I can say this in all honesty, it never crossed my mind that I would fail.

Robert Lefkowitz was born in New York City and raised in the borough of the Bronx in a high-rise apartment complex known as Parkchester. All four of his grandparents were Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. His father, Max, was an accountant in the garment industry; his mother, Rose, was an elementary school teacher who set high standards of academic accomplishment for her only child. Max Lefkowitz was mathematically gifted and enjoyed teaching his son mathematical tricks and games. A precocious reader, the young Robert was excited by Paul de Kruif’s The Microbe Hunters and enjoyed Arrowsmith, Sinclair Lewis’s tale of an idealistic physician. The family doctor became his role model, and he decided at an early age that he wanted to be a physician. An active Boy Scout, he also enjoyed experimenting with a chemistry set and a microscope, playing stickball in the street, and following the fortunes of the New York Yankees. After attending his local elementary and junior high schools, he won admission to the famed Bronx High School of Science, a public school that admits students on the basis of a competitive examination.

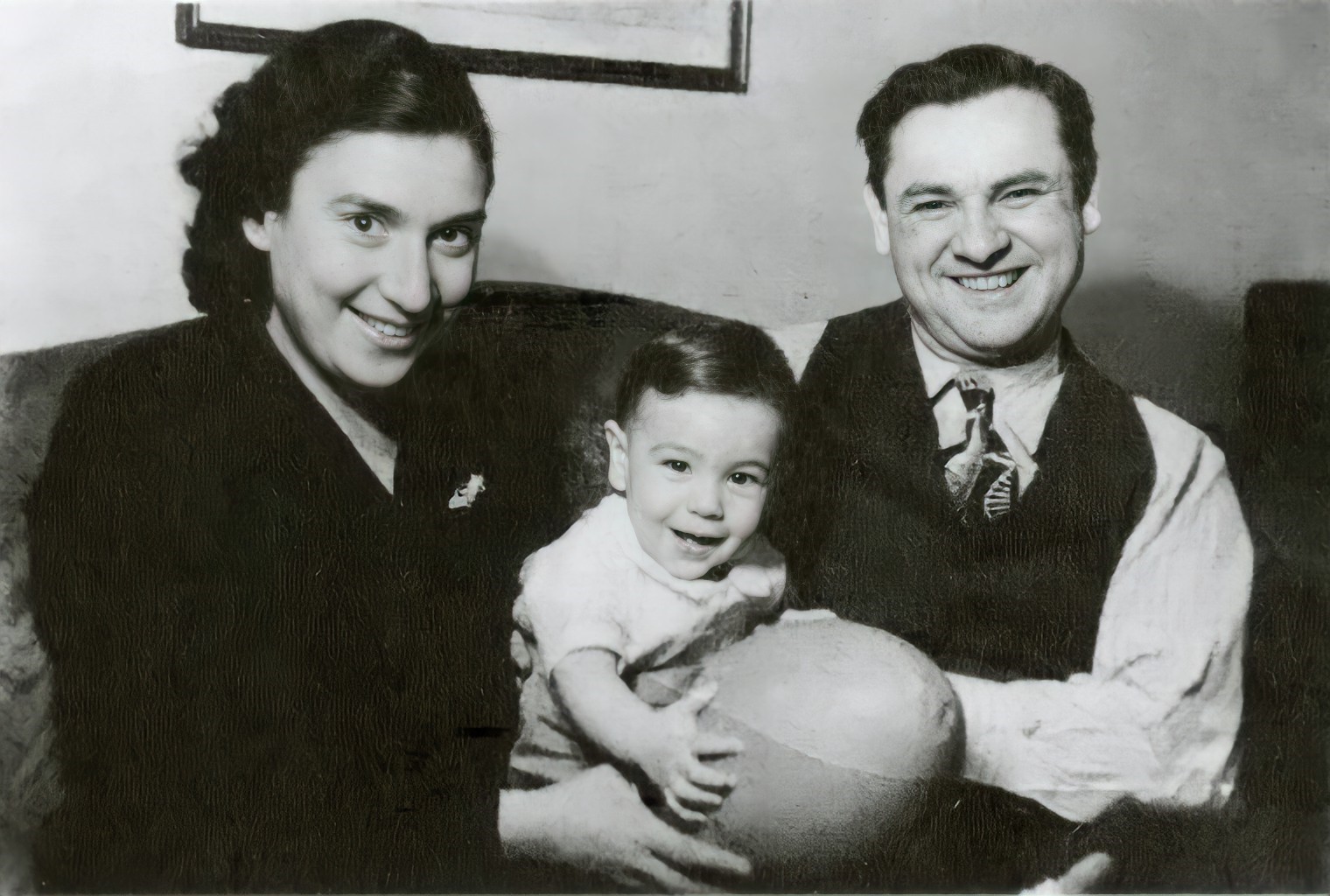

Then, as now, academic standards at Bronx Science were high; Lefkowitz would become the eighth graduate of the school to receive a Nobel Prize. He graduated in 1959 at the age of 16 and entered Columbia University. Although he enjoyed his classes in organic and physical chemistry, as well as an advanced seminar in biochemistry, he remained committed to his goal of studying medicine. He completed his bachelor’s degree at age 19 and entered Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. After his first year of medical school, he married Arna Gornstein and the couple quickly started a family. In the middle of his medical studies, Robert Lefkowitz became a father at age 21. Despite the demands of his family life, Lefkowitz thrived in medical school, just as he had in every other academic setting.

Graduating from medical school in 1966, he undertook an internship at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. For two years, he endured the grueling schedule expected of medical interns in that era, often going without sleep for two days and nights while on call at the hospital. In 1968, America’s military involvement in Vietnam was at its peak, and all young physicians were subject to compulsory military service. One avenue open to doctors with exceptional academic credentials was a commission in the United States Public Health Service. Lefkowitz received