Very little good could be achieved. Therefore, the system had to be changed.

Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was born in the village of Privolnoye near Stavropol, Russia. From the age of 13, he worked on a collective farm, where his father was a mechanic. He was an exceptional student and earned a law degree at Moscow University, where he joined the Communist Party and became Secretary of the law department’s Young Communist League. After returning to the Stavropol area, he rose in the League hierarchy to become Regional Secretary of the League, and in 1961 first became a delegate to the Party Congress. He spent the 1960s working his way up through the territorial bodies of the Party and continuing his education in agronomy and economics.

As an agricultural administrator and party leader in his native region, he acquired a reputation for innovation and incorruptible honesty, and he soon rose in the Party hierarchy. He was first elected to the Supreme Soviet in 1970, and served on commissions dealing with conservation, youth policy, and foreign affairs. In 1971, he was elected to the Central Committee. In 1978, he became First Secretary of the Stavropol territorial committee, and by 1980 was a full member of the Politburo.

The death of the long-time General Secretary of the Communist Party, Leonid Brezhnev, presented a brief opportunity for change in the Soviet Union. Brezhnev’s successor, Yuri Andropov, appeared to be grooming Gorbachev as his own successor, but after Andropov’s unexpected death, Gorbachev was passed over for the top spot and the aged Konstantin Chernenko came to power. When Chernenko too died barely a year after taking power, it was at last clear to the Party hierarchy that younger leadership was needed, and Gorbachev became General Secretary. He was ready to make long overdue reforms in the Soviet system.

For six years, Gorbachev carried off a delicate balancing act, forcing reforms on a recalcitrant old guard, while trying to contain the demand for change from radical reformers within and without the Communist Party. He permitted an unprecedented freedom of expression in the USSR and ended the disastrous Soviet military involvement in Afghanistan. By 1989, the demand for reform had spread to the Soviet satellite states of Central Europe. Gorbachev notified the Communist leaders of those countries that he would not intervene militarily to keep them in power as his predecessors had done. Without the support of the Red Army, these dictatorships were quickly forced to yield to their democratic opposition, and Gorbachev began the withdrawal of the remaining Soviet forces from Central Europe. In 1990, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his foreign policy initiatives.

Gorbachev continued to press for democratization in the Soviet Union and permitted free elections in Russia and the other republics of the Soviet Union. He survived an attempted coup by Communist hardliners in 1991 but relinquished office after the elected presidents of the constituent republics undertook to replace the old Soviet Union with a Confederation of Independent States.

Since leaving office, he has continued to advocate the development of private ownership in a market economy, and the nonviolent resolution of conflicts in a democratic society. In 1992 he inaugurated the International Foundation for Socio-Economic and Political Studies, known as the Gorbachev Foundation. Gorbachev has served as president of the organization since its founding. The following year, he inaugurated a new environmental organization, Green Cross International.

His wife, Raisa Gorbachev, died of leukemia in 1999. Her presence in her husband’s life was unprecedented in the Soviet experience. She appeared with him in public at home and abroad, served as his eyes and ears on her travels, and was one of his closest advisors. Mrs. Gorbachev’s activities were readily accepted in the West, but they were the subject of much criticism in the Soviet Union. They overcame a rigidly patriarchal code of Russian behavior in which women were rarely seen and almost never heard. Mikhail Gorbachev wrote in his memoirs, “We were bound first by our marriage, but also our common views of life. We both preached the principle of equality.” It was a long journey from her humble origins. Raisa Gorbachev was the daughter of a Ukrainian railway engineer. Mikhail Gorbachev met her while they were both students at the elite Moscow State University and they married in September 1953. Raisa gave birth to their only child, daughter Irina, in 1957. They have two granddaughters, Ksenia and Anastasia, and one great-granddaughter, Aleksandra.

In the 1990s, Gorbachev was a vocal critic of Russian President Boris Yeltsin’s privatization policies, and of Yeltsin’s efforts to expand the powers of the presidency. Gorbachev himself mounted an unsuccessful campaign for president of Russia in 1996. He founded a new political movement, the Social Democratic Party of Russia, in 2001, but it won few adherents. Gorbachev stepped down as head of the Party in 2004 and it was later decertified by the national government. Gorbachev formed a new faction, the Union of Social Democrats, in 2007, but within a year he set this aside and joined billionaire financier Alexander Lebedev in founding the Independent Democratic Party.

