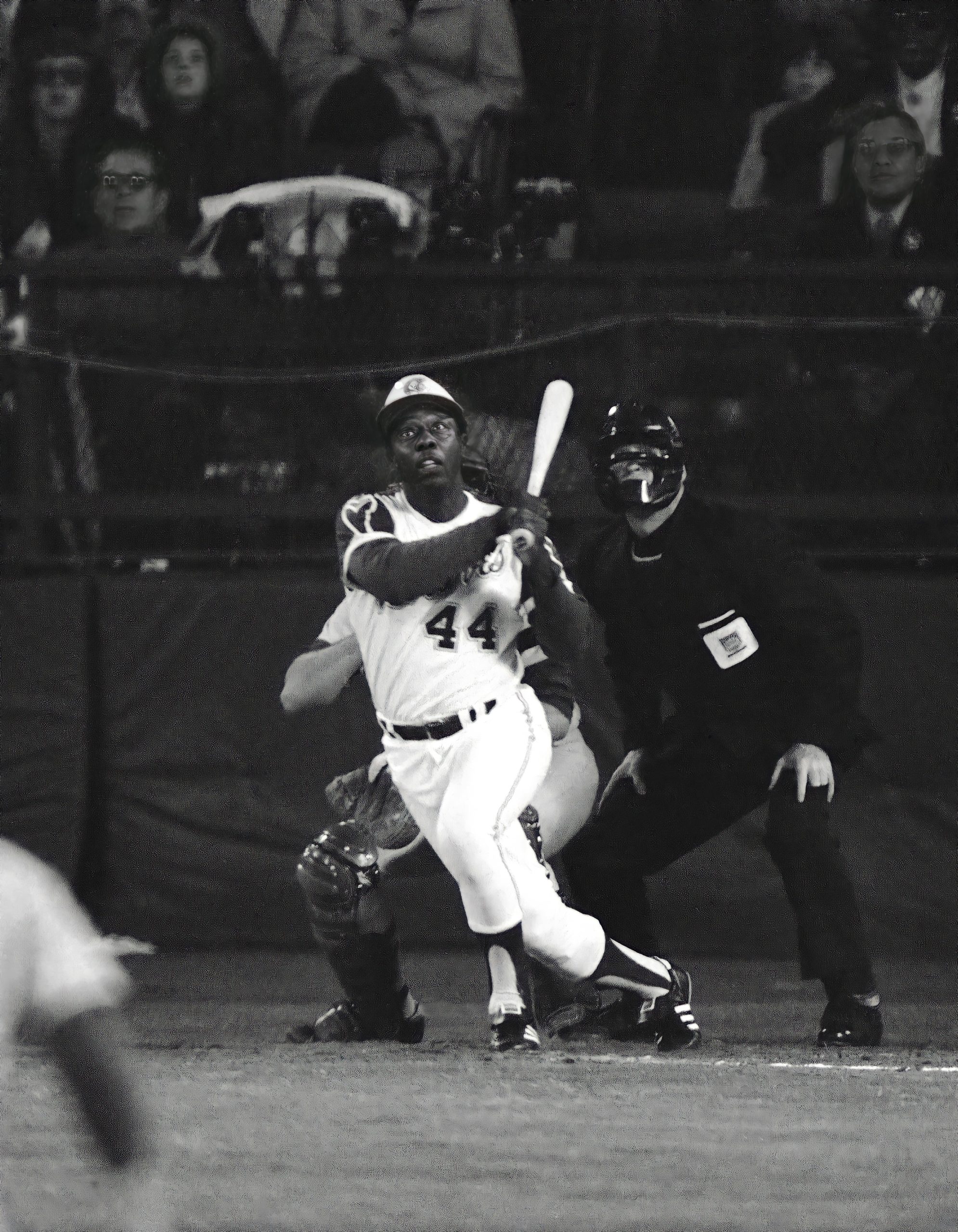

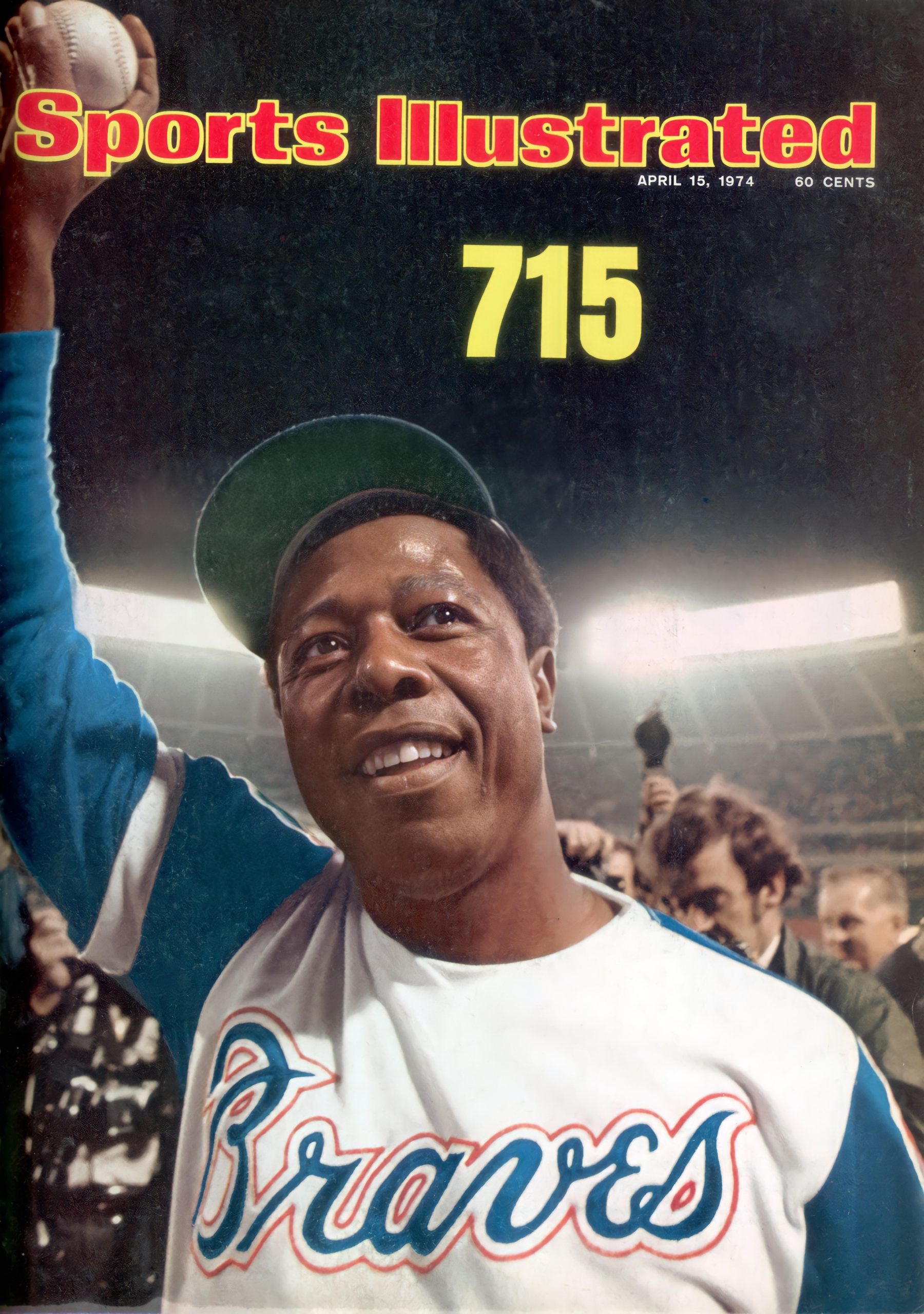

Your teammate Darrell Evans says he was on deck when you tied the record in Cincinnati, and when you came out of the dugout you said, “I’m going to do it right now.” And he says he was on deck before you broke the record in Atlanta, and you said the same thing. You didn’t say it the first time you batted that night, when Downing walked you, but you said it before you hit number 715. How did you have the confidence?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know what I said. I’m glad he said that. Something probably came out of my mouth that didn’t sound right! I probably was joking with him. It’s kind of hard. They talk about Babe Ruth pointing his finger and hitting that ball in a certain spot. That doesn’t happen in baseball. Sometime you can walk up and say, “Oh I feel like I’m going to hit a home run,” and you might hit it. Sometimes you might say “I just feel like tonight I’m going to have a great night,” and you might have a great night. But it’s hard to predict that you’re going to hit a home run when you want to!

It sounds like you had a lot of confidence, and maybe that’s the secret. You say that when you got home you got down on your knees and prayed. Are you a religious person?

Hank Aaron: Not really. I wished I was, much more than I am. But I do go to church. I believe in God. I’m not as religious as I should be. But I believe that there is somebody that is much greater than I am.

Your achievements have inspired a lot of people. What lesson would you like young people to learn from your career?

Hank Aaron: I would like for young people — especially African American kids that’s growing up — I want them to understand that there is no shortcut in life. I want them to understand that if you’re looking for shortcuts, then life is not going to treat you very well. You got to take one step at a time. You got to do it right. I want them to understand that regardless to how bad things may be one day, that you can wake up tomorrow, and things are going to be a whole lot better tomorrow. I would like for them to understand that. And I would like for them to understand that that’s the road that I took. My daddy insisted — my parents insisted — upon me doing that, rather than trying to make something quick happen, you’re not going to make it.

How did they feel when you told them you wanted to run off and join a baseball team?

Hank Aaron: I think my mother had some reservations about it, but my father wanted me to go. He said, “Go and give it a try. If you fail, come back. I got a job for you!” But my mother, she didn’t want me to go. She wanted me to stay home. I was more of a mother’s boy than anybody.

How many kids were there in your family?

Hank Aaron: There were eight of us.

And they didn’t want one of you leaving?

Hank Aaron: No, she didn’t want any of us leaving. She wanted all of us to be around.

In the 1940s, Mobile, Alabama was not the safest place for a black kid to pursue equality. Tell us about the life of young Hank Aaron. Were you aware of segregation, and if so, how did you feel about it?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know that I was aware of it, but I was conscious of who I was. I don’t know that I was ever put in a position where I had to go over here to drink water, or go over here to head to the bathroom. Of course, I grew up in the country…

