Do you have a faith or a set of beliefs that kept you going through all of that?

Beverly Joubert: I am spiritual. I’ve always been spiritual. I don’t practice a religion at all. I feel like there’s a lot of dogma around that and a lot of control. So no, I don’t. But I do believe that we are energetic beings and what is sort of governing us in life is love, and we’re all connected. Truly, you and I are connected in that way. So I believe in a presence — a presence. I’ll tell you what I said on that night, which was something I’ve never said in my life before, but I actually quite silently said, “Light, divine hope.” So I do believe that there’s a presence. I believe that we are living on this planet in a way to be more effective. I think we are all meant to be doing the work of protecting our planet, showing love for each other — protecting and all the conservation work that we have to do. So my beliefs might sound a little different to everybody else’s, but I do believe that I was in a sort of a wonderful protection at that time.

Dereck Joubert: I think that many religions have overcomplicated themselves. And I think that what we believe in is a far simpler version of that.

Now you look like nothing happened, but you’ve been through a lot. What was the recovery like?

Beverly Joubert: It’s a year and three months since it happened, and I was in hospital for three months. I came out with still a lot that I had to do myself. So I had to sort of be in rehab for eight months, and a lot of that rehab was just simply being able to open my mouth. When I left hospital, I couldn’t even open my mouth. I could get one finger in and that was it. So I had to, on a daily basis, jack my mouth out with those splint sticks and put them in, one on top of the other, until — it wasn’t very attractive, I can tell you — but until I had about 19 in my mouth, and you just see tears rolling down my cheeks. And that was to be able to get my mouth open, for many reasons — just to eat. Dereck had been told, when I was in hospital, that I would never eat again because my epiglottis had folded backwards, and then, of course, I had all these holes in my throat. So for two and a half months, they fed me through the jugular, so nothing went into the stomach at all.

But you know, it was all part of the healing phase. I kind of put myself into neutral. I said, “This is what’s going to be, but I’m also going to use this time.” When I was lying in hospital, I thought, “Why am I here? What is it? What do we need to stop and reflect on?” And there were many things. I mean we had got to the point, probably two months before, that we were feeling really desperate about where we are on this planet. So we needed to clearly get ourselves out of that depression because you can’t be effective if you are in that phase.

The other thing is that I started looking at the women that were looking after me. Obviously, I had seven surgeons, and they were phenomenal. But the nursing sisters, each and every one came from a different place in Africa. So it gave me an opportunity to chat with them, to find out who they were, what their lives were like, and it was a little bit of an investigation on what’s happening to women. And it was sad. They’re very proud of who they are and very passionate about their job, but they all had hard lives, and a lot of the hardship was that they weren’t respected in Africa — you know, a patriarchal society through many parts of Africa.

Do you think you’ll do some things differently because this happened to you?

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely, absolutely. I came away going, “How can we be more effective in helping women as well?” So in a lot of our work, we are — we’ve got a foundation — and we are looking at how we can bring them into what we’re doing, especially with the young girls. We can start helping and educating young girls on how to protect themselves.

You’ve had a very, very close call. What do you do next?

Dereck Joubert: I think that we’ve had a great opportunity from this to recalibrate and to think about what is next and what this has meant, what the meaning of this is. I think that there are a number of styles of people: some that would be terribly traumatized by this and retreat; others that would be far more cautious, definitely; but for us, it’s completely different. This is an opportunity and something for us to lean forward into — in fact, use as a great platform, as a great lesson, as a great opportunity to recalibrate, so we’re doing that.

Part of it is that I think that it’s okay to redefine yourself from time to time. I think that as humans, we start off on a certain path in life as young people, and then we hang onto that, and we define our success or failure about how close we get to those goals. I think we’re reluctant in many ways to have faced two and three and four and five, and they all look completely different. I think that we can be different through our lives.

What’s the lesson you learned from that near-death experience?

Dereck Joubert: I think the big lesson for us is that all you have to do is spend a moment holding the hand of the person you love as she’s dying, or has died, and wishing, praying, for another minute, another second, another month, another year, to realize that if you get it — and in this case we did — you’re not going to waste another moment with anything that’s irrelevant. So for us, what that means is if it’s not saving the planet, or doing the sort of stuff that we really need to do, or having fun, then it’s not worth getting out of bed for. So that’s really where we’ve — we’re like laser-sharp focused now.

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely.

Are you going to go back?

Dereck Joubert: Oh, we’ve been in the bush.

Beverly Joubert: We have been back. We started filming again in August. We also relocated a lot of rhinos. We haven’t spoken about our Rhinos Without Borders program. A couple of years ago, we said that we would move a hundred rhinos from the highest poaching zone in one country into the lowest poaching zone in another, and we started that journey. We’ve now moved 77, and we’ve got 16 babies that are born in the wild, which is really exciting.

But my first project back was, first of all, going back to the area that the accident happened — coming to terms with it. I wanted to make sure I had no demons. And then sitting with a buffalo herd and photographing their horns — obviously, the horn was the key part that went into my body — and all was fine. But we spent a fair amount of time doing that. And then we moved 16 rhinos in that August, as well.

It was a phenomenal soul food for me. I really felt that I was back. I might not have been as strong as I wanted to be, but it really was quite a challenge because a lot of the moving was through the night, and I think we dropped into bed at four in the morning. And as I went into bed, I thought, “Wow! Against all odds of me surviving, and really being deconstructed in less than three seconds, and here I am.” And sometimes, we pinch each other, and we say, “My gosh, isn’t it outstanding that this is where we are? We did survive.”

