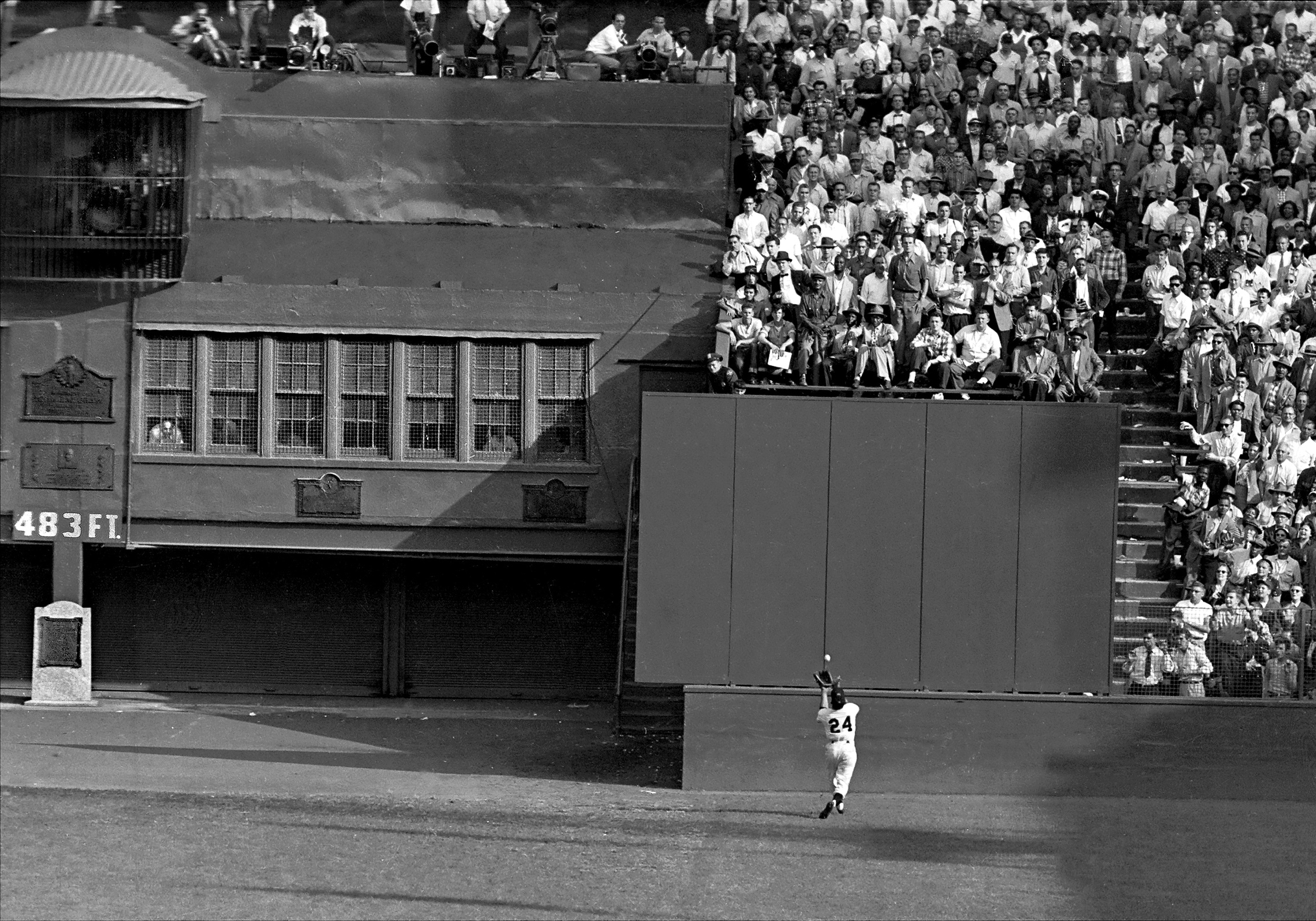

Willie Mays: Defense to me is the key to playing baseball. I know people say, “Well, you’ve got to score runs,” but you’ve got to stop them before you can score runs. And, I used to love to run down a fly ball. I used to love to throw a guy out. But of course, I played good offense too. But I just felt baseball was a beautiful game, especially at night. The sun — I mean, you had the lights out there and all you do is go out there, and you’re out there by yourself in center field, and it’s just a beautiful game. And, I just felt that it was such a beautiful game that I just wanted to play it forever, you know.

When I was in Birmingham I used to go to a place called Redwood Field. I used to get there for a two o’clock game. Where can you make this kind of money playing sports? It was just a pleasure to go out and enjoy myself and get paid for it. I didn’t understand why people didn’t want to play. When I got to professional ball I used to play 150 games every year. It depends on how many games there was. I would try and help everybody, because the game was so easy for me. It was just like walking in the park.

There must have been hard work involved. Didn’t you have to practice?

Willie Mays: I never had any training. I never had a guy say to me, “Do it this way, do it that way.” When I was growing up, I was the last guy to get picked for every team that I was on. If they needed a pitcher, I pitched. If there was a catcher needed, I caught. First baseman, shortstop, whatever position they needed, that’s what I played. I felt I was the best all-around athlete on that particular team. Most of them couldn’t do that, everybody wanted to play a position. It didn’t matter what position I played. I just had fun and enjoyed it.

Didn’t you have to work to stay in shape?

Willie Mays: Let me tell you something. I came out of the Army in 1954. I had played in the Army. I hadn’t played for I would say about five months because in Newport News, Virginia, where I was located we didn’t play from September until around April. I got out of the Army three months early. I get out (at the) end of February, I show up at spring training. I get there at 12 o’clock, the game started at 1:05. Leo said, “Go put on a uniform.” I go put on a uniform. I’m getting off the plane now. I haven’t thrown a ball, haven’t seen a ball in five months. I put it on. He said, “You want to play?” I said, “Okay. I’ll go out.” The first ball hit was over my head, against the fence. This was in Phoenix now, it was on Central Avenue. The next ball hit through the middle, I threw out a runner going in third. The next ball — then Leo said, “Gee, you want to hit?” First time up, home run.

Were you a natural athlete?

Willie Mays: I never worked at anything pertaining to sports. I think I should have. I think that all athletes should practice. They should practice because you want to know what’s happening as far as when the game is concerned. I didn’t have to do that. In spring training, when people go out running — you know, like they run laps, or around things there — I would go in and sleep. I was sleeping ’til they get through, then I would go out and run around the bases for a minute, and then I would hit. That’s my spring training. I never had any problems as far as my body was concerned. I was very blessed with a good body. Never got hurt. Never was in the hospital. The only time I was in the hospital was when I would get exhausted a little bit and go in for a check-up or something. But, I was blessed with a body that I didn’t have to do all that, you know. Like, if I went 0 for 5, or 0 for 6, I didn’t get a hit for two days, I wouldn’t take no batting practice for like two to three days because I felt I was tired. So, I would go in and just rest and go play the game. Show up — if the game was one o’clock, I show up at 12. Go play the game. Go back home, come the next day, play the game. Never practiced, never did anything.