one of the coveted commissions and relocated, with his growing family, to work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C. Medical research in the United States benefited enormously from the influx of talented young medical scientists in the Public Health Service during those years. Dr. Lefkowitz arrived at NIH as new discoveries were disclosing the interaction of hormones and enzymes in the cells of living organisms. Many researchers discussed the possibility that individual receptor molecules somewhere in the cell membrane were responsible for detecting the presence of hormones such as adrenaline, histamine, dopamine and serotonin, but what or where these receptors could be found, or if they even existed, remained unknown.

For his public health research project, Lefkowitz attempted to tag the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) with a radioactive isotope of iodine to track its progress through a plasma membrane derived from a mouse tumor. Lefkowitz was inexperienced in laboratory research and the first year of his work failed to produce the hoped-for result. Until this point, Lefkowitz had excelled at every intellectual challenge, and he found the routine setbacks of scientific research deeply disturbing. At the end of the year, Lefkowitz’s father, Max, died at the age of 63. Robert Lefkowitz had enjoyed a close, supportive relationship with his father, and this loss, coming in a period of intense professional frustration, contributed to Lefkowitz’s feeling of defeat.

Looking forward to the end of his term with the Public Health Service, Lefkowitz planned to undertake a residency at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. As he began his last year at NIH, he enjoyed a major breakthrough in the laboratory. He had at last developed the binding assay for ACTH he had sought, enabling researchers to observe the movement of the hormone through the plasma membrane. He published his first scientific papers and presented his findings at national medical conferences.

After fulfilling his commitment to the Public Health Service, Dr. Lefkowitz moved to Boston with his family, as planned, to take up his residency at Massachusetts General. Although he enjoyed the return to clinical practice, he soon missed the atmosphere of the laboratory and the pursuit of the unknown. After the first six months of residency, he was expected to choose an area of clinical practice for further study and undertake two years of additional training in cardiology, but he broke with the hospital’s rules for resident physicians and took a research position in the hospital’s cardiology laboratory.