So right now, I probably see it a little bit as a dream, but I have embraced it in every way. I don’t want to be a victim to it. I often think that we don’t choose life lessons, and this was a lesson that obviously was quite a tough one, and it came our way, but it was an important one. It gives us the true values of life. It gives you complete perspective. And I find that I, now, unlike my solitary years — just Dereck and I and not needing anybody — I still don’t need anybody, but I’m immensely appreciative of every human being that we have touched and has touched our hearts and cared for us through that phase, just sending us messages. Those messages were so phenomenal that I felt like they were holding us up, and we had a purpose.

The life the two of you have lived in the wild sounds so magical, but sometimes it also sounds a little crazy.

Dereck Joubert: It was totally crazy. I think it’s good to be a little crazy, isn’t it?

Beverly Joubert: I have to say, though — many will say, “Oh, so romantic living out the way you do, just the two of you out in the field!” And that’s really — it was our desire to be able to be together and work together and share the passions together. So yes, very magical in that way, but incredibly hard. You’re living hours that are just exhausting. We would often be — through that time we would work from four in the afternoon until nine in the morning. And granted, we might have gotten an hour of sleep through the night, but an hour sleep is not great for the logging of memory in the brain. And then we would try and sleep during the day. Then our lives changed, and now we work for 18 hours a day and manage to sleep through the night, but you are being physical at all times.

Let’s talk about the physical part of this. How did you keep your food and everything in the truck?

Dereck Joubert: We’ve designed many vehicles. One design leads to the next, to the next, over the years. So you get a vehicle that looks great, and then when you’re working in it for many, many hours through the night, you realize that you keep bumping your head on one spot. So the next vehicle you design, you cut that out, and actually, our vehicles have gotten more and more simple over the years. But within the vehicle itself, we treat it like a ship or like a boat or a yacht. So everything has its place: camera has a cutout where the camera goes; lenses, knives, axes, food — everything is in that vehicle so that we can reach over in the dead of night and pick up something. We know the axe is there, or the lens is there, or where the food is, so that if it’s chaotic, then your life is — it’s actually quite dangerous.

Is there anything that you kept in the truck that we might not expect?

Dereck Joubert: The complete works of Shakespeare.

Seriously?

Dereck Joubert: Very often, with just a candle, I’d read Shakespeare to Beverly — and start at the beginning and end up at the end of the complete works and then start again. I think it’s an enduring piece of literature.

Beverly Joubert: It was really good for crafting storyline as well. So I think you really enjoyed it for writing, didn’t you?

Dereck Joubert: Yeah.

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely. What else you wouldn’t expect? Well, we would have a solo shower. Keeping ourselves cool and clean was really key to us. Even though we were in the bush, we didn’t just say, “Oh well, that’s it, never going to brush my hair again.”

It’s important to feel that you’re still a human being, having a lot of pride for yourself. I think, especially being out in the field, it’s really important to be clean because there are so many bugs and little things that can start living off your body!

Dereck Joubert: And also, this is where we live. This is our home and our office out there in the bush. For many people, it’s a place you visit for two or three days or a week or two. You can suspend your daily routines if you’re going in and out. If we lived like that, we would have hated it, we would not have been able to spend the amount of time that we did out there. So we made sure that we were clean, we were healthy, doing exercise every day, and working with lions and hyenas.

What kind of exercise did you do?

Beverly Joubert: I’ve always done yoga. So I would get on the top of the vehicle, and I could do my sun salutations on the top of the vehicle. I remember a key moment when we were following a little leopard, and she was reclined in the tree, and she was there for hours and hours and hours. And often you could be there through the whole day, and that is the time that — sitting patiently — we would do a few things, but obviously never wanting to disturb the animals around us. So I got out of the vehicle and I just did everything where she couldn’t see me. And that’s the sort of thing we would do.

Dereck Joubert: We would do sit-ups. This little leopard would eventually come underneath the vehicle if it was a hot day and just sleep there for hours and hours and hours. So our lives were filming, Shakespeare, hundreds and hundreds of sit-ups, filming, Shakespeare, hundreds of sit-ups.

Hundreds at a time?

Dereck Joubert: Yeah, you just do hundreds. You do whatever you can within a confined space. A little bit like living on a submarine, I imagine.

You said you had a shower. How did you take a shower out there in the bush?

Beverly Joubert: It’s just a tiny little — it’s made out of plastic, and it’s black to attract the sun, and we would put it out on the windshield because our windshield was folded down. So it would be on the hood of the vehicle, and that would attract the sun, and then we would just hoist it up into the tree and have a shower in nature, and it was absolutely divine.

Do you think you could have spent all of those decades out there if it was just one of you?

Beverly Joubert: It would have been a different situation. I think we would have constantly been going into town, especially if we were still together. We would have been going in to see each other, whereas this allowed us to just be in the field. I think what is so important about just being in the field — which many researchers don’t have the capacity to do — is you miss way too much. We’re not in control of when it all happens, and it often happens when you’re not there.