When I got my body back together, I would go out and let the opposition see me. Only let them see me, I still can throw. That means I’m not sick, I’m just resting. That means, don’t run, I still can throw. You had to do all that in order to play sports. But my body stayed the same all the time.

Now you’re talking about young people. I think young people when they go into sports should practice. They should take all kinds of precautions with their bodies. That means get in shape. I was always in shape all year long. I never got out of shape, that was one of the keys, I think. But you have to practice. You have to know what’s going on as far as you body is concerned. You have to take orders from the manager, whatever he gives you.

I was lucky. I managed myself. Every manager that I had said, “Hey, play your game. You know what you have to do, but I have to manage the other 24 guys.” I understood what he was saying to me, but I didn’t get out of line. I didn’t make mistakes. I would have a manager like Leo, if you make a mistake: $100. If I made another mistake: $200. I used to make maybe three mistakes a year out of 154 games. Other guys could make mistakes all the time and nobody said anything, because they were supposed to make mistakes. Not me.

What about the strategies of the game?

Willie Mays: When I played I was the captain of the ball club. I would position everybody around the field. I tried to explain this to a guy one time and he says, “How’d you do all that?” I said, “Well, I had one sign.” I’d pick up my hand, and everybody was on my hand. “Go this way, this way, left, go right.” That means I want to set the left fielder up on the line, right fielder’s got to be on the line. I cover the gaps. That’s the outfield. Infielders would go spread out. That means the first baseman would cover the line, the third baseman cover the line, leave the middle open. The shortstop and second base would cover. Now they’re all in this one hand, but we’d go through it before the game starts. “Go left, go right.” That means everybody. Now, if you didn’t watch this hand, you didn’t play the next day because baseball is teamwork. It’s a team job. Everybody has to play together. Everybody has to have a little sense of what the other guy is doing.

That was the reason that I was the captain. “If you want to be the captain, you do it.” That’s what I would tell my guys. That’s how easy baseball was for me. I’m not trying to brag or anything, but I had the knowledge before I became a professional baseball player to do all these things and know what each guy would hit.

How did you know where each guy would hit?

Willie Mays: That was one of my jobs, to make sure that I knew how he would hit. The key there is how the pitcher was going to pitch. I would go over the roster with the pitcher before the game. How you’re going pitch this guy, how you’re going to pitch that guy. If the pitcher’s going to change and go another direction, he would turn to me in center field. We had three signs: one, two, three, then wipe-off. That means he’s wiping off this now, we’re going to pitch this guy another way. The pitcher, and the catcher and I would all work together. As a team, we did very well with that, when I played with the Giants.

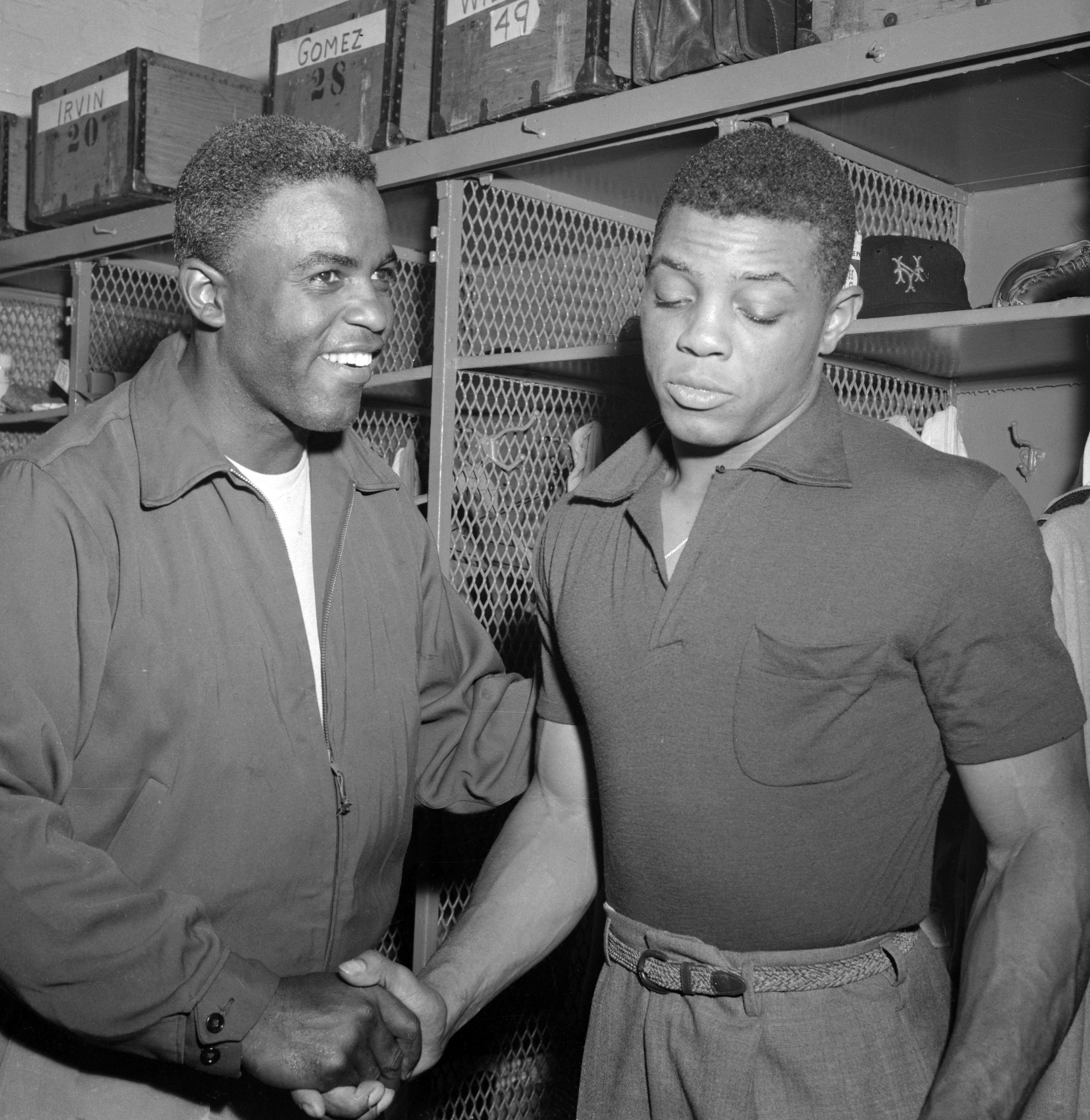

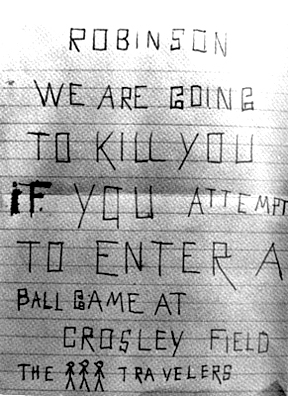

Did Jackie Robinson influence you?