I actually grew up in a little place called Toulminville, Alabama. It’s a little country town. There were no roads. I mean just little farm roads. And I can remember many nights, many nights my brother and I would be out playing baseball, just throwing the ball, because we didn’t have any lights. But in the dark of the night, she would tell all of us to come in the house. And I would say, “For what?” She said, “Just come in the house and get under the bed.” I said, “For what?” She said, “Just get under the bed.” And then about ten minutes later we’d have the Ku Klux Klan coming through, intimidating, throwing firebombs and things like that. And that’s what really kind of set you all apart, and said, just because your skin is a little different, then they were going to treat you a little different.

Horrible. Is it true that you used to make your own baseballs?

Hank Aaron: Believe it or not, I used to make them out of rag dolls. My parents couldn’t afford to buy a bat, they couldn’t afford to buy a ball, and so actually we did everything we could in order to pretend like we was playing baseball. We would take rags and wrap them up tight and throw to each other. Or we would take pop tops, like soda tops, and throw, and try to hit balls with a broomstick. We did anything that we could in order to pretend like we were playing baseball in a big league camp.

Had you seen baseball? How did you know about it?

Hank Aaron: Actually I heard about it, sleeping in bed at night. The Mobile Bears, which were the farm club of the Brooklyn Dodgers, were in Mobile, and I would hear this friend of mine — when I say a friend, it was someone I knew next door — would have his radio on, and he would have the radio on to the Mobile Bears, and I could listen to them. That’s how I knew about baseball. That’s how I kept up with it. I didn’t have enough money to go to the game, so I had to listen to it.

You could hear the crack of the bat, and the crowd cheering?

Hank Aaron: I could hear that. I remember a player by the name of George “Shotgun” Shuba who played a few years with the Brooklyn Dodgers. I remember all of those players. That was the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Double A team, and they used to take a lot of the players off of that team and bring them to the big leagues.

You batted cross-handed as a young player. Why is that, and when did you stop?

Hank Aaron: Because nobody taught me any different. Cross-handed means I was doing everything backwards. I was taking my left hand and putting it on top of my right hand and trying to swing this way instead of swinging that way. Nobody ever taught me any different, and I was doing pretty well, so I just continued to do things the wrong way!

Is there a wrong way and a right way?

Hank Aaron: Yes, that was definitely a wrong way. I don’t think you can go very far by stacking your hand this way, because the higher you get in baseball the more pitchers are going to be able to jam you with certain pitches. You wouldn’t be able to get around on inside pitches.