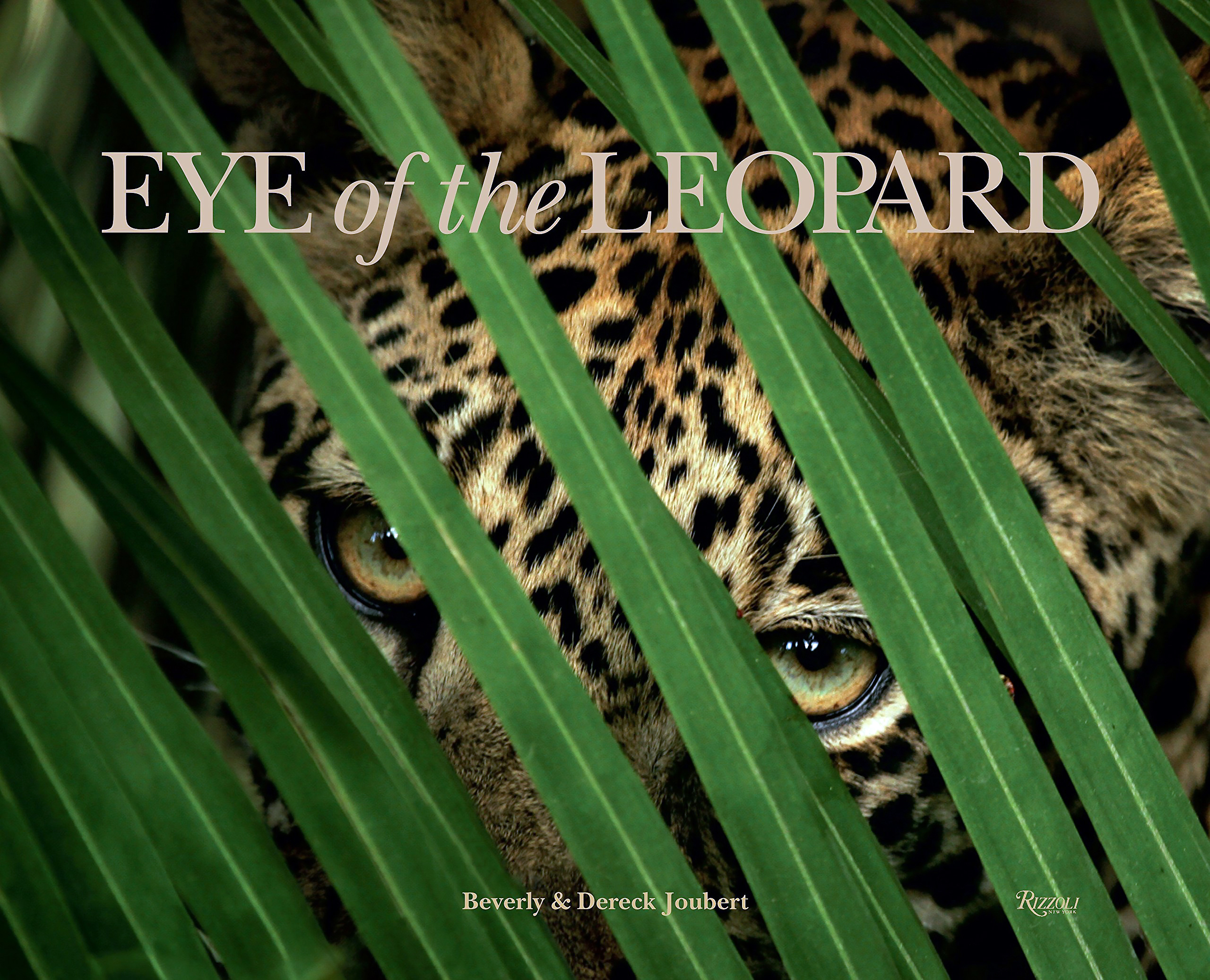

You spent four and a half years tracking one leopard. Is that right?

Beverly Joubert: That is right. We found her when she was tiny.

How did you do that? Did you follow the leopard in the car?

Dereck Joubert: We found her when she was eight days old and she was with her mother. So we just decided to move in with them. So every day we would find them, or if we had lost them, we would track them and find them. And then just spend as much time with them as possible. So every single day, we would be up at 3:30, four in the morning, go out, pick up the tracks, find her, find her mother, possibly, and then stay with her the whole day, until nine, ten at night.

How do you know they’re her tracks? Couldn’t it be another cat’s tracks?

Dereck Joubert: Yeah. So every leopard has a different track. Like yours, I’d be able to pick your tracks up if I understood your feet. Leopards — I had an engineering vernier, so if I picked up the track, I’d measure it and say, “This is Legadema,” or “This is not her because she’s gained three centimeters.” So there’s a science to it.

Beverly Joubert: But we eventually had this incredible relationship with her. If you spend that amount of time with the cat — and we found her, as Dereck said, at eight days old — so slowly, we spend more time with her than her mother. Her mother would go hunting, maybe two days at a time, and we would be that constant. We were always there. So it came a time that she started looking at us, wondering who we were. And then, as we all know, cats are so curious, she eventually came to investigate us. And once she realized that we were a safe zone for her, we were pretty much a part of the forest, but we were more than that. And we eventually — I think when she got to be about six months old, we realized that we had broken a sort of spell, that we were more, and possibly like surrogate parents because that’s the way she treated us. Often, there were times where she was in danger, and instead of going back to her den, she would come and go underneath our car.

What did that feel like for you?

Beverly Joubert: It was an incredible privilege. I mean how can you not enjoy that? But we knew that there was a fine line, and we didn’t want her to get so complacent around humans that one day it could hurt her.