Willie Mays: Robinson was important to all blacks. To make it into the majors and to take all the name calling, he had to be something special. He had to take all this for years, not just for Jackie Robinson, but for the nation. Because all eyes were on Jackie at that particular time.

We were pulling for him. When Jackie came in, I automatically became a Dodger fan, because I wanted to pull for him. I wanted to make sure that he was a very successful guy. Doby came in about two weeks after him, and he was in the American League, but we didn’t see him that much. Doby didn’t get the recognition as being the first black. I would say Jackie had more influence on, not just me, but almost all blacks in sports, or whatever.

When you were young, did you think you’d ever play in the big leagues?

Willie Mays: No. I didn’t think I would have a chance, because of segregation. I didn’t think I would ever get out of Birmingham. When they signed me they really weren’t looking at me, they were looking at a guy named Alonzo Perry. I didn’t think I was ever going to get out of there.

My father said to me, “You’re not going into a cotton field, that’s number one.” That means picking cotton down there, putting it in a sack, carrying it on your shoulder. “You’re not going to do that. You’re going to play baseball.” They always drilled that on me, “You’re going to play baseball. You’re going to be the best in baseball.” Not knowing that one day you would be. He just drilled it. I had the best shoes; I had the best glove, the best everything, as far as sports was concerned. So, my house was like a sporting goods shop. When kids didn’t have shoes, they’d come and get my shoes, wear them, bring them back. That was a community thing. So we had a good relationship in my community when I played.

In 1950, when the Giants signed me, they gave me $15,000. I bought a 1950 Mercury. I couldn’t drive, but I had it in the parking lot there, and everybody that could drive would drive the car. So it was like a community thing. Everybody knew the car, everybody knew who it was. It just was a wonderful time that I had growing up as a kid.

You must have had to give up some things, to start your professional career so young.

Willie Mays: I was in high school and I couldn’t go to my high school prom, because a guy named Chick Genove had called two days before and talked to my father. “We need him right now,” because they weren’t drawing. I said, “Dad, I’ve got to go to the prom.” He says, “Well you know, money comes first,” because I was feeding my sisters and my brothers. $15,000 was a lot of money. I really had to take a cut from 500 down to 250 to get into professional ball. I had to pay a guy to take my date to the prom that particular day, so I know the date, May 29th. It wasn’t bad. It was okay, but I didn’t want to do it. To get into the majors you had to give up a lot, you know.

What did you feel when you first played in New York?

Willie Mays: I had played there before. When I was 15 I had played in the Polo Grounds with the New York Cubans. People didn’t know that because they didn’t go and see the Negro players play all the time. So I knew about the Polo Grounds. It was no stranger to me. We had played in a lot of ball parks, but I think the strangest one, rather than the Polo Grounds was over in Brooklyn, called the Bushwick. We played under the El there. Now that was strange, more so than the Polo Grounds, because they had all these ex-players over there.

When I came back in 1951, I didn’t start in New York, I started in Philadelphia. Friday, Saturday and Sunday, that was my first game. I think I went 0 for 12, or 0 for 13, or whatever, and I’m really, really worried because in the minors I’m hitting .477, killing everybody. And I came to the majors, I couldn’t hit. I was playing the outfield very, very well, throwing out everybody, but I just couldn’t get a hit. I didn’t strike out a lot. And I started crying, and Leo came to me and he says, “You’re my center fielder; it doesn’t make any difference what you do. You just go home, come back and play tomorrow.” I think that really, really turned me around because the next day I hit a home run off of Spahn for my first hit. And, then I went another ten games, another ten at bat without getting a hit, and then I blossomed up right quick.

I should have hit around .290 my first year, but I hit .271. Twenty home runs and 74 runs scored. That was in half a season. So I did very well in my first year.