In the 1940s, it was against the law for black and white kids to play baseball together in Alabama. Could you tell us about your memories of Carver Park in Mobile, and why it was important in your life?

Hank Aaron: Carver Park was centrally located in the black section. I never played with a white player until I got to Eau Claire, to be honest with you. When I got to Eau Claire — and Eau Claire was the farm club of the Braves, as a Class C ball club — that was the first time I ever played with white players. Before then I played in the Negro League, and before that I played in Carver Park, which was all black. So I never had the experience of playing with white players until I got into professional baseball.

Jackie Robinson came to Mobile in 1948, when you were 14 years old. Could you tell us about that experience? What did Jackie Robinson say to you?

Hank Aaron: Actually, he said nothing to me, because I was scared! But I remember when he came there with the Dodgers, and I’m almost sure he spoke at one of the grocery stores there. I remember skipping school — which I did often — skipping school to go hear him talk. He was just talking about his experience in baseball, and what those of us who wanted to pursue baseball should be looking out for. He was delivering the same type of message that I deliver really. I tried to talk about shortcuts, he tried to talk about shortcuts.

The Brooklyn Dodgers held a tryout camp in Mobile for black players in the summer of 1951. What happened there?

Hank Aaron: Well I was — you can say I was a little bit skinny. Weighed about… I guess I weighed about a hundred and… I might have weight 110 pounds, you know, and they had other players there that weighed more than me and had better… could hit the ball a little bit further, and I didn’t get a fair shake. They said, well, when I got to the camp to workout, they just thought I was too small, and they just brushed me aside, you know, and said, “You come back later on.”

But you weren’t crushed by that experience. You had the determination to come back.

Hank Aaron: I was not crushed. I was a little disappointed, of course. I felt like my mark was not made. I had done well, but the other players who got a chance over me had done much better than I had. I was living in an area where I didn’t get any notoriety at all. I mean I was playing baseball and doing well, but these other kids were playing in “Down the Bay,” as they call it, and they were getting a little bit more notoriety than I was.

A little later, you received a contract with the Indianapolis Clowns, and were asked to meet the team for spring training in North Carolina. You were only 18 years old. Were you frightened to leave home? Were you nervous when you got on that train?

Hank Aaron: I was frightened and nervous! I don’t really know, I really don’t know how I made it. I remember my oldest sister, who is no longer with us, and my mother carrying me to — when I say carrying me, they walked with me — to the train station, put me on the train, and I had a little bag with one pair of pants, and my mother had fixed me two sandwiches, and I had — I think it was two dollars in my pocket. And she told me this is all she had. And my sister told me — she kissed me — and she said, “Just do the best you can.”

That was a big step to take.

Hank Aaron: So I got on the train. Yes, I was nervous, scared, and didn’t know where I was going really. I’d never been on the train before in my life. I think that train carried me to almost to Durham. Somewhere in tobacco country, I remember that. I remember I had to get off of the train and transfer to another one, and I had to ask five people where I needed to go, because I didn’t know where to go. To answer your question, I was really scared.

When you started out, only six of the 16 Major League Baseball teams had broken the color barrier. The Negro National League is only a memory now. Tell us about the importance of the Negro Leagues to players like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige.

Hank Aaron: It was probably one of the greatest minor leagues that you could have. I came from there, Willie came from there, Ernie Banks came from there, Gene Baker came from there, and Jackie Robinson, Campanella, Don Newcombe. It was a feeding ground.

When you talk about the Negro League, it was a feeding ground for the major leagues. I don’t know that I would have been in the big leagues if I had not had the experience of playing in the Negro League. Some people say, “Well, what class of ball would you put it at?” And I would say that the Negro League probably was, I would say a high A ball. I had the experience of playing in that league for — I don’t know — a couple of months. But so many other players — Ernie Banks played there, and he went from there to the major leagues. Gene Baker did the same thing. Jackie Robinson I think stayed in the minor leagues for a year-and-a-half. Campanella, Don Newcombe, all these guys came through that league to get to the big leagues. And they were polished. They knew how to play the game. I knew, I learned an awful lot from playing in that league, simply because of the fact I played with the older players, players that knew how to play the game, and all of those things rubbed off on me. I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and how I did, when the situation came about.

Did it scare you to leave an environment that you felt comfortable in, all black players, and move into a situation that you did not know?

Hank Aaron: Oh yes, it scared me. I didn’t know what to expect. When I left the Negro League and went to Eau Claire to play with the Eau Claire Bears, I had absolutely no earthly idea where I was going, what I was going to do, where I was going to. I don’t know. I didn’t know how to accept it, really. But when I got there, Eau Claire, and put my uniform on, and got on the baseball field, and when I walked out and I got my first base hit, the fans kind of took to me, really, and it was the greatest experience that I had ever had. I played a half year at Eau Claire and a full year at Jacksonville. I say I had more fun at Eau Claire than I had at Jacksonville.

Was there one black face in the crowd as you looked out and they were cheering for you there?

Hank Aaron: Didn’t see a one. I don’t know. I think I only saw one black face in the whole city of Eau Claire.

But they loved you?

Hank Aaron: The fans? I got along with the fans well. In fact, I had a family that always talked to me and said, “Whenever you want to come by and have dinner, come by our house.” And I used to go by there quite often and have dinner with them. Yes.

It was a scout named Dewey Griggs of the Boston Braves who discovered you, wasn’t it?

Hank Aaron: Dewey was a scout for the — then Boston — Braves. Of course Milwaukee turned up later. The thing about Dewey Griggs is that he signed Henry Aaron, he signed Johnny Logan, he signed Frank Torre, Joe Torre, Don McMahon. All of these players that he signed got to the big leagues. He was one of their super scouts. How did he manage to pick me? I still feel grateful and thankful, but I came in there too. He signed me, and he signed one or two other black players.

He saw real talent when he saw you.

Hank Aaron: Well thank you.

A few years before, the Braves almost signed another player, Willie Mays from the Birmingham Black Barons, but instead he signed with the New York Giants. You almost signed with the Giants too.

Hank Aaron: I did.

How did you decide what to do?