Dereck Joubert: It’s at first gratifying to have that trust because I think that one of the things we’ve lost — over the 60,000 years that we’ve been in this sort of shape and form as humans — is we’ve lost that trust with wild animals. We’ve persecuted them for a long, long time. So to have an innocent leopard suddenly break through that and realize that she could trust us — and us, specifically — that’s very gratifying. But it comes with a huge burden because then she could walk to another vehicle, jump into that, and they wouldn’t react the same way. So we had to be very careful about that.

Is it true you used to go walking with a herd of zebras at night when the lions could be stalking them?

Dereck Joubert: We were trying to understand what it’s like to feel like a zebra in the middle of the night, walking through the long grass, knowing that lions could attack you at any time. So we got in behind — you were driving — and then I got in behind a herd of zebras and just walked with them, and it’s very, very eerie knowing that you’re prey in an environment like that where there are a lot of lions. So I think it’s about breaking down those barriers.

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely. And there would be times — obviously exercise is key as well — but this particular time Dereck’s talking about, we would — through the night, we were on the move following lions. So what he eventually worked out is you can put the vehicle into the second gear, lower range, and we would both get out of the vehicle. We’d be right next to the vehicle because obviously, we don’t want to disturb the situation that could happen or the animals around. So we would just walk next to the vehicle, just to be able to get that sensation, but also to get exercise at the same time, and it was key. I think it was key to bringing in that tension. When you produce a film, you need to know what everything is feeling.

So that’s why it was worth the risk?

Dereck Joubert: I think there’s a real danger that as we’re talking about Africa, that we present a “Disneyfied” version of it. What we’ve always wanted to do is present a real version of it so that we understand the protagonists and what it’s like to be a hyena racing into a lion kill, or a lion being attacked or mobbed, or a zebra walking in the night. So we need to feel that. Only once we felt that and understood it could we write about it in the film with any sense of empathy, I think.

When you were walking in the moonlight with the zebras, what did that feel like?

Dereck Joubert: Wow. It was actually profound. You feel very vulnerable — very, very vulnerable — in that every crack of a grass stalk nearby, you think there’s a lion attached to that, where it might be a mouse. So every hair on your body is standing upright, every sense of survival is crying out to you that you better be alert, and your twitch muscles are already halfway twitched, so you can imagine what it’s like to be a zebra. Our defense mechanisms don’t allow us to do this all the time. That’s why it’s so extreme. But zebras and other prey animals are not like that all the time. They’re in a fairly relaxed state going into it, and then they have these action moments, and then they forget very quickly. It’s their only mechanism; otherwise, they wouldn’t cope. In the same way as combat soldiers can’t stay on high alert all the time because you just wouldn’t cope.

What’s the difference between the Disney version of Africa and the real version?

Dereck Joubert: I would say that the glorified romantic version of Africa and African wildlife that’s often — and even more increasingly — presented to us is that nothing bad happens. Baby cubs grow up, lion cubs grow up, and they become bigger lions, and they become big majestic male lions sitting on Pride Rock somewhere. The bad stuff is very often hidden. For instance, you don’t often see that — as we showed in one of our films — that a beautiful lion cub of three months old can have its back broken by a buffalo and survive like that for a week, struggling, and pulling its back legs along. Do we need to know that or not? Not really. I think, in our films, we try and point to it. We don’t linger on it, but I think giving a more balanced view of what happens in the harshness of nature is the very reason that we do our films — and that we should all be doing films like this and tell these stories — is because the things that go on in nature are parables for the things that go on in our lives. We need to learn from nature to have balanced and rounded lives ourselves. So when we’re children, we think nothing can go wrong but need to prepare ourselves for the time when our parents die or our grandparents die. One of the reasons we have pets, I think, is so that we can preempt the moment of discovery of death within our lives.

Because your pets die on you?

Dereck Joubert: Sure.

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely. You have to understand the life and death struggle that is happening globally, and it’s happening not only to the furry creatures out there, but it’s happening to the humans. I think it’s important for us to see similarities. We are just another animal species, and I believe if you understand the wilderness, and you try and emulate what is happening in nature, I think we would have a more peaceful world. I think we would get on with each other and probably wouldn’t have such extreme xenophobia. We would accept cultures; we would accept each other.

Dereck Joubert: I think of the lessons, as well, beyond simply death. So there are many lessons from the animal world that we can draw on, that I think we lose the opportunity of if we just paint the glorified version. So I think that, for instance, we should be learning from elephants about empathy and trust and respect and intelligence and caring, and even the ritualization of death, and draw that into our lives. In fact, if we look at what elephants represent and what humans represent, they’re very, very similar. We have language: we have concepts of past, present, future, all of these things. The one thing that we don’t have — or that we do have, sorry — that elephants don’t is the capacity for cruelty.

Out there in the bush for months on end, just the two of you, do you ever get sick of each other?

Dereck Joubert: Well, I was a bit worried when I was walking with the zebras and the car stopped!

But when he’s read Hamlet to you over and over again, and it’s hot and sticky, don’t you ever think, “Maybe I don’t need to do this anymore”?

Beverly Joubert: It’s very hard to get me out of the field, especially if we’re about to go on a trip. This is my soul food, being out in the wilderness area. I think we have such a balanced life. We probably have a more balanced life than most people in a relationship. I think the danger in a relationship — when you’re living in a society, you’ll often find there will be individuals that think they’ve been caring, but they’ll poke holes into your relationship, and you start thinking, “Yeah. Damn right, he shouldn’t have said that.” Whereas, Dereck and I have to sort everything out ourselves. So communication is key with us in the field, wherever we are, and I think often our communication — because we’ve gotten to know each other so well —is that we can sit very silently and not say a word to each other. And all of a sudden, one will say, “Yeah, I agree.” And we’ll look at each other and go, “Oh, I didn’t even verbalize it, but yeah, you’re right.” And then we’ll talk about it.