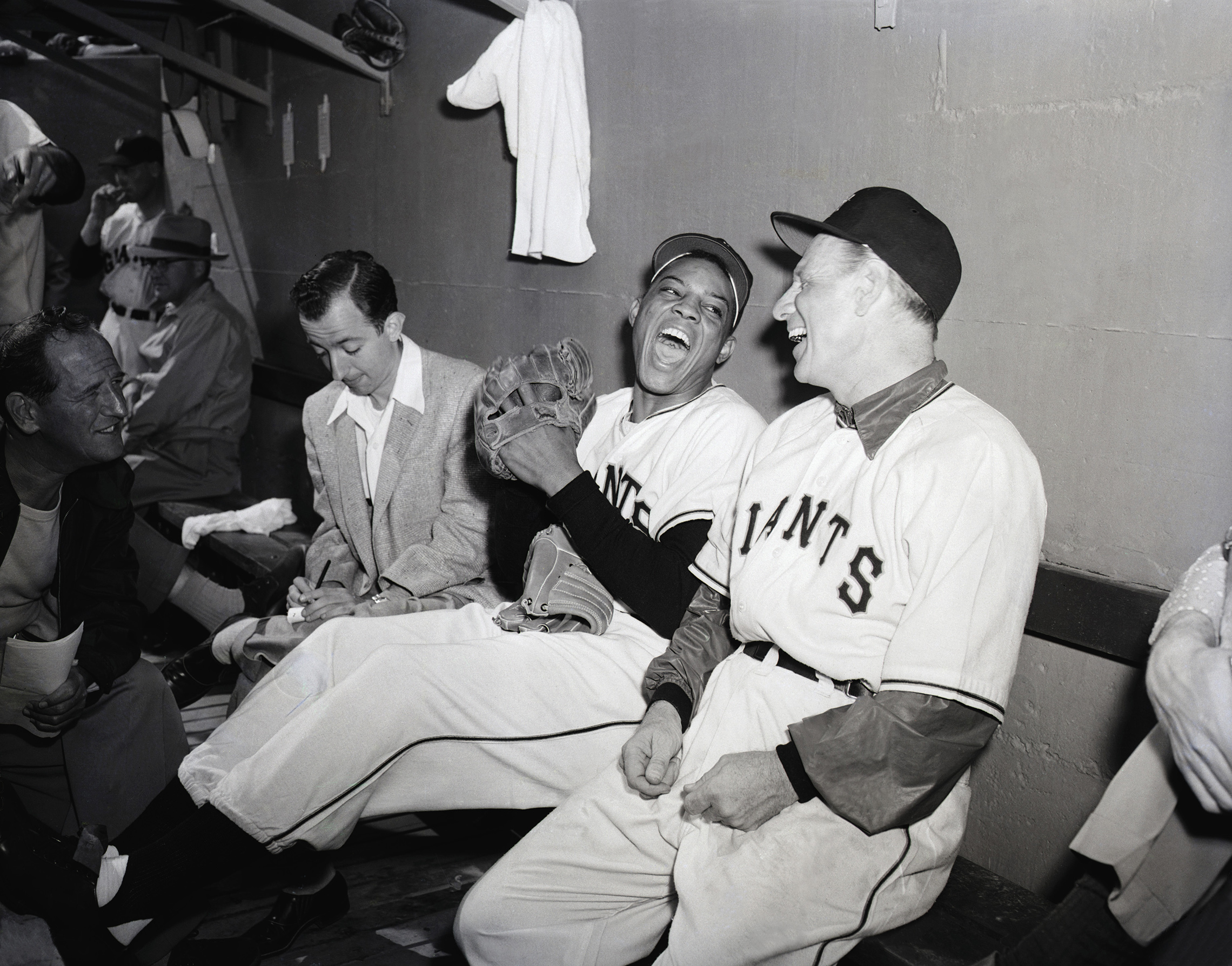

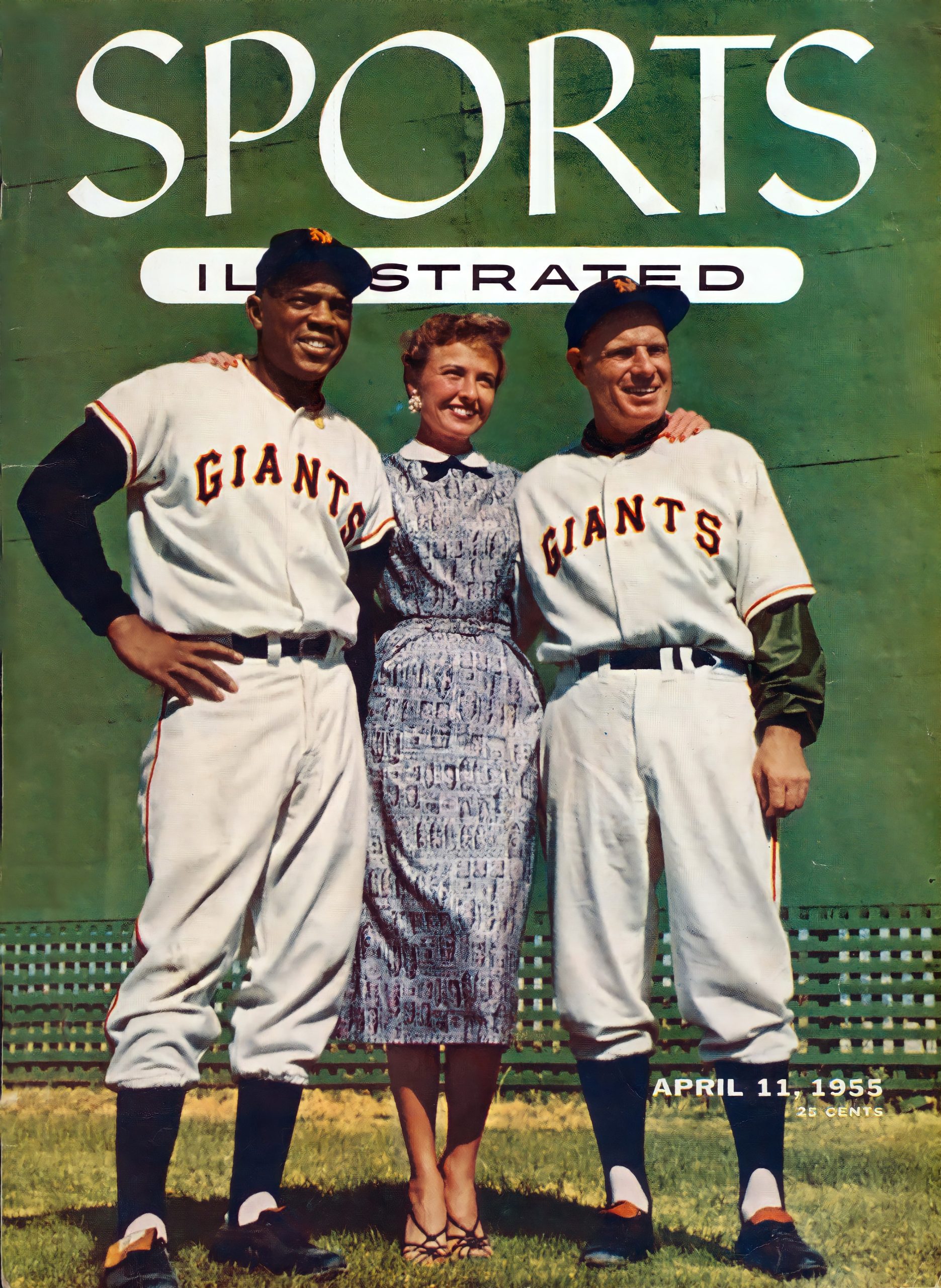

What did Leo Durocher mean to you?

Willie Mays: Leo Durocher was like my father away from home. I first met Leo in Sanford, Florida. We had to play a special game for him. They started me in left field. The first ball was hit, I ran into the wall. He switched me from left to center. I caught the next ball because I had more room. Now he was talking about the Polo Grounds that had the big center field, and I didn’t really understood what he was talking about, but I hit a home run that day. Leo knew what I could do, so it was just a problem of making the transition from the minor league into the majors.

When I went to California I stayed with Leo in his house. His kid, Chris Durocher, was my roommate on the road. Chris would go to the black areas and stay with me. Leo trusted me. He knew that if his kid was going to stay with me, nothing was going to happen to that kid. When we used to eat soul food, he didn’t know what it was. We had black-eyed peas, cornbread, chitlins, and he was used to eating steaks! He goes back and he tells his father, “I had cornbread,” and his father started laughing. So Leo said, “Okay, I’ll give you another $40 a day.” So I made another $40 on top of my meal money. We would get the kid the same stuff. We never game him a steak, the same stuff. He’d go back and tell his father, and he’d come to me, “Haven’t you been feeding my kid?” “Leo, I fed him, what do you want me to do?”