Still fascinated by the possibility of discovering the elusive receptors he had first considered at NIH, he saw the potential for a whole new field of research. The first beta blocker had recently been approved for clinical use in the United States. Beta blockers (also known as “beta adrenergic antagonists”) interfere with the cell’s ability to respond to adrenaline, but the mechanism by which they accomplish this was not understood. Lefkowitz suspected that these drugs prevent adrenaline from interacting with a specific protein in the cell wall. In 1971, he began his hunt for this hypothetical “adrenergic receptor.” Finding such receptors — and determining their composition, properties and function — would occupy him for the next 40 years.

Applying the radioactive techniques he had pioneered at NIH, Lefkowitz attempted the receptor for adrenaline, but developing the necessary research techniques and testing hundreds of thousands of possible receptor molecules would take many more years. Lefkowitz had to divide his time between his research and his ongoing duties as a medical resident and cardiology fellow at Massachusetts General. The fourth of his five children was born in 1971, and Lefkowitz took a number of part-time jobs on the side to support his family, working as an emergency room physician, as a medical examiner for insurance companies, and as team physician for a high school football team.

Although his research did not yield immediate identification of the adrenergic receptor, Lefkowitz continued to publish other discoveries he was making along the way. By 1973, he had completed his fellowship in Boston and accepted an appointment as associate professor in charge of a new program in molecular cardiology at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

After his first year at Duke, Lefkowitz and his postdoctoral fellow Marc Caron developed the binding assays for adrenergic receptors. Now that the receptors had been found, direct study of them could proceed. In 1976, Dr. Lefkowitz was selected as an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). At the time, only 50 medical scientists in the world enjoyed the support of HHMI, which is given directly to the individual investigator, rather than to an institution or a specific project.

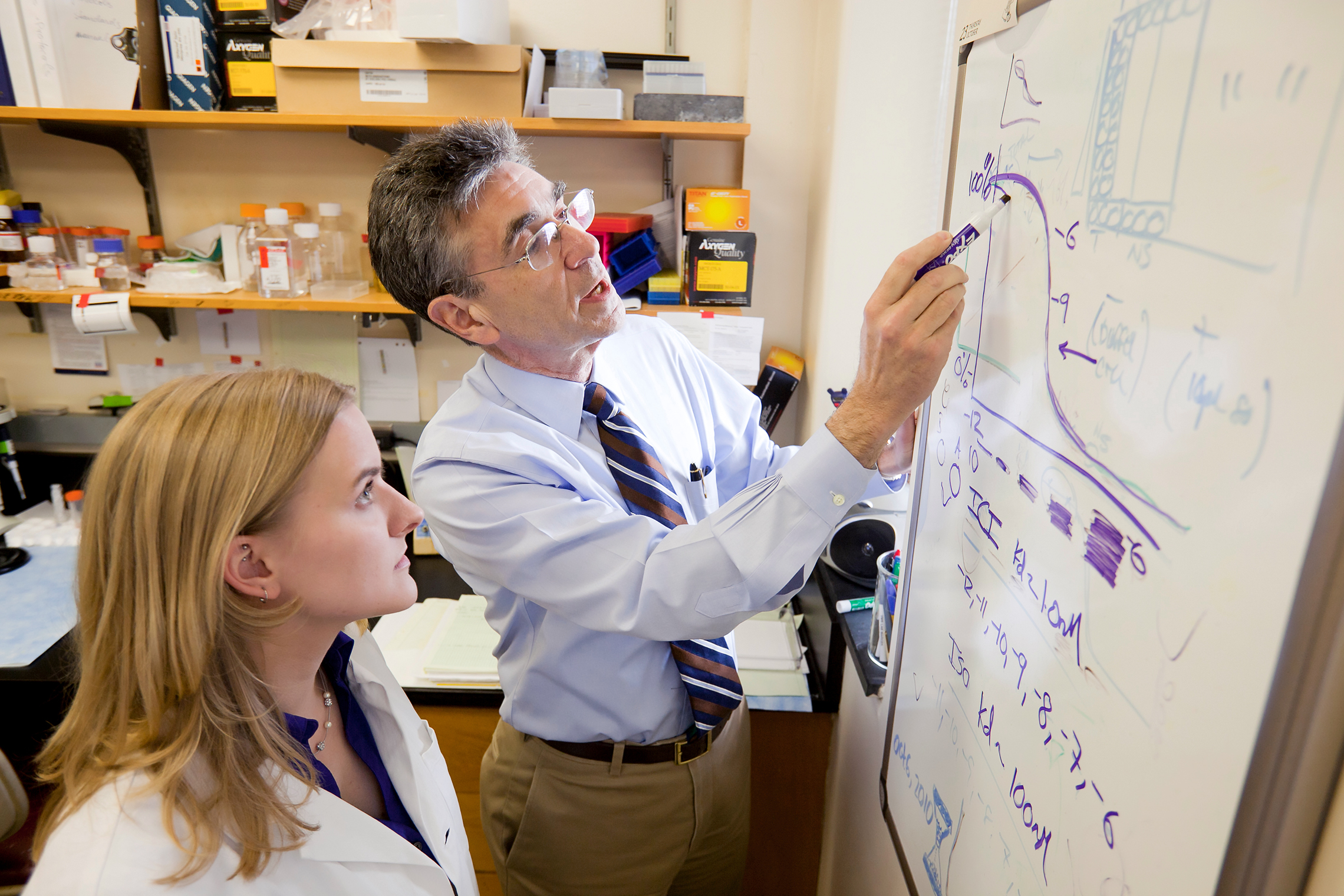

Over the next decade, Dr. Lefkowitz and a succession of dedicated graduate students and postdoctoral fellows developed new tools for detecting and analyzing the receptors he had discovered. Among the many exceptional young scientists trained by Dr. Lefkowitz, a particularly notable one arrived in 1984. Brian Kobilka stayed at Duke for five years before moving on to lead a laboratory of his own at Stanford University, where he would further develop the concepts he explored with Dr. Lefkowitz.

The Lefkowitz laboratory made a huge breakthrough in 1986. Having isolated one “G Protein coupled receptor” (GPCR), Lefkowitz and his team were able to clone it and decode its complete sequence of amino acids. When they checked this sequence against the database of known DNA molecules, they found that it was nearly identical to rhodopsin, the molecule that registers light and allows the eye to see. If the receptor for light and this newly discovered receptor for adrenaline could be so similar, it suddenly seemed probable that the receptors for a large number of other hormones might be as well. Within a few years, they had discovered nearly a dozen such receptors. Today we can identify a family of roughly 1,000 different receptors in the human body. Mutations of some of these are known to cause both acquired and inherited diseases.

Dr. Lefkowitz’s discoveries have had the greatest impact on the development of new drugs. Nearly half of all prescription drugs are designed to engage the receptors that Lefkowitz identified. Beta blockers, antihistamines, ulcer drugs and others are used to treat a wide variety of disorders, including hypertension, angina, coronary disease, diabetes, anxiety and depression. Although Dr. Lefkowitz did not patent any of his early discoveries, he has founded a company called Trevena to develop a new class of drugs, based on his latest research.

Robert and Arna Lefkowitz had five children between 1964 and 1975. The marriage ended in divorce, and both partners have remarried; Robert Lefkowitz married Lynn Tilley in 1991. After years of working a relentlessly demanding schedule, Robert Lefkowitz was diagnosed with angina at age 50. There was a strong history of coronary artery disease in his family, and he has made a number of adjustments in his way of life. Since undergoing quadruple bypass surgery in 1994, he has managed his condition with medication and daily exercise, and by observing a vegetarian diet. In 2003, he discontinued teaching rounds and clinical work to focus entirely on research. That same year, 100 of his former students returned to Durham to celebrate his 60th birthday.

Today, Robert Lefkowitz is the James B. Duke Professor of Medicine and Professor of Biochemistry at the Duke University Medical Center. He is still an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). Although there are now more than 300 HHMI investigators, as of 2014, Dr. Lefkowitz was one of the two longest-serving investigators.

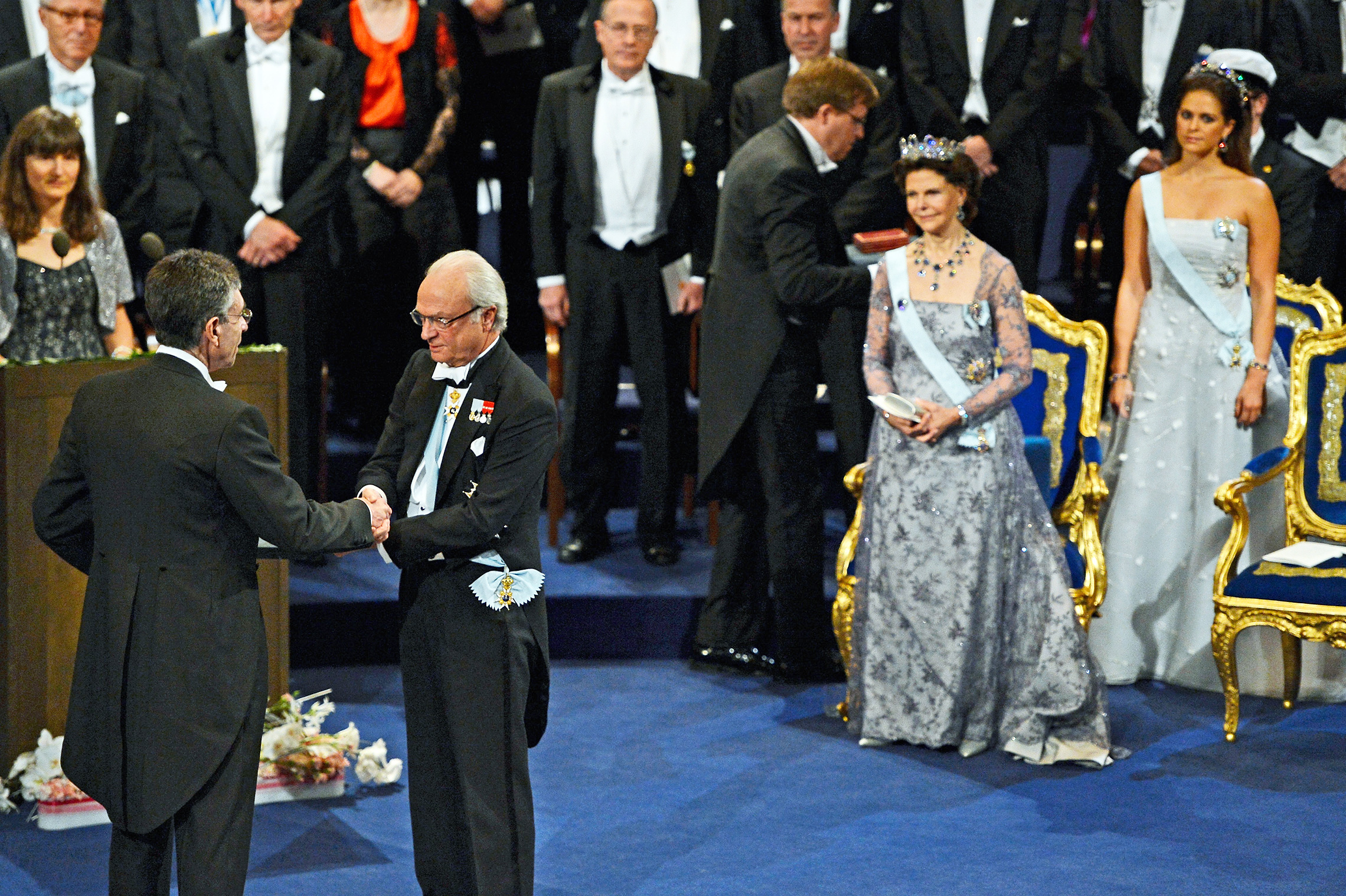

Dr. Lefkowitz has received almost every major award in American science, including the National Medal of Science and the Bristol-Myers Squibb Award, as well as honors from the American Heart Association, Canada’s Gairdner Foundation and the Grand Prix of the Institut de France. For a number of years his name had been mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. He was caught off guard when he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2012. The award was shared with his former student and longtime collaborator, Dr. Brian Kobilka of Stanford University. When he traveled to Stockholm, Sweden to accept the award, he was accompanied by his wife, Lynn, all five of his children and two of his five grandchildren. More than 40 of his former students flew to Stockholm at their own expense to celebrate the occasion.

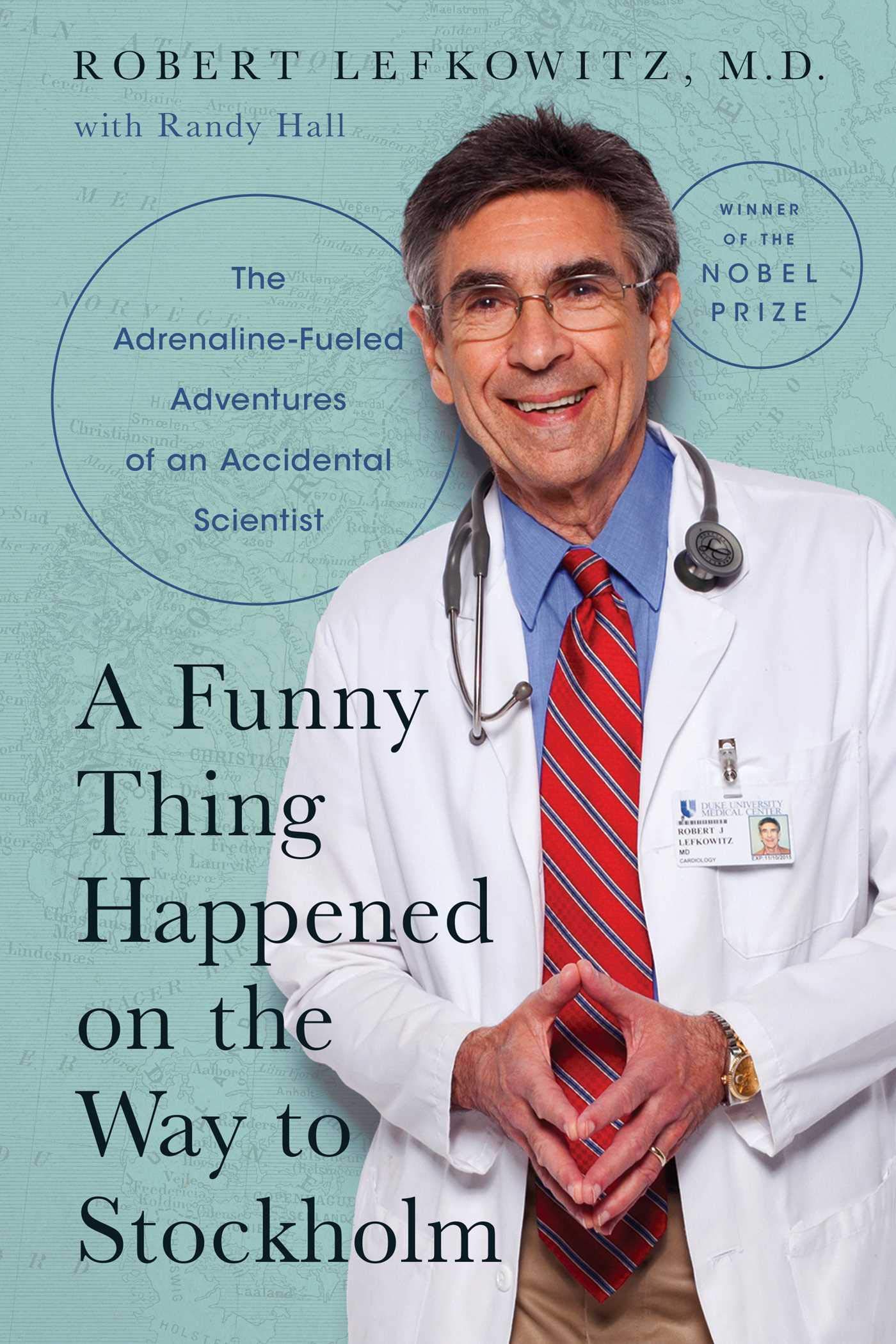

In 2021, Dr, Lewfowitz received enthusiastic reviews for his characteristically witty memoir, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Stockholm (The Adrenaline-Fueled Adventures of an Accidental Scientist). In his book, along with tales of his youth, education, and the discoveries that led to his Nobel Prize, Dr. Lefkowitz recalls memorable encounters at the 2014 and 2017 International Achievement Summits.

When Dr. Robert Lefkowitz began his research career in the late 1960s, it was already known that hormones such as adrenalin, histamine, dopamine and serotonin stimulate specific responses in the cells of human beings and other organisms. But the mechanism by which cells perceive and respond to these hormones was shrouded in mystery.

In 1969, Lefkowitz successfully attached a radioactive isotope of iodine to a form of the hormone ACTH (adrenocorticotrophic hormone), enabling him to demonstrate its receptor’s presence in cell membranes from an adrenal cortical tumor. Beginning in the early 1970s he began applying similar methodology to studying the receptors for adrenaline called adrenergic receptors. Over the next 15 years he would identify several different types of adrenergic receptors by utilizing these “radioligand binding techniques.” In 1986, he and his associates at Duke University Medical Center succeeded in cloning and sequencing the gene for one of these receptors and found that it responds to adrenaline much as receptors in the eye register light. He has since identified a superfamily of receptor proteins present in the outer membrane of cells.

Roughly half of all medications in use today depend on the action of the receptors Dr. Lefkowitz discovered; they are used to treat everything from diabetes to depression. His discovery has been recognized with nearly every honor in American science, as well as the 2012 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

You received the Nobel Prize for your work in receptor biology. When did you first become involved in this area of research?

Robert Lefkowitz: In 1968, when I went to the NIH, there was no receptor biology. And in fact, there was no consensus that these receptor molecules even existed. But my two mentors there thought they might, and I was given the project of trying to develop techniques to study a particular kind of receptor for a hormone. And I didn’t realize just how challenging — since I had no perspective — I didn’t realize just how challenging and daunting that assignment was. Nobody had ever done anything like that. And, as I said, for 18 months, I flailed and failed. But I did eventually meet with a modicum of success, and started to like it and saw the value in studying receptors. I could see a vision of where that might go, although in retrospect, I had no idea just how far it could go. So when I set up my own laboratory at Duke, I decided to study receptors. But since I was now a cardiovascular physician, I chose very deliberately to study something called adrenergic receptors, which means receptors for adrenaline. These are the targets of beta blockers, which are commonly used drugs. In retrospect, that turned out to be a very felicitous choice. Of course, I had no way of knowing that then. So that’s how I got interested in it in the first place, and then I just kind of ran with it.

So at the time, there wasn’t even evidence that these receptors existed?

Robert Lefkowitz: Correct.

That’s a remarkably courageous act, but also a very creative one, to try and open up a whole new area of biology.

Robert Lefkowitz: Exactly. In retrospect, yes. At that moment, I didn’t see it that way. I often tell people that if I knew then what I know now, there’s no way I would have done this, because it was so difficult as it turned out.

I can tell you this in all honesty. It never crossed my mind that I would fail. And I don’t know why that is. It almost seems delusional. Because there was no proof that these things even existed. And yet it was raw intuition. It just seemed to me, of course they exist. How else could it all work? And you know, I didn’t have a Ph.D. I was not a biochemist. I wasn’t anything. I was a physician. So I was kind of self-taught over the next few years. I gathered students and post-docs together and off we rode into the night to try to figure it all out. I talk about sometimes the chutzpah of youth. It was totally chutzpahdich, as