Hank Aaron: Only because of dollars. Not big dollars…

I think it was 200 dollars or 100 dollars more that the Braves was giving me than the Giants. We almost were teammates, Yet I look back, I’m so thankful and grateful. I would have loved to have had a career with Willie — Willie and I in the outfield — but playing in Milwaukee was the greatest experience I ever had in my life. Really, it was so rewarding to me, because when I got to the big leagues I made a lot of mistakes, a lot of mistakes. Bunting with runners on third base, and running when I shouldn’t have been running. And the fans never booed me. Never, never once booed me. So I just am grateful that I had a chance to play in Milwaukee.

That’s great to hear. When you reported to the Braves you had your first plane ride, the one to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and you received a signing bonus. Was that a big deal?

Hank Aaron: And I didn’t get one nickel of the signing bonus!

Who got it?

Hank Aaron: I think Sid Pollock, who owned the Indianapolis Clowns at the time, got all that. I was under contract with him. And the bonus, whatever it was — 5,000, 10,000 — it was a bonus that each step that I went, from Class A to Double A, they would give him so much money, so much of the 10,000 dollars. But I didn’t get anything. I didn’t get one nickel. The only thing that I got out of the whole deal was a cardboard suitcase, back when they made cardboard cases. I remember going to Eau Claire when it was raining, and when I got off the plane with my cardboard suitcase, I didn’t have anything in my hand but a handle!

Did they give white players any more than that?

Hank Aaron: Oh, back then you didn’t get bonuses. They probably got a little more than black players, of course. No question, but I don’t think that the money was very plentiful.

In 1953 you played in Jacksonville for a Braves farm club in the old “Sally” (South Atlantic) League. You broke the color line there. What are your memories of those days? How were you received in Jacksonville?

Hank Aaron: It was hard, it was hard, it was very, very hard, but it was typical of a Southern city. I had problems all over the league. I played there with Felix Mantilla, who was a Puerto Rican, and another player named Horace Garner, who was much older than the two of us, and we never stayed at the hotel. We had to stay at private homes. We didn’t stay at hotels on the road, we had to stay at private homes. So we didn’t enjoy the luxury of playing like some of the white players. But it was a great time for me. I led the league, I say. I always tell people I led the league in everything but hotel accommodation! But I had a great year. I led the league in everything. Batting, running, runs batted in, and so forth. That was a stepping stone for me, going from Class A to the big leagues.

When your team clinched the Sally League pennant, there was a party to celebrate. Could you and the other black players go to that party?

Hank Aaron: No, we didn’t. None of us. You know we were still playing in the South. We couldn’t enjoy anything that some of the white players would make. In fact, when we played in the Sally League, the bus would drive to, say like to Montgomery, and they would let the white players off at the hotel, and they would take us to… we would have to go out, out off the bus and get the cab, and find a cab to go to the hotel — not the hotel but the rooming house — where we stayed at.

Can you remember what that felt like?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know how I felt really. It was hurting, very degrading. It felt like you were not part of the team. It felt like you were a second class citizen. But you felt like you had to do it in order to make things easier for somebody coming behind you. Even the most humbling situation, you knew that whatever you did, that tomorrow things were going to be better.

Did you have any friends among the white players on the team? Did any of them express disappointment about the kind of things you were having to endure, as a player who just happened to be a different color?

Hank Aaron: I did. I had a very good friend named Joe Andrews who lived in Boston, Massachusetts. He was probably one of the first bonus players that ever played. Joe and I were very good friends. He’s no longer here. He’s deceased, but he and I were very good friends. He and I got along very, very well. In fact, he was the only one that, no matter what we did, he would come and be by our side. He was great. In fact, even after I got to the big leagues and he opened up an automobile place, I used to go to Boston, Massachusetts quite often to visit him. He was a very good friend of mine.

In 1954, America met the 20-year-old Henry Aaron. The Civil Rights Movement was taking off at the same time. In effect, sports stars like Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis had already led the way. But how did you feel about what was going on in the country, when you saw things on television, with people being dragged from lunch counters…

Hank Aaron: And fire hoses and things like that. It certainly was a sad moment. The thing that, I think, that all of us — in fact, in talking to Don Newcombe and some of the other black ball players — was that, I think Dr. King had said that he wanted us to keep things like they were, because we were playing baseball and we were integrating situations in other areas. And we were doing it a little bit more — they were a little bit more peaceful with us than they were with just the average black person in the South. We looked at it, and some of us, including myself, wanted to take time out to go and be part of the march, and be part of whatever Dr. King and some of the other civil rights leaders were doing. We talked it over, and we decided that the best thing is to sit — is to continue to do baseball. Because things were — we were seeing a little progress in baseball. I know when I first started in Jacksonville, blacks and whites could not mingle together. And then at the end of the season, they were starting to go together, and shake hands, because it was for one thing, and that was to try to win a championship. So all these things, we saw it was hurting, when you look at TV and see you things like that and you’re not part of it, but yet you feel like you — and I mean “you,” myself — you were making progress as far as trying to help bring equality yourself.

You did make a difference. You had a chance to play in Mobile, and share the field with Jackie Robinson and the other Dodgers. What was that like?

Hank Aaron: Probably, other than hitting a home run to clinch the pennant for the Braves, one of the greatest moments I ever had was playing in my home town against the Brooklyn Dodgers. And there was Jackie Robinson. All of us were right there in Mobile.

How did your family feel about it?

Hank Aaron: My family felt good. I had a good day. I think I had two or three hits, so they felt very well. My mama would say, “My boy has come a long way. And he has made it a little bit comfortable for me!”

In your first year with the Milwaukee Braves, you were filling in for the legendary Bobby Thomson, who was injured. You’ve said, “I started to get ready for every game the minute I woke up.” How important is that kind of preparation?

Hank Aaron: My first year in the big leagues, I knew I had had a great year in the minor leagues. I mean a great season. Today, if a kid have that kind of year in the minor leagues, he would come up and sign a 15-year contract. I had a great year, but I knew, back then, that regardless to what kind of year that I had — and this didn’t only refer to me, it referred to every player, because there was so many good ball players back then — I knew that I was probably going back to the minor leagues. No matter what happened, I knew that if I had the greatest spring training — and I did — but I was ticketed back to the minor leagues I was going to Triple A, because the Braves had made a very big trade, they had traded for Bobby Thomson, and Bobby Thomson was going to be the left fielder. He was going to play left field, and I was not going to play. So they was sending me back to the minor leagues to get more experience. And as fate would have it — not anything that I had anything to do with — Bobby Thomson broke his ankle in St. Petersburg. I had played a year — half a year, rather — in Puerto Rico. Charlie Grimm, I don’t think he really wanted to keep me, but I think between the management and the general manager, they persuaded him to keep me on the team, and he just did. To do that, he wanted to bring in somebody with a little bit more experience, somebody who had played in the major leagues. At least, I didn’t have anything to do with it, but somebody convinced him to keep me on the team.

You have said, “To me, hitting is a matter of knowing where the ball was going to be and when.” You felt your strengths were your strong arms, your wrists, and your eyesight. You focused on the pitcher’s body too. There are more than 100 books on hitting a baseball. You can download hitting apps on your phone, even. Everybody has got some ideas, but it worked for you. So what’s the secret?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know that it was a secret. I just concentrate on everything I had to do. Baseball was my livelihood. I thought about it, I studied it. I practiced as much as I possibly could. Where some players practice during the day, during the game, I practiced all — I would go out and do things that they would never dream about doing. And I can tell you what pitchers — in what situation they want to throw a certain pitch to me. So I knew that. And I knew it only because I studied the pitchers a little bit more than just the average did.

We’ve read that you didn’t even go to movies during the day because you wanted to keep your eyes adjusted to the night game lights.

Hank Aaron: I didn’t go to the movies. I stayed in. If I would travel from, say from Milwaukee to Philadelphia, and that evening we had a night game, and we would get in in the morning or something, I would never go out of the hotel until the game would start. Because I just felt like I needed to stay, and study and study, and just keep my eyes. Rather than going out and looking at bright sunshine, wait until the night, and it would be accustomed to being — because I would be in the dark!

Where did these observations and all this insight come from?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know. I think it just came from the Good Lord, really. I don’t know. My father always taught me, if you want something bad enough, you’ve got to learn how to go out and do something special in order to accomplish and get it. I just felt that I had the ability to play baseball, that was given to me by God, but I had to apply my own intuition into it in order to make myself a little bit better. In order for me to do that, then I had to do some things that ordinarily another player would not do. I had to make sure that if a pitcher was out there on the mound, that I knew exactly what his weakness was, because he had already studied mine. I felt like I need to be ahead of him at all times, and that’s what happened.

So you saved your eyes for the night games. Cal Ripken told us he had a difficult time seeing the ball until the later innings. Did you ever have that problem?

Hank Aaron: No, I never had a problem. My eyesight has always been pretty good.

You must have played in Washington when it was still segregated. Do you remember trying to go to a restaurant while you were there?

Hank Aaron: That was when I played in the Negro League. We played one game in Washington and were going to play a doubleheader in Baltimore. So we had to eat in a restaurant in Washington. So they fed us, and then they broke all the dishes, yes.

They broke the dishes?

Hank Aaron: They broke the dishes.

How did you know?

Hank Aaron: We could hear them breaking them up. Carrying them back in the back, breaking them up. We could hear that.

Incredible. In 1957, it was a magical year for you and the Milwaukee Braves. You must have dreamed of a moment like this, an eleventh inning home run to beat the Cardinals and win the pennant. Your teammates carried you off the field. Why were those moments such a treasure to you?

Hank Aaron: Here, a little black kid from Mobile, Alabama who has hit a home run to clinch a pennant for the Milwaukee Braves and was carried off the field. And yet, about a mile… No, not a mile! What am I talking about? I would say, in the other part of the country, not the city. In Little Rock — I’m going to get it right — where a black kid was trying to go to school and had to be escorted by marshals into a school. So that was the thing that was so ironic about that. Here I was, a black kid that hit the home run and was carried off the field by white teammates on their shoulders. And yet a little black — what, two, three, five, six, or seven years old, 12 years old — was escorted into school by marshals. So that was the thing that was so ironic about that. The home run was great, but yet it still was part of a… You think about it and you say, “Although this is great for baseball, but other parts of the country, it’s sickening when you see things like this happening.”

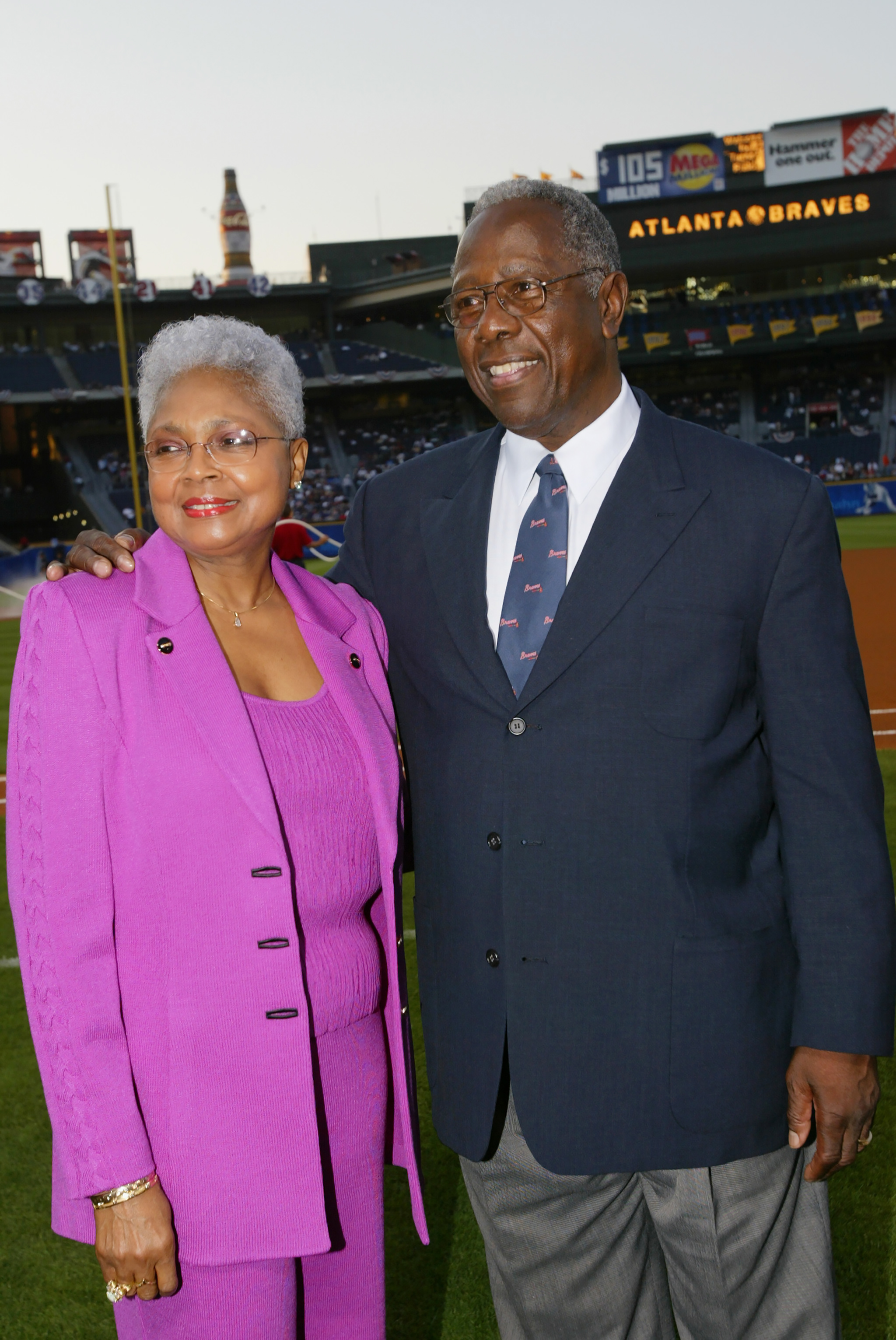

When the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1965, we’ve heard that you felt like you would be on trial there, and that you needed a decisive way to win over white people. Do you feel that move to Atlanta worked for you? Some people say you had a hand in bringing Atlanta into the modern era.

Hank Aaron: Well, that part I don’t know! Playing in Milwaukee for so long, I felt like this would never happen in the South. In order for the people to realize that I was as much a part of the team as anybody else, I needed to win them over by hitting home runs, by doing something that they would enjoy. I felt like hitting home runs would do it, and it did. I don’t know how many home runs I hit the first year — I think 55 or 40, somewhere thereabouts — but I did, and it won a lot of fans.

What did you learn from Satchel Paige and the other old-timers?

Hank Aaron: Satchel and I — he was before my time of course — but I happened to play with him the last part of his career, thanks to Bill Bartholomew, who was the Chairman of the Board and owned the ball club at the time. He brought him back so he could be eligible to collect his pension. I got to know him pretty well. Very smart, very wise man, very smart. Just was saddened that he didn’t play in the big leagues a lot longer than he could have, simply because of the color of his skin. But he talked an awful lot about — he did a lot of bragging, bragging, bragging and he could brag, because from what I gather from other black ball players who played with him, they say he was probably one of the greatest pitchers that ever toed the rubber. Very, very, very knowledgeable of the game. Even at his age, and I think Satchel must have been somewhere close to the last year — I’m talking about the year that I played with him — that he came back to the league, he must have been in his 70s. And at that time — and I’m not exaggerating, Satchel could still throw the ball very, very well — and for someone to be out there catching the ball and throwing it as well as he did, that tells me one thing. If he had been given the opportunity to play like everybody else, he’d have probably did wonders.

When the Braves moved to Atlanta in 1965, we’ve heard that you felt like you would be on trial there, and that you needed a decisive way to win over white people. Do you feel that move to Atlanta worked for you? Some people say you had a hand in bringing Atlanta into the modern era.

Hank Aaron: Well, that part I don’t know! Playing in Milwaukee for so long, I felt like this would never happen in the South. In order for the people to realize that I was as much a part of the team as anybody else, I needed to win them over by hitting home runs, by doing something that they would enjoy. I felt like hitting home runs would do it, and it did. I don’t know how many home runs I hit the first year — I think 55 or 40, somewhere thereabouts — but I did, and it won a lot of fans.

What did you learn from Satchel Paige and the other old-timers?

Hank Aaron: I’m so thankful that the one great person who was there, the person that I admired so much, was Stan Musial. Stan came, and he didn’t have to be there. Nobody paid his way. He paid his own way to come there, and he come there to see me get my 3,000th base hit, and that was the greatest. That was one of the greatest thrills I’ve had in my lifetime in baseball. Later on in my career, Stan and I, Joe Torre, Mel Allen, and Harmon Killebrew visit Vietnam. We stayed over there for three-and-a-half weeks or more, all of us, and Stan and I was roommates. I mean, he and I was roommates. It’s a funny thing. I tell this story because Stan, somebody had given him — or he had bought — a Kodak camera, one of these high, high cameras. Nobody knew how to use it but Stan. I don’t think Stan knew how to use it! And I remember going on these wild cases, and Stan would be clicking pictures and taking all kinds of pictures. And I told Stan, I said, “Stan, now you make sure when you get a copy of this, I want to get a copy of these pictures.” And the next time I saw Stan Musial, I said, “Stan, did you get a copy?” He said, “No, I didn’t get anything but the floorboard of a helicopter!” But that was Stan. He was such a wonderful person. Such a great ball player, but just a wonderful human being.

It’s so beautiful that that’s what you remember about that 3,000th hit, that he was sitting there.

Hank Aaron: He came out on the field and shook my hand.

Was he your hero?

Hank Aaron: Oh, yes. Stan was always a very good friend, not only one of my heroes. Along with Jackie Robinson and some of the great black ball players, but Stan was right in the middle of them. I don’t know what you would call him, he was just Stan Musial.

“Stan the Man.”

Hank Aaron: “Stan the Man.” He was a great hitter, a great ball player. I’ll tell you another story, and this is a true story. I tell this often, but I don’t know whether people believe it or not.

My first All-Star Game in Milwaukee, Stan and I was on the bench along with Willie, We eventually won the game in extra innings. But I remember Stan Musial, Stan hit the home run to win the pennant — I mean to win that game. I remember Stan walking up and down on the dugout, and he said, “Well, boys. They don’t pay us enough money to play extra. I might as well go up here and hit a home run.” And sure enough, goes up and hits a home run, out of the ballpark.

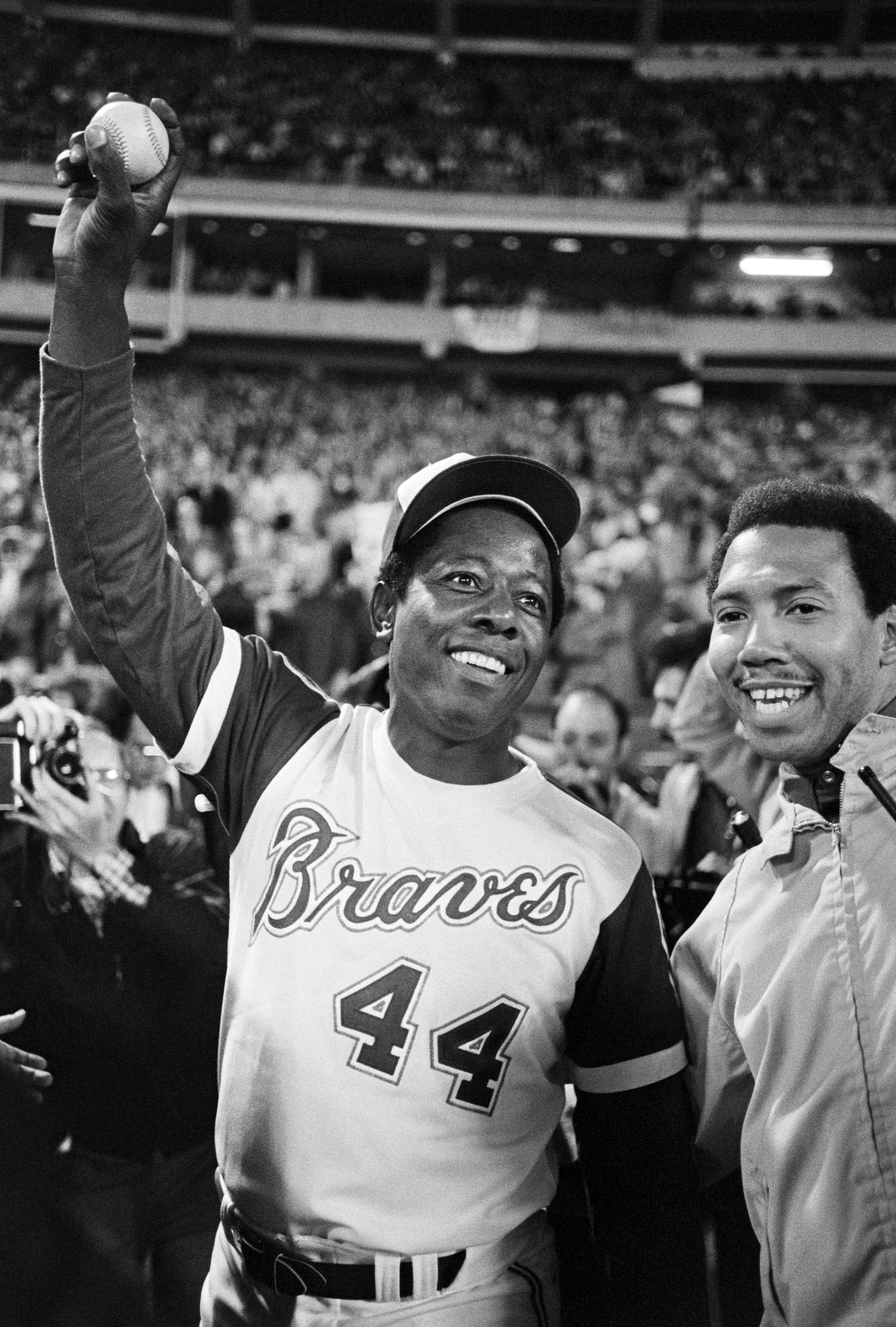

By the end of the 1973 season, when you ended the season with 713 home runs, the biggest crowd Atlanta had seen up to that time — 40,000 people — gave you a five-minute standing ovation. Tell us about that moment, and what it meant to you. Did you think racial attitudes were starting to change? Here you are in Atlanta, you weren’t too sure when you first came that they were going to even accept you and now you’ve got the whole stadium standing up?

Hank Aaron: Isn’t that something? That’s what it is. It just gradually turned out that way. I came here for one reason: I came here to play baseball. I came here to entertain people. That’s what baseball players are about. You know what I mean? They’re entertainers. When you go to a stage to watch someone perform on stage, to sing a song, that’s what baseball players are for. I had given everything that I had. So they felt like, “This man has given us all, and we need to get up and clap for him.” So I felt wonderful. I felt like, “You finally arrived. You finally got what you wanted to get.” And it’s been wonderful ever since.

What do you know about your achievement now that you didn’t know or understand when you first started your career? What does achievement mean to you?

Hank Aaron: It means that you have fulfilled your obligation. When I say obligation, you fulfill whatever thing that you wanted to do. I look at my career…

I was fortunate enough to play 23 years in the big leagues. I was fortunate enough to play 23 All-Star games. I was fortunate enough to have played in 14, 15 World Series games. Games — not series — games. I played in all these, and I won one home run title, batting titles, slugging percentages, and I’ve done a lot of things that I think that I wanted to do in baseball. What it is that some people might have said that you think that you should accomplish that you didn’t? Would you be disappointed? Yes, I am disappointed that I should have done one thing that I should have done in baseball that I didn’t do, and that’s to win the Triple Crown. I came very close twice, and I didn’t do it. One year I think I was off to the greatest start of my career, I don’t know what year it was, and I sprung my ankle in Philadelphia, and I was out for a long time, and I got off to a good start. But I thought that I should have won the Triple Crown at least two years.

You’re one of the greatest stars in the history of the sport. How does that make you feel?

Hank Aaron: I feel great! I gave baseball everything that I had. That’s the way that I did every single night that I played, or every day that I played. When I walked off that field, no matter where it was or when, I could walk in my hotel room and look myself in the mirror and say, “Hey, I gave it everything this afternoon that I had.” Sometimes I would go 0 for 4, sometimes I would go 4 for 4. Sometimes I would have two home runs, sometimes I wouldn’t have any. But I felt like, it just makes me feel great because of the fact that I didn’t abuse what I had, what God gave me. A lot of players, a lot of players I’ve seen, and I played with a lot of players that abused their ability to play the game. They took for granted that, “Oh, I got this ability to play and I can play it, no matter what.” I can almost tell you, if I hit — I never hit no more than 44 home runs — but I could tell you, the day after the season is over with, if we sat down in a corner and you said, “Who did you hit these 44 home runs off of?” I could almost tell verbatim who I hit those home runs off of. Yes.

That’s how much it meant to you.

Hank Aaron: Yes. It meant that much to me. I studied the game. I knew exactly what I wanted to do and I was very proud of my career. I was very proud of the fact that I was able to play baseball. I took advantage of all the ability that I had. I could run the bases. Fortunately for me, I played in a small town, which was good for me. A lot of people say, “What if you had played in New York?” Everybody can’t play in New York. “What if you played in Chicago?” Everybody can’t play in Chicago. Somebody’s got to play in small towns. I happened to play in Milwaukee.

You’ve named your education foundation the Chasing the Dream Foundation, to provide opportunities for disadvantaged kids. Why is this so important to you? I presume the dream you’re talking about is the American Dream?

Hank Aaron: That’s true, but I think it goes a little bit deeper than that. As a little boy, growing up in Mobile, Alabama, I dreamed of playing baseball. I wanted to play baseball so bad, and had nobody to help me, so I just thought that if I ever get in a position to help other children, regardless of whatever color they may be, and chase their dream, I was going to try to do everything that I possibly could. Of course, when I retired, the Commissioner — who is now the Commissioner, Bud Selig, who owned the Milwaukee Braves at the time — was my boss. And the year that I retired, he said, “What would you like to have? Would you like to have a trip around the world, or would you like to have a trip?” Would you like to have a lot of things, I said, “Commissioner…” it wasn’t the Commissioner — I said, “Bud…” — he and I were very good friends — I said, “Bud, what I’d like to have is some kind of foundation, that when I retire from baseball that it would last, and go on and on and on.” And that’s why we call it Chasing the Dream Foundation.

What does the American Dream mean to you? Do you feel it was there for you to reach for when you were a young boy?

Hank Aaron: No, it wasn’t. Let me put it this way. It wasn’t there when I first started. Of course, Jackie Robinson coming in, being the first African American playing baseball, he kind of opened doors up and made the playing field a little bit level for everybody. I took advantage of it myself, players like myself, Willie Mays, and some of the other great black ball players. But no, it wasn’t there at the time, and I think things are a lot better now.

We have to thank you athletes for opening the doors for so many other African Americans, and other people of color, because without what you did, that opened the eyes of the American people, maybe we would still be back where we were then. Do you think of it that way?

Hank Aaron: I feel like we made a contribution. When you start talking about the real dream, you start talking about Dr. King, of course, what he did. But I think athletes played a very important role in what America is today, no question about it.

In October 1972, Jackie Robinson died. He gave a talk in Cincinnati a couple of weeks earlier, and then went to the Oakland clubhouse to talk to the players. None of the black players paid any attention to him. Why?

Hank Aaron: I don’t know. I can walk in the clubhouse sometimes and be shunned like that. I don’t know. I wished I knew. I don’t have an answer for that. I think about that quite often, even now. Even since they’ve done 42, the movie, I think about that. There is so much in Jackie’s life that was not told, because they couldn’t tell it all. I don’t understand it, especially from black ball players.

Do you think they just live in the moment? They don’t even think about history? Maybe they didn’t know who he was.

Hank Aaron: I think the game itself meant an awful lot to them. This happened in Oakland, I believe. They just thought about the game. They weren’t thinking about Jackie Robinson, they weren’t thinking about his contribution or the role he had played, and the reason that they are in the big leagues. They didn’t think about it. They just thought that one day they jumped up and they were in the minor leagues, and the next day they jumped up and they were in the major leagues. They didn’t think there was somebody else, a foot soldier that paved the way for them to get where they should be.

There are so many athletes who had no savings or assets at the end of their athletic careers. At one point, prior to breaking the home run record, you were struggling financially because of bad advice and poor real estate investments. Yet here you are now, a very successful businessman. To what do you credit that?

Hank Aaron: Most African Americans and especially ball players come up, they don’t have the knowledge of saving, what to do, and they don’t have people to come to them and tell them how best to make an investment. I was no different than anyone else. We was busy trying to be part of what we called the American Dream. We didn’t have time, and when I say, “Didn’t have time,” nobody never came to us and told us that, “We would like for you to invest here,” or, “Do this, and do this,” and “Save your money.” So actually we were all guilty, myself along with the other black ball players. But the one thing that I think that helped me more than anything, I think that after playing for so long in Major League Baseball, I went through a period… I started when I was very young. Let me start back. I was fortunate enough to start playing when I was 18 years old. After graduating from high school, I started playing. I only spent a year-and-a-half in the minor leagues, and I got to the major leagues. So I was able to go through some periods of losing — well it didn’t make any money. I take that back, I didn’t have anything to get rid of, because I didn’t make any. I think it took me 10 years, after having great years, to even get to making 75,000 dollars. So I didn’t really make any money. Really, I started making money probably when I started chasing Babe Ruth’s record. I started signing on to do advertisements and things like that. But I wasn’t blessed like a lot of ball players in New York City to make a lot of money.

It sounds like you weren’t in it for the money. You were in it because you liked what you were doing.

Hank Aaron: Believe it or not, you can put it that way. I didn’t know anything. I loved baseball. I loved the challenge, I loved the competition. I loved to outguess the pitcher. It was a great challenge. It was great for me.

Did you wish after the big hit, when you broke the record, did you ever wish that Jackie Robinson had been there to see you do that to break Babe Ruth’s record? And what would you have said to him afterwards?

Hank Aaron: I think he was there in spirit, really. I got to talk to Jackie many, many times before he passed away. In fact, when I signed my first contract with the Braves, I remember playing an exhibition game against the Dodgers, in a little city. In Memphis, Jackie, Camp, and Don Newcombe were all sitting in the hotel, in a room, and they were all playing cards. I was in the corner watching them. Just standing there, watching with my mouth wide open, trying to make myself realize, “Oh God, am I here?” And to watch these guys play? But to answer your question directly, I think after that, I remember him telling me that the one thing that you have to remember about baseball is that the only way that you’re going to do something good for your team is that when you stand at home plate, make sure that you touch all the bases and get back to home plate, and that’s when you’re making a contribution to your team. He always said that. He always just said to just be humble at what you’re doing, and try to give all you can, and everything that you can to the game. And that’s what I’ve tried to do.

You end your autobiography with a quote from Jackie Robinson: “Life owes me nothing. Baseball owes me nothing. I cannot rejoice while the humblest of my brothers is down.” What did that mean to you?

Hank Aaron: I felt like things had been good for me, but when I think about all of the other black players or other black people that are still down in the hole, hollering for help, that until they come out, all of them come out of their hole, and be able to have the playing field level, then none of us should be able to rejoice, because things is not that good.

Well said.

Hank Aaron: Thank you.

And thank you for speaking with us today.