I had such a good time with Leo. I met so many good people in Hollywood. Jeff Chandler used to come to spring training with me, Pat O’Brien, all the movie stars. Leo would have a party for me when I used to go there. All the big stars used to come there: Randolph Scott, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis. So I said, “Leo, why don’t we have a game?” All the stars would come to Arizona and we used to have a game with these stars. We used to have a beautiful outing. So Leo was like my second father away from home.

What happened when they called you to come up to the big leagues?

Willie Mays: I said, “No, I don’t want to come, Leo. I think I’m having a good year, I don’t think I want to come up there.” He said, “Be on the next plane.” That’s the way Leo talked. I didn’t even go back to get my clothes, they had to send for them. My team had to put an apology in the newspaper, because I was doing so well and they was drawing very, very well. The manager apologized for having to bring me up, but he needed me in New York. When they called me I was in a movie house in Sioux City. A message came across the screen: “Willie Mays, report to the box office.” Now I’m saying to myself, “Who knows me in Sioux City? This is my first time here.” I went to the phone there and Leo said, “We’d like to have you in New York. How much can you hit? Can you hit 250?” I said I could walk that. He said, “Okay, you be on the plane the next morning.” That was Leo, he had so much confidence in himself that he put it all into other people.

Weren’t you a little bit nervous?

Willie Mays: Yes. I was crying, I’m telling you. Freddy Fitzsimmons was my first base coach. He used to pitch to me at a lot of batting practices and stuff. I was crying in my locker, and he came in and he saw me, and he tells Leo, “You better go see about your boy. He’s in there crying.” I had played four games and only got one hit. So I’m nervous now. “He’s going to send me back very quickly, because that’s the way they do it in the majors. If you don’t hit, you’re gone.” Leo came out and said to me, “You’re my center fielder. Don’t worry about anything else, just go on home and relax.” I was living at the top of Sugar Hill on 155th Street. All the people I lived with were from Birmingham. I knew all the people. I used to come home at night and see a lot of people out there watching. I’m saying, “Why are all these people out there? They didn’t tell me ’til a year later, that these people were waiting for me to come home. They had to make sure I was in bed by nine o’clock every night, and I didn’t realize that this was happening.

When I got to play stickball in New York, the kids would knock on my window in the morning. Like, if we got a day game or something, I’d be at the ball park at 12 o’clock, they would knock on at nine o’clock. Now I got to eat, I got to get up, I got to go out and play stickball with them for about 20 minutes, and then I had to go to the ball park. And I’m saying to myself, “I’m tired,” but I said, “No, these are kids.” We had no losers there. Everybody had ice cream. So I would take $20 out of my pocket every day, go play, buy the ice cream for all the kids, and they knew that, so they all loved that.

I stayed with a family called Mrs. Ann Goosby. What Mr. Stoneham did for me — which I think a lot of ball clubs should do for young ball players, but they don’t do that anymore — is that they placed me with a family that wanted to take care of me. Made sure that I was at home, made sure that I ate, made sure that I got things that I needed, made sure that everything was fine. If there was a problem, they would call the Giants. The Giants would know the problem before I knew it. So, I think if they can place this young fellow, whoever he may be, with a good family and still be like at home, I think he would be a much, much better ball player. And, that’s what they did for me. I came up in 1951 to 1952 when I went in the service. I couldn’t do nothing. When I had to go downtown — and you know how New York is downtown — I never went by myself. I went with a guy named Forbes. He was the boxing commissioner. And Mr. Stoneham hired this guy — whenever I had to go downtown I had to call him. He would come and pick me up, take me down, buy clothes, or whatever I had to do, bring me back. I couldn’t do nothing by myself. So, I say that they had a lot of stuff invested in me, and they made sure that I didn’t get into no trouble.