So if you’re giving the silent treatment, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re mad at him?

Beverly Joubert: Exactly.

Dereck Joubert: Doesn’t mean anything to me.

Beverly Joubert: And of course, there’s another reason why you really do have to be in a good relationship. You can’t just storm out and say, “Well that’s it! I’m going to go for a walk,” and not be with each other. Because I think that the partnership that we have in the field is vital for understanding the research, the discovery, but also if something goes wrong, so it’s key to have a partnership.

Dereck Joubert: We didn’t get together and get married so that we could live separate lives. When we started out, we said, “We’re in love, hence we want to spend our lives as close together as possible for as long as possible.” So we looked across at some of our friends who were falling in love around the same time we were, and then they were getting jobs in banks and then spending their most precious engaging hours of the day with other people. So we designed our lives the other way around. In fact, all that we do today is really designed around this one premise that we wanted to spend as much time as possible — quality time as possible — every single day.

Your story is an amazing love affair, but it’s also remarkable that you have had a love affair with wildlife. What are the odds that the two of you would find each other, both be interested in the same thing, and still be doing it 40 years later?

Dereck Joubert: I think the two intertwine. I think that we fell in love, and we both had an interest in wildlife, but we went down and developed that and nurtured that interest in wildlife together. It’s not as if we had really 100 percent commitment to the bush and to the wild in parallel. I think we developed that together. It’s funny enough — Robert Redford said this once he saw one of our films recently — and he said, “This is an intimate love affair,” the story between nature and the two us, and in between the two of us. So it was interesting.

You spend months in the bush, waiting for the perfect shot, and then you’re hanging out with Robert Redford. What’s that’s like?

Dereck Joubert: Bob is a good friend, and we really like him. The interesting thing about him is that we share a deep appreciation of the natural world. We find that all of our friends are like that. We sort of gather around this single ideology, which is an appreciation of the natural world.

Beverly Joubert: And then, of course, this last week we were here with the National Geographic doing the Explorer Symposium, and that is a wonderful time for us to reconnect with people that are likeminded around the world — all explorers — and to be able to brainstorm on the way forward. How can we all be more effective in doing our work and convincing governments that new policies should come into play, to protect either a species or a rainforest or a particular area?

I think that that is key, but we only see each other once a year, and every time we see each other, it’s like old friends. We just pick it up and move forward. It’s our soul food because there are times where the emotional hardship — you spoke about the physical hardship — but the emotional hardship really gets to us. We can go into deep, dark depression.

There are times where we look at what’s happening on the planet, and we look at what we’re doing, and you think — with all of this exertion that we’re putting into it — and yet we are still in the decline. We’re still losing species. We still have governments that are unraveling everything and looking at the environment and saying, “Well, that’s not important. What is important is industry.” But you know, we can’t have one without the other. We have to protect our planet. We have to protect the lungs of the earth, and that’s both ocean and forest. And when it seems like you’re losing all the time in your work, and you’re still having safari hunting coming out and killing lions, you take it on personally, and it can be a little bit like a post-traumatic syndrome. I think that what got us both into it is being inspired and the love for nature. What drives us forward is those bleak moments. They’re the ones that push us to say, “No, we’ve got to change this. We have to be able to stop those atrocities.”

In those dark moments, do you ever despair of finding a solution? Do you ever just want to go home and take a real shower?

Dereck Joubert: The solutions are in working through it and visualizing two futures and then opting for the better one. So we go through that exercise quite a lot. You’ll say, “We’ve just come across five elephant carcasses with their tusks chopped out. This is devastating and illogical,” and it makes us angry. So then we’ll settle down and say, “All right, we got to fight this.” So if we retire, and have a shower and a couple bars of chocolate, and get out of it because it’s too emotionally hard for us, this will continue. So the solution to that problem is us. And then we lean forward into it and paint a different future.

We understand the moments when it’s hot and you have to be patient, but there must be funny moments that also happen out there. Can you remember one or two?

Beverly Joubert: Oh, gosh. There are so many. In fact, some of our disasters have turned into funny moments. Now and then you talk about the heat. We found a very sandy patch where you can see there are no crocodiles coming into the area, and you sort of drop into the water and just soak up this beautiful Okavango water and enjoy it. And the next minute you come out, and you see that you’re covered in leeches. Of course, we always found it really funny when it’s on somebody else, but not on yourself!

Dereck Joubert: One of those open areas, once we were driving along at sunset, and a beautiful hard-baked pan — open area —so I stopped the vehicle. And I took Beverly’s hand, and we went out there at sunset, lions calling in the distance, and we danced the tango on this pan and then walked back to the vehicle after the sun was down. And I said to Beverly, “So if some bushman walked through now and was reading these tracks, what do you think he would say?” And the real answer is, he would have gone, “Tango!”

Did you have a radio? How did you listen to music out there?

Dereck Joubert: We had music in our head.

Beverly Joubert: Totally music in our heads at that time. But we don’t really listen to the radio, and we don’t listen to music at night. The music that we listen to is really the chorus of what’s happening out there. You hear a lion roar, and a hyena give its call, and then a little jackal, and then all the owls would start, and all the little bell frogs if you were close to water. It really is a cacophony of just the most incredible sound. So that is our music.

Dereck Joubert: We had a lot of fun moments with that leopard that we were following.

Beverly Joubert: Oh, we did.

Dereck Joubert: I remember she and her mother were just going through a split-up. It happens to all leopards at a certain time. She was 13 months old, and her mother had just killed an impala and brought it up a tree. The little one got there and completely messed it up and dropped the impala, and the hyenas took it. So it didn’t bode well for a peaceful afternoon. The mother was growling at the little one, and she didn’t know, she had never had this in her life before, so she came to us once again for support and comfort. She was lying on the side looking up at Beverly, and sort of meowing, and then moved away again, tried to get close to her mother, got rejected. So Beverly started to record all of this, and she had a rifle mic with a furry cover on it, and she put it down, and that was enough distraction for this little leopard. She pounced on this thing as if it was a young animal and ripped it away from Beverly, and the two of them were having this tug of war on this cable. The leopard wanted it as much as Beverly.

Beverly Joubert: So I was holding onto the cable because otherwise the Nagra (microphone) and everything would have gone, but eventually I managed to reel her in.

Dereck Joubert: So it’s those moments that are lighthearted every day.

Beverly Joubert: We had a time where we really realized that she was completely comfortable with us. She might have been about 13 months old, also reclined on a tree, and Dereck and I would be sitting in the front seat. He was writing a journal at the time. I was cleaning my gear, and we could see that she really recognized us as individuals. I climbed to the back to just make ourselves some tea, and in her eyes there was excitement. She jumped down — it was the first time she ever did this — and she just leapt onto my seat, and she sort of looked around very proudly as if to say, “Oh well, this is interesting, and I’ve at last made this bridge.” But instantly, we both knew how dangerous this was for her.

Most people, by the way, would think it’s dangerous for them! There’s a big cat right next to you in the truck.

Dereck Joubert: I know.

Beverly Joubert: So we sort of looked at each other, and I said, “Well, I could sort of do a snarl like her mother, but my teeth don’t really look as effective.” Dereck did the finger (wagging) for a moment, and she did not appreciate the finger. So what Dereck did is he put on the ignition, and then he put on the heater in the vehicle. Now even though we’ve got no doors and all that, there’s still that fan that works, and our fan had a little — I think it was just a little leaf trapped in it, so it made a rattling sound a little bit like her mother if she was growling at her. And of course, the hot air was blowing on her, and she really didn’t like that, and she got the message. She jumped down. She tried to try it one more time, and we did the same, and she never did it again. And that was the only way to protect her for the future, you know, if she ever tried to jump into anybody’s vehicle, and so that never happened.

On these trips, how long would you go without seeing another human being?

Beverly Joubert: Gosh, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, it would be forever.

Dereck Joubert: This actually is interesting because we were living way out in the Linyanti area, northern part of Botswana. And we had arranged — because it was before I had an aeroplane — so we had arranged for people to drop food at the nearest airfield for us, every two weeks. We would drive out, collect our food, and then continue. So we had gone about 270 days then without seeing anybody, and we got to the airfield, and our watches had been damaged and broken, so we were a little bit out of sync. We got to the airfield, there was no food there, and then we heard the plane coming with our food. But we knew we had a problem because, as the plane was landing, we backed off into the forest and watched them unload food so that we didn’t have to interact with anybody. And then we went down and got our food once they had taken off. We then realized that perhaps we needed to get out of there.

And did you?

Dereck Joubert: A few months later, yeah.

Beverly Joubert: But of course, it’s all changed now. I suppose now we’ve modernized. There’s Internet. We’re more connected.

Dereck Joubert: We’ve got a plane, so I can fly in and get to our own home. So we interact more with people now, but that was the pinnacle of our reclusiveness.

Has the success of your movies and books helped you have more money so that you can have more comforts — a plane and different things?

Dereck Joubert: What it’s done is, it’s given us a revenue stream, which is fantastic. We were just saying the other day, “Boy! We’ve never wished for more money, but every now and again, I wish I was a billionaire because we could give so much away.” So many of our conservation projects are underfunded, and I’d love to be able to write a big check to save lions forever or to save elephants forever; to move a thousand rhinos, that sort of thing. I think that we’re getting there. We’re able to give more money away because it’s just two of us. We don’t really need a legacy of leaving an inheritance to kids or anything else. Our legacy is what we leave for the planet.

Have you ever had trouble with animals stealing your equipment or anything like that?

Dereck Joubert: Yes, often.

Beverly Joubert: Many times, especially when we were doing all that nocturnal work. As Dereck explained, everything would be lined up; sometimes it would be in sort of little foam compartments. And I remember once listening to hyenas crunching, sort of in the distance, and looking down and going, “Oh my gosh, what are they eating?” They were eating the light meter at the time. They stole my shoes many times. I couldn’t leave them on the floor of the vehicle. I’d always have to put them high after that.

I remember it’s freezing cold in the winter months, and I just hung my sheepskin jacket at the back where we were sleeping. And the next minute, we watched it sort of swing and then pull — and “grr!” — and looked up, and there was a hyena with this one. I was not going to live without my sheepskin jacket, and I just leapt out of the car and ran, only sort of halfway thinking, “Gosh, what am I doing?” But he dropped it, and I got my sheepskin jacket back.

Dereck Joubert: Once we were living in a semi-desert area, in a tent — decent tent — and we left about a half a cup of water inside the tent. An elephant came in, smashed the tent for that half a cup of water —rolled it up, completely destroyed it.

Beverly Joubert: He didn’t even get to the water.

Dereck Joubert: No. So then we decided that tents were probably a bad idea. So we built a little grass hut, and it didn’t have a door on it, but we had a freezer in there to keep the film stock in. We went out one night, and we were filming away, and when we got in, we found hyena hairs on the bed that he had used as a step to get into the freezer and stole all the film. Fourteen rolls of films were taken.

How much work was that?

Beverly Joubert: That was months and months and months.

And you couldn’t get it back?

Beverly Joubert: Well, no. So the story goes on. We were desperate because it was the first time to unveil that hyenas actually make their own kills. So they’re not only scavenging from lions. We had filmed this hyena going into a zebra herd once again, and they took down a baby foal. It was devastating to watch, but we had captured it on film, and one of these rolls was that take.

So Dereck is a great tracker. He started tracking this hyena all the way into the forest and then saw drag marks, and then one can of film, and then drag marks on another, and he eventually got them all back into the box. But the one can, which happened to be this particular can, had a bite mark right through it, and so when it was developed in London, they said, “What do you guys do with your cans?” Fortunately, the black bag had protected the film. But yes, every now and again…

So you got it back?

Dereck Joubert: Everything.

Beverly Joubert: But every now and again we do lose.

You said it so casually: “The hyenas do their own kills.” And they’re right in your face. Aren’t you ever worried about that?

Beverly Joubert: We’re not their prey. So there is that. And obviously, there are times where there might be a wounded animal and it will all go wrong. With the hyena clan, that’s when you want to worry. When it’s an individual, and they come into the camp, they’re just coming to investigate and scavenge. You don’t want to do anything stupid. It is better not to be around them at nighttime. All the nocturnal animals come alive, and they’re more confident at night than they are during the day.

Dereck Joubert: I had an incident once. Beverly had some flu, so we went back to camp. We both got into bed, and about two in the morning, I heard hyenas going crazy. So I got out, left her in camp, went down to the nearest water hole, and there were 40 hyenas trying to kill a buffalo. I thought it was worthwhile filming. I parked the vehicle there, and it was when we had the car batteries connected to lights, so I filmed away, filmed away, and as I was filming, the 40 hyenas were displaced by another 40 hyenas from a separate clan. So I was in this basin with 80 hyenas around, and they had half-killed this buffalo, so they were full of blood, and it was very eerie. It was like having gone to hell.

The next thing, they lost interest in the buffalo and came to me. I didn’t have doors on the vehicle, and they started climbing into the vehicle. So I started the vehicle, but in fact, the battery was flat then because of the filming. So all I could do was eventually jump out, run around the vehicle, chase all 80 hyenas away — and you kind of get one shot at this before they find out you’re faking it. And then I ran to the back of the vehicle and started pushing this vehicle, got it onto the roll, rolled down, and it started in gear, and I was able to go back to camp. Got into bed, and I know Beverly said, “What’s going on out there?” And I said, “Ah, nothing.”

In one of your books, you wrote that creativity comes from “a passion for wildness.” What did you mean by that?

Dereck Joubert: Fundamentally, I believe that we all have a wildness in us. We have that spirit of freedom, that wildness, and it feeds our creativity. And our creativity heals us. So in many ways, that wild spirit that we have within us is healing. And I think that Beverly’s story is because she had a wild spirit and a spirit that didn’t want to be put down then. And I think from that all things are born: creativity, healing, happiness, love, cause.

Is there an environment that you put yourself in or something that you do to make yourself more creative?

Dereck Joubert: We both meditate, and I think that coming out of that is creativity. Most certainly, I think, from my side, going out into the field, into the bush, is a place that philosophers and poets have gone to for hundreds of years, to get away from the clutter of the city, and to create, and to think, and to be closer to their gods, or God, or their spirit beings, but to find themselves, and you don’t find that in amongst clutter.

Beverly Joubert: I feel, absolutely, being in nature — anywhere in nature — is very healing. I think a wonderful creative space for me is being behind a lens. I shouldn’t say behind the lens, but behind a camera, because what we’re seeing and capturing — and creating that image — I find, is very fulfilling.

Is there some image you’ve never captured or something that you would still like to do or see?

Beverly Joubert: I think what drives us forward is it’s not one image. There are so many scenes; there’s so much that we would like to capture; there is so much that we don’t even know. And I think what is happening, which everybody sort of forgets, is, as we have the climate change, the change in weather, drier areas, animals are forced to interact with each other, so we’re discovering new behavior — out in Botswana, out in Kenya, out in Zimbabwe, right through Africa. And I think that is key. We need to understand why they’re being pushed to interact with each other, animals that wouldn’t normally interact with each other.

Dereck Joubert: I think there is still that image out there — that we hunt every day — that, if blown up on a big billboard somewhere in New York, would deliver the message to everybody in the world, that would be convincing, that everybody would say, “Ah, we get it! We need to take care of the planet.” That one image could do it, and that’s what we’re after every day.

Is there an image that you’ve already captured — among the many, many you’ve taken — that you’re particularly proud of?

Dereck Joubert: There are a lot of images to be proud of. There are a lot of images that I’m very happy with, in the film context, that were very hard to do or that happened in the right moment, and that were the embodiment of the fact that I engulf myself in the spirit of an understanding of those animals at that time.

Can you tell us the story of one?

Dereck Joubert: There is a moment in one of our early films, a film called Eternal Enemies, where we had been working with a lion and some hyenas through the night. At first light, the male lion that we were working with was under siege. The hyenas were coming in and they were harassing him. And from the distance, a male lion, his brother, came running out towards us. We were in a Zen moment. We were able to see this lion two kilometers away, drive around in a big circle away from him, anticipate where he was going to end up.

I changed lenses. I changed the magazine on the camera, changed batteries, just got ready for it, and was able to film a one-and-a-half minute shot of this male lion running in, in high speed, slow motion, and grabbing a hyena. Perfectly framed, it was the perfect moment. But there have been many others like that. I think, from your side, from the photography point of view, there’s probably something within the eyes that you do that I certainly love.

Beverly Joubert: I know there are many images that, yes, I could put up on a billboard somewhere. About a couple of years ago, I decided to go into an exhibition — fine art photography — which I’ve really enjoyed because it’s a way for us to not only speak to the audience that we already have that understand and are conservationists, but it’s speaking to a new audience. So it opens up the discussions all over again.

There are a couple of images right now that I would love to get out because it really speaks about the issues that are happening. And because some of those issues can be really hard, what I’ve done is I’ve done a blend of two images, one that is the spirit of the animal, with these atrocities — not really wanting to mention exactly what it is right now. And I’m eager to get that out because it creates questions. It’s very intriguing and mysterious in its own, but it creates a lot of questions of “Why are we doing this? Why are we harming animals?” “Why are we utilizing animals and their parts?” — either as something to ingest, like with rhino horn, or ivory to create art out of it, yet it should be more valuable on a live animal.

Are you vegetarians?

Beverly Joubert: Not complete vegetarians. We eat in a very moderate way. We’re probably 80 percent vegetarian if you could say that, but we still have a little bit of animal protein.

There are a lot of talented photographers and filmmakers; there are a lot of adventurers and explorers. Why do you think the two of you have been so successful?

Dereck Joubert: I think what it’s been about for us is we haven’t shied away from the difficult. There are obstacles; everybody has got obstacles. To be scared of those obstacles is debilitating. I think that pushes you back into the crowd. It doesn’t distinguish you. We’ve never been shy of leaning forward into the unknown and stepping in there with joy. I think that if you lean back, you have a weak spirit for that task. So find another task where you don’t lean back. Lean forward.

Beverly Joubert: Absolutely. Nothing has been too difficult. In fact, often when we talk about what we’re going to do, we’ll have so many people say, “You’re crazy. You should not be doing that. It’s never going to work,” even to moving these rhinos, and we just launched into it. We started the Big Cats Initiative about ten years ago with National Geographic, and that was all mission-oriented. Once again, people looked and said, “How is that going to be successful? How are you going to be saving cats? You can’t do it all on your own.”

Of course, we couldn’t do it on our own. So it was about raising money and looking for projects on the ground that could then go and do the work. We now have about 73 grantees working in 27 countries and over a hundred projects we’re sponsoring. And each and every one is working with communities, educating them that the animals are worth more alive to them than dead, and that they can live side by side, and showing them how to do better husbandry by protecting their cattle — because obviously, that’s when they mainly wanted to kill them because if a lion killed a cow, then of course, they wanted to kill the lions. I believe that we can find solutions for everything. It’s about rolling up our sleeves and taking action.

You must have needed a bit of money to start off with. How did you get that?

Dereck Joubert: We did need a bit of money, but the only way we did that originally was to go out and earn a little bit of money. So I’d go out and shoot some commercials, take that money and pour that into the film — our first film that we really wanted to make. And again, it sort of comes back to the message to younger people, I think. And that is, there will be a hundred reasons and a hundred people telling you why you can’t do what you want to do.

I think one has to be reasonable and not be crazy about it, but if it’s something that you’ve got in your heart that has to come out, don’t listen to everybody. Don’t listen to all those people that tell you that it’s going to be difficult, or that you can never be a president, or you can’t be a filmmaker and go live in the bush on your own. Follow that, and don’t listen to people who tell you, “You can’t.”

Was there a moment when you thought you’d made it or a turning point in your career?

Dereck Joubert: I don’t think that we have made it yet, actually. I think that becoming explorers with National Geographic or inducted into the Academy of Achievement gives you a license to try harder. I don’t think it’s a license to say, “We’ve made it. Now we can lean back.”

Beverly Joubert: I totally agree with that, but there are little successes. For instance, we fought very hard within ourselves about the safari hunting killing all the cats in Africa. And of course, we’re concerned about everything else, even the elephants. So having those discussions in the right political arena and speaking to the president of Botswana — and in 2004, they stopped all lion hunting after seeing many of our films, and they had the knowledge. In 2011, they stopped all leopard hunting. And then in 2014, they stopped all hunting, and that gave us a little bit of feeling that it hasn’t all been wasted. We have put the projects out there. We have had the discussions, and phenomenal policies have been made in protecting the wildlife, so I think there are small successes. But I agree with Dereck. We can’t stop; we can’t be complacent. Our work has to continue.

You’ve lived your lives in the wild. Do you expect to die there?

Beverly Joubert: That’s a huge possibility because we’ll probably continue into our old age.

Dereck Joubert: Let’s hope we die laughing.

Beverly Joubert: Too true, Dereck.