Gorbachev owns a part interest in the newspaper Novaya Gazeta, which generally opposes the ruling party of President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev, but he has expressed support for some of Medvedev’s foreign policy positions, including military action in South Ossetia. Gorbachev has opposed American foreign policy in a number of areas, such as intervention in the former Yugoslavia, as well as the 2003 invasion of Iraq. He has also been critical of U.S. economic policy and the role of the International Monetary Fund.

In 2009, Gorbachev joined his former adversary Lech Walesa and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in a public observance of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Although he has not played a major role in post-Soviet Russian politics, Mikhail Gorbachev’s role in the historic transformation of the former Soviet Union has won him recognition around the world as one of the most influential statesmen of the 20th century.

“What would you call it when the country is being ruled by old men who keep dropping dead, and the country is left without normal leadership?”

In only three years, the Soviet Union lost three leaders: Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko. One after another, the men chosen as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR fell dead, and one of the world’s two super powers looked lost and rudderless, mired in a hopeless war in Afghanistan, locked in a ruinous arms race with the United States, occupying half of Europe but unable to supply the basic needs of its own people.

A new leader, the youngest man to lead the Soviet Union since the 1920s, promised change. The stated principles of Mikhail Gorbachev’s administration were “glasnost” and “perestroika,” or openness and restructuring, words which became known throughout the world. Gorbachev allowed a freedom of expression Russia and many other states of the Soviet Union had not known in their long history.

The rise of democracy in Russia and the end of the Cold War division of Europe are the direct result of Mikhail Gorbachev’s extraordinary term of office as leader of the Soviet Union.

When you initiated your reform policies — glasnost and perestroika — did you anticipate where this would lead? Did you realize how dangerous it might be?

Mikhail Gorbachev: Yes, yes, yes. From the very beginning.

I had before me the experience of Khrushchev, Kosygin, and many other people who were punished for their initiative. They were seen as people who were unreliable, who undermined the system. They were disposed of. You also have to understand that I was very familiar with what our country was really like, that you could expect anything at all from it.

Furthermore, when I began to translate political reforms from statutes and slogans into a real process of political reform such as free elections, a parliamentary system, independent courts and so on — the separation of executive and legislative power — these were enormous changes. It was then that we began to set term limits — stipulated by law — for holding an official post, so ambitious people wouldn’t usurp their positions for decades.

A student in Japan once asked me, “President, democracy is all very well. You were elected; you introduced free elections and everything, but at the next election you might not be elected and you will lose.” I told her, “But you see, even then I will not lose, because there will have been free elections and that is the result of what I have been trying to achieve.” I said, “If I win a free election then I will have a double victory. If I lose then there will only be one victory, but democracy will exist and that is the main thing.” For this reason, when they ask me nowadays how I feel, after all that has happened, I say, “Of course it did turn out that the very moment we were supposed to go further in reforming the Soviet Union, the Party and the economy, perestroika was interrupted, but what it accomplished, and what processes and tendencies it laid down — that is an enormous victory.”

What do you think made you, of all the Soviet leaders, open to change, open to reform, both within the country and in the Soviet Union’s relations with the world?

Mikhail Gorbachev: Well, after all, I did come from a different generation.

We, our generation, were not associated with the repression. Moreover, we ourselves were aware of the repression, and that left its mark on us, because ours was an educated generation, a generation that knew its own value, and was capable of thinking and analyzing. When we found ourselves active participants in life, in work, and in politics, then we began to see a great deal and see it clearly. Little by little there came the awareness that in this country, this society, this system, no matter how hard we tried, no matter how sincere our convictions were, very little good could be achieved. Therefore the system had to be changed.

But this happened when we were adults. Now if you are talking about me in particular, I think that my political career was successful.

After the university, in 1955, I became a professional politician, and in just 15 years I was already a member of the Central Committee and the head of a large region, the equivalent of a governor. I governed this large region for almost nine years. And, evidently I distinguished myself in some way so that they invited me to come to work for Brezhnev in the Politburo, the Central Committee. So I found myself at that place at the time when society was growing ripe for — or really, had already given rise to — the desire and the expectation for change. Especially since this occurred during a three-year period when we lost three General Secretaries, Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko. The whole country was simply in some kind of — what would you call it when the country is being ruled by old men who keep dropping dead, and the country is left without normal leadership? This was the mood in society. Plus the experience that I already had. After all, I had worked for seven years in the Politburo before I got to be General Secretary. Without that it would be unlikely that I would have gotten to be the head of a country like ours.

It was, aside from everything else, a lucky combination of circumstances.

Surely there were other leaders and other interests that would not have had the same results in the Soviet Union. What was there about your upbringing, your background, your experience that led you to be the man?

Mikhail Gorbachev: I don’t know, but if you mean were there other candidates, then there certainly were. Whether they were better or worse, I do not know. But my chances turned out to be better.

I was relatively young, the youngest of the lot, actually, and I was a man with a modern education who already had a great deal of experience working independently. At the beginning, that was important, that was significant. Also, the fact that… I was given the post of General Secretary, tantamount to being a Tsar, and did not get drunk on my own power, but instead began to transform it. That already was the result of my democratic convictions. I had had them ever since I was young, and they became my defining characteristic, my credo: devotion to democracy, respect for the worth of the individual. But the system had suppressed all that; it did not allow an individual the freedom to actualize himself. I did not accept this.

Evidently, my reactions were the reactions of a member of the milieu to which I belonged and which I considered my own, that of the democratic, progressive, thinking intelligentsia, with a critical attitude toward all that. This was the source of it.

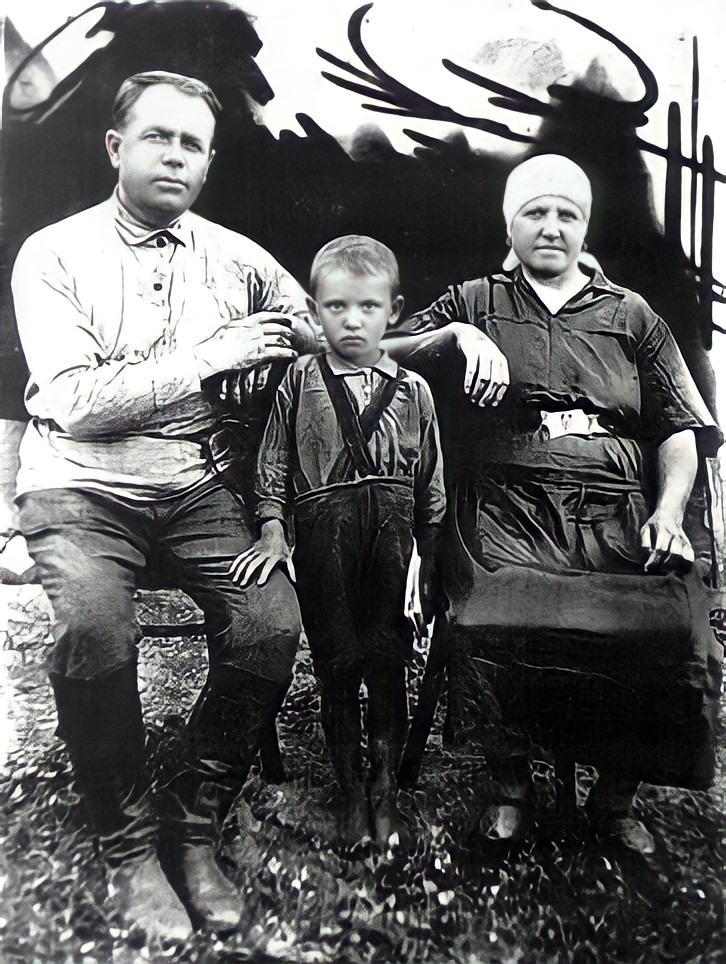

May we ask you to remember what it was like growing up in a Russian village, in the countryside in the 1930s?

Mikhail Gorbachev: What I remember is a pre-war village, and the life of the peasants, since I myself come from peasant stock. It was a very poor village, the housing was very poor, and so were our clothes, and there was a great deal of work, and even more anxiety. So this was a very serious life experience for children. And then of course there was the war. We lived on the German-occupied territory. That too is part of my memory. The front passed through our village, and then was pulled back, and then moved forward again, and this was all happening right in front of our eyes, the eyes of the children. Thus, you see, I belong to the so-called “children of the war” generation. The war left a heavy mark on us, a painful mark. This is permanent, and this is what determined a lot of things in my life.

Because of growing up in a peasant family, and my experience of life and the war — which I saw myself, all this blood and destruction, horrible destruction — all this had great significance. This was all when I was a child, and yet that whole period is as clear as if it happened yesterday. I have forgotten a great deal of what happened in my life, but all that hasn’t left me. At that time, I began to feel the desire for something more; I wanted to do something to make things better. This was unconscious; it was just something that was brewing inside of me, without my really being aware of it. So, when my father said, “If you want, why don’t you go and try to get an education. If not, you can go on working the land with me.” And I said, “I want to try.” I ended up at the university, and this was a completely different world, the start of a whole new life. The university was like a door opening up on the whole world. For a young man thirsting for knowledge — coming from the sticks, from the back of beyond, coming to the capital, to Moscow, to the university — it was cataclysmic.

You worked your way through the ranks of the Young Communists League, the Komsomol. What led you in that direction?

Mikhail Gorbachev: I guess that by nature I am one of those people whom nature has given what they call leadership qualities. This perhaps is too strong a word — leadership qualities. What I mean is that among my peers I was always the one who took charge. I liked being the boss, but the main thing was my friends trusted me, and that’s why I say that most likely such qualities were innate in me. I always wanted to do something, accomplish something, or take the initiative. In school they kept choosing me to be the leader. I joined the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) while the war was still going on. That was really where it all started. Yet of course…

There were many such people with initiative in the Soviet Union, very many, and they wanted to find ways for self-actualization. There was the Party, there was Komsomol, and naturally, since the Party was actually the only party available, everyone joined it. There was only one Party, everyone joined the same party. Also, I must confess, I remember that at the time the Party’s slogans appealed to me, they made quite an impression on me. It was very seductive, very attractive, and I took it all on faith. A lot of time still had to pass before I began to understand what the purpose and nature of the Party slogans really were, and what real life was, and what the Party meant for the country. And that the Party, which I had joined, itself badly needed to be reformed and reoriented toward democracy. And through this, the country could begin to gain some freedom. That came later, but it all started with the desire to do something and show initiative. That was what led many good people to join the Komsomol and the Party.

How did someone become critical, questioning, in the Soviet system you grew up in?

Mikhail Gorbachev: That’s a whole research project, a dissertation.

Confrontation with life, that is what causes a person to adopt a critical position. But for that to happen, you yourself have got to have a certain amount of resources and vision, confidence in democracy, devotion to freedom. If you simply bend in the wind and cave in under the pressure of circumstance, you will accept things as they are. And in that case you do not develop a position of protest and criticism, but you will simply become like many others before you. Even now in Russia we have the same problem. It isn’t so easy to give up the inheritance we received from Stalinism and Neo-Stalinism, when people were turned into cogs in the wheel, and those in power made all the decisions for them.

My position was as follows: through democracy, through glasnost, compel people, rouse people to speak for themselves, analyze, and decide for themselves what is to be done. That was the main thing that drove me. Of course I also saw that the country was breaking down, that it was beginning to lag behind. It could not react appropriately to the challenges of the technological revolution; it was not flexible, because the people were permitted no initiative, no freedom. The entrepreneurs were not permitted this, nor was anyone else: teachers, physicians, engineers, scientists. Everything was under control; everything was in gridlock or stagnant. That’s what I saw.

One can and must understand that one cannot do or know everything. Even God, who created us, doesn’t lead us through life by the hand, but wishes and hopes that we will think and act in life in accordance with His commandments and expectations, and to rouse people to take the initiative, to have faith in themselves, and the desire to live as their conscience dictates. That means to awaken great feelings, which cannot help but make life into something completely different. You will say, “But that’s Utopia! Could it really be that Gorbachev was filled with such Utopian ideas, when he undertook such realistic actions, the overhaul of the Soviet system?” To which I would give you a very short answer. Idealists make the world go ’round, since everything starts with ideas. Yes, ideas! Everything comes from them and everything begins there.

Thank you very much, Mr. President.