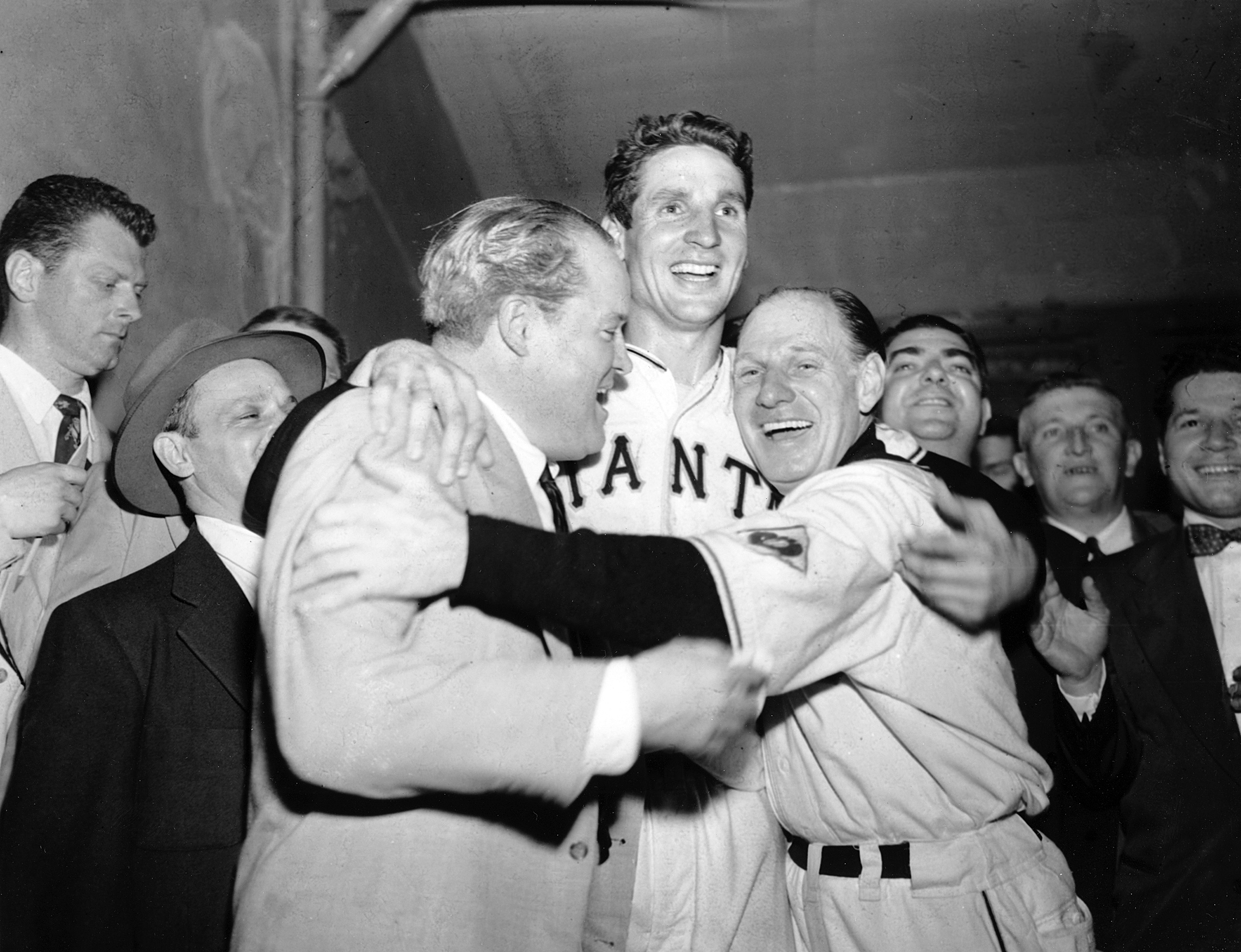

What were you thinking when Bobby Thomson hit the famous “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” to win the pennant for the Giants in 1951?

Willie Mays: I was thinking about the day before. Bobby Thomson had hit a home run off of Ralph Branca in Ebbets Field, so I thought, “They’re not going to pitch to him. They’re going to walk Bobby Thomson, and Leo is going to pinch hit for me.”

That was what I was thinking. I was thinking so hard, when Bobby hit the home run, I was the last guy to get to home plate. I didn’t realize what was happening until everybody started running out.

If you ever see a picture, you’ll see number 24 right in the background of all this pile. Knowing what I know about Leo, I think he would have pinch hit for me, that was my thinking. He said, “No, I would have let you hit.” I said, “No, I don’t think so.” But it didn’t happen, and I was very glad it didn’t, very glad.

Is there any one moment with Leo that sticks out in your mind?

Willie Mays: Do you know anything about pepper? When the guy throws the ball and there’s three or four guys playing around? We used to do that every day in spring training. And fans would come to the ball park like 11 o’clock, just to see that show. It would be three of us. It would be Hank Thomson, Monty Irvin and myself and Leo would be the hitter. And every time we hit, we got to pay five dollars or miss a ball. And he was standing right there. He was standing on top of us. I mean he would hit it hard, and he could never get me, and it would make him so mad because I would catch everything that came close to me. So, one day he hit, and he hit it off the top of my knee. And Mr. Stoneham was watching in the stands over there and I didn’t know this. So, now the guy comes out and he says, “Phone call for Mr. Durocher.” And Mr. Stoneham called Leo and said, “Wait a minute. You may play pepper, and pepper is fine, but if you hurt his knee he can’t play! What am I going to do then?” He says, “I don’t want you doing that.” So now Leo started bunting — hitting the ball easy to me — and then hitting the ball hard to the other two guys. And I’m wondering, “Why is he hitting it so easy to me now?” So he told me later, “I can’t hit it hard to you anymore.” I said, “Well why play pepper then, if you can’t hit it hard?” So, they babied me a little bit. It was fun.

At one point, weren’t you asked to stop hitting home runs?

Willie Mays: That was in 1954. Monte Irvin had got hurt in spring and nobody was driving in runs, and he called me and he says, “I don’t want you to hit home runs anymore.” I said, “What are you talking about? That’s my big thing.”

What was it like playing against your old team, the Giants, after you were traded to the Mets?

Willie Mays: That was one of the hardest things I ever had to go through. I was traded on a Thursday and they didn’t let me play until Sunday, when the Giants came to town. In the seventh or eighth inning I hit a home run.

I get to first base, there’s McCovey, he shakes my hand. Now I got to go to second. Now when I leave him I go to second, there’s Tito, there’s Chris. They both get in my path, for touching second base. When I get to second they said, “Chico, what’s happening with you? Sit here and talk to us for a minute.” I said, “Man, get out of here.” Now my legs started getting wobbly because I’m realizing who I’m playing against. So I get to third, there’s a kid named Al Gallagher, we call him Dirty Al. And he gets there, he throws dirt on me. Now, I get to third and look in the dugout, not in the Mets dugout, in the Giants dugout, and they’re all clapping. So now I said to myself, from third base to home plate, that’s a long ways. And my knees start shaking and I’d never shaken in baseball in my life. So now I started running, but I’m not running. I’m like, “When am I going to get to home plate?” I get to home plate, and Tom Haller is there, and he shakes my hand. Now I began to make a right, like going to the visiting club. I said, “Hold it! Wait a minute!” I thought right away. I had to make the right and I had to go behind the umpire and go over to the Mets dugout. I’m saying to myself, I don’t know how I got round that. A writer asked me the same thing you asked me, “How did it feel?” I couldn’t explain that it was so exciting to do that and have so many guys love you the way they did. I didn’t think I could get through with that.

What’s been the greatest challenge in your life?

Willie Mays: The greatest challenge I think is adjusting to not playing baseball. The reason for that is that I had to come out of baseball and come into the business world, not being a college graduate, not being educated to come into the business world the way I should have. And, instead of people doing things for me, I had to do things for myself. That was scary for me.

I had to go into a place where I’m already at now, Bally’s Casino. I think that was nerve-wracking for me. Now I’m in the business world, I’m meeting business people that I didn’t know about. What saved me was all the business people I met were baseball fans, and they helped me. You take a guy by the name of Mr. Billy Weinberger, who was at Bally’s when I first went to work there. He helped me so much. He says, “Son…” — he used to call me son — “You have to be visible in this business.” We sat down and we talked and he said, “You have to be visible, and you cannot be late. If you take those two things and you put them together, you’ll never have a problem in this business. Because if you’re late, they don’t want to be involved with you. If you’re visible, you’re taking care of the hotel as a whole.” He says, “You have to understand that this is not baseball now.” He was involved with Joe Louis, when he was at Caesar’s in Vegas. He hired me for a 10-year contract. And when I got into the business world, when you say how my life changed, it changed for the best.

I was still working for the Mets, but the commissioner said to me, “You can’t work for the Mets and go down to Atlantic City.” So I had to make a choice. I felt the choice was better in Atlantic City than it was with the Mets, at that particular time. I had so many decisions that I had to make on my own, with help of many friends around me, that my life was kind of scary.

Baseball was like walking through the park. But, coming into the business world, not being educated to the fact that you could deal with all of them, or one-on-one — which I soon found out I could — because just because you’re in the business world doesn’t mean that you’re smarter than anybody that hasn’t been to college. It doesn’t mean that. You can deal with them one-on-one without any problem, and I could because I had been around the world started at age 15, so I knew actually what the business world was all about. I just was maybe a little frightened after coming out of baseball, being this star for so many years and now all of a sudden you’re not the star, and that was frightening to me.

You had to live outside of baseball.

Willie Mays: Yes, I had to learn how to live life outside, but I had so many people help me. I had a guy by the name of Vernon Alden, who was a CEO at First Boston Company in Boston. He was a Dean at Harvard. I used to play in the American Airlines golf tournament, and we were playing golf in Puerto Rico. The question came up, “What will you do when you get out of baseball?” I couldn’t answer that. I’d never been out of baseball. I’d been in baseball since I was 12. That started me thinking. When I got home that night I called him up, I said, “Mr. Alden, could we have lunch? I’d like to really talk about what you asked me.” And he said okay. We became good friends, and he got me three jobs. I was working for the Mets, he got me a job with Colgate-Palmolive on Park Avenue. He got me a job with a company called Ogden Foods, which was in the airports, and they had racetracks. Then he got me another job with Textile down in Charlotte, North Carolina.

So I had all these business people that I’m dealing with. Colgate-Palmolive is a very, very big company, not only here, but across the water. I’m dealing with all these people and he came to me again and he said, “What you have to do is be Willie Mays. They want you to be Willie Mays. All you have to do is be yourself, and you will never have a problem.” And I just started being me. Whatever they ask, I try and do it, to the best of my ability. I didn’t have to do a lot of speaking, because they had professional speakers for that. Every company liked to show off their products and different things, and they knew their product.

I’m a very lucky guy. I had so many people help me over the years that I never had many problems. If I had a problem, I could sit down with someone and they would explain the problem to me, and the problem become like a baseball game. You’re at home plate now, how do you get to first? How do you get to second? How do you get to third? When you get back to home, your problem is solved. That’s the way I view the business world, I view it as a baseball game. Once you start thinking the way you’ve been taught to think over so many years, you have no problems.

I don’t care what the problem is. If you’re a writer, what do you write about? First you write about what you know. That’s exactly what I’m saying. I was a baseball player, I taught baseball, and all of a sudden I was in the business world. Now I used the baseball world to talk about their product. Not too much, just enough to keep going. Just be yourself and you’ll never have a problem. That’s what I did.

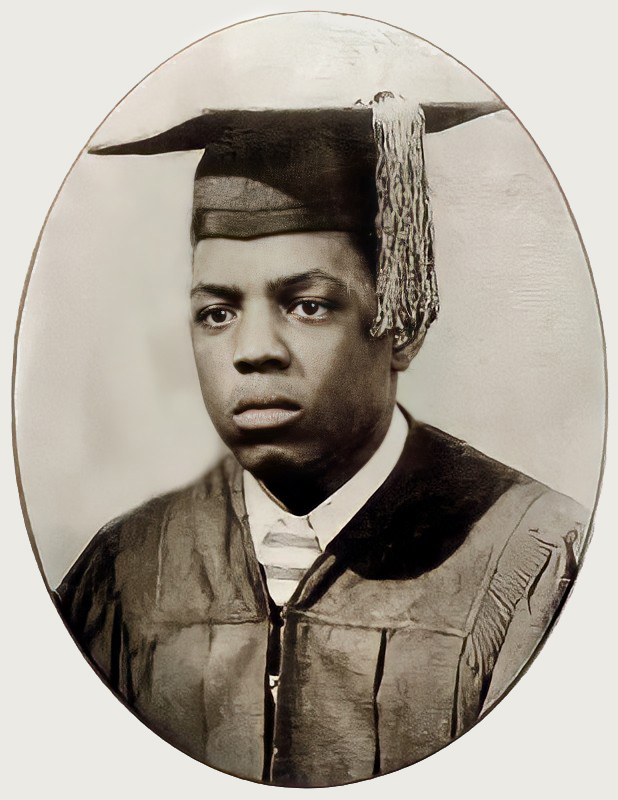

Why was it important to graduate from high school?

Willie Mays: My father said to me, “You need a piece of paper to go into a door sometimes.” I didn’t understand about résumés, but when you write a résumé you have to put down things that people want to know about. Did you finish high school? Did you finish college? He said, “You have to have that piece of paper.” I didn’t play sports in high school my last two years. In 11th and 12th grade they wouldn’t let me play because I was playing professional ball. It was important that I get that piece of paper.

To tell you the truth, I didn’t get the paper because, if you remember, I left at my prom and went to play with Trenton, so I didn’t get the paper. Somebody had to pick it up for me because I was playing in Trenton. My father kept it. It was very important to my father for me to receive that piece of paper.

You went to class.

Willie Mays: Yes, I went to class every day. In my hometown, where were you going to go? Everybody was in school. If they saw you walking down the street somewhere by yourself and you’re not in school, your family would know about it. My father would know if I didn’t go to school. The principal would check on you every day. They had a patrol. The truant officer would come by your house to find out why you’re not in school, so that was never a problem there. You might be able to get out earlier now and then, but you had to check in. They called roll and you had to answer every day. You might be able to get off of school to practice football, or whatever, but you had to be there at all times.

Were there any books that inspired you?

Willie Mays: History. I remember everything about blacks, things in history that nobody gave the blacks credit for. I began to pick up a lot of things out of these history books. I liked math, because I would begin to deal in money. I began to understand how to count, very quickly. I’m talking about fractions, and how to divide. Certain things would pick up my eye very quickly. I got a really good education for what I needed in the South.

Were you looked up to by other students?

Willie Mays: I didn’t say I was that smart, I said I went to class and I enjoyed what I was doing. We had a kid in our school who went to college at 14. I thought that was too young for him to go to college. He was out of college at 18 and into another job. Now that’s too fast. Where was his childhood going? I don’t think I was looked up to that way. I was looked up to as an athlete. There were a lot of smart kids in my class, a lot of them.

But you were looked up to.

Willie Mays: Very much so. I was the best athlete in the school. That’s why the principal wanted me to play high school ball and not professional ball. I said, “No, I want to play professional ball.”

Do you remember wanting to be anything but a ballplayer?

Willie Mays: In the South you only had certain things you could do. If you didn’t play a sport, what could we do? When baseball season was over, we played basketball till 11 or 12 o’clock at night. Baseball season, we played ’til late afternoon. Football we played — especially in the summer — you could play up to around eight — nine o’clock. So we played every day. I used to play on the high school team, and then go play sandlot ball on Sundays, without any shoulder pads and things. We didn’t have no shoes, I used to kick barefooted. You know, 50 — 60 yards. I used to kick the ball hard, you know. I didn’t kick-off too much without shoes. I used to kick it, but on the side — spiral.

Did you imagine you’d achieve this greatness?

Willie Mays: I think if you start thinking that way, you don’t achieve anything. You cannot look ahead and say, “This is what I’m going to be in 20 or 30 years.” It doesn’t work that way. You can have goals for 20 or 30 years. My goal was to get into the Hall of Fame. Once you get into the Hall of Fame, you know you did something good in baseball. That was my goal. But to sit down and say, at age 15, that in 20 or 30 years you’re going to be in the Hall of Fame? No, I don’t think you can think that far ahead. If you’re thinking so far ahead, you forget to do things.

Do sports heroes have a responsibility to young people?

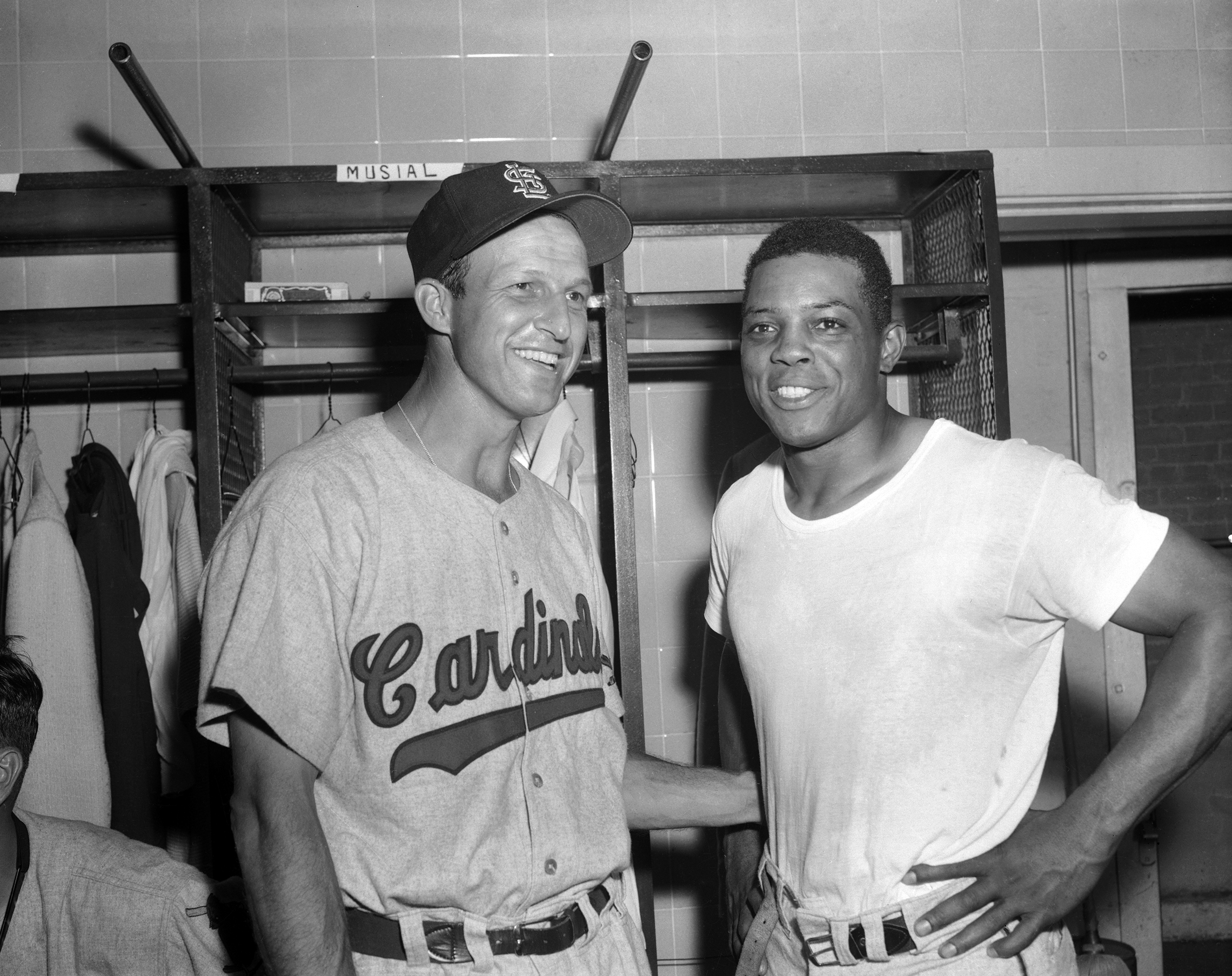

Willie Mays: No. I think the responsibility comes from your families, just like mine. I had guys I admired: Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and later Jackie Robinson, but your mother and father are the ones that have got to teach you right from wrong. You can admire whoever you want to admire, but that person is not going to teach you. You can try to emulate whatever he does, but your mother and father are going to be there with you every day, day in and day out. They are your heroes, I feel. My father was my hero.

What one thing would you say to young people today?

Willie Mays: I would say the main thing in any young kid’s life is education. Even if a guy is prejudiced, he can be educated to understand why he is prejudiced. Education plays a great role in all life, whether you’re black or white. You’ve got to go to high school, you’ve got to go to college. When you come out of college or high school, you can play sports. If you ever get hurt, they can’t take that brain away from you, you’ve got that. You can sit in a wheelchair and still operate a machine or a computer, if you’re educated enough to do all that. Let’s turn that around. If I’m just playing sports and I get hurt, what do I do? I can’t run a machine, I can’t type, I can’t go out and talk to kids. I’m not educated enough to do that. So education is very, very important as far as I’m concerned.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

Willie Mays: My American Dream, speaking for myself now, starting back as a kid, looking at the progress that we have made as far as blacks are concerned, starting with Jackie Robinson, Joe Louis, and moving up. Having a black kid like myself move into sports, be the number one guy in sports. Having Dr. King come in and turn part of the world around from wrong to right. Being able to come from Birmingham and live the way I do, not knowing that I would ever have a home the way I have. Not knowing that I would ever be in a position to help other people the way I want to help them.

The American Dream can come in many different ways for many different people. It doesn’t have to come in the way they explain it to you. Now, the American Dream can come if a guy hits the lottery. Who in the world thought he would hit a lottery? That’s the American Dream for him. But I look at it from day one, moving up the ladder, and moving up the ladder. Now you get to the top of the ladder and you have to look back. How did you get to that ladder? To me, that’s the American Dream. And going through the American Dream you have to go through stages. That’s what I’m saying about education. Hopefully, the kids can have their own American Dream. Then they can look back and say, “I’m educated enough to understand about what he was trying to tell us. Now I can understand a little bit more about it.” The American Dream is a very powerful word. That’s very powerful, I think.

Thank you so much for speaking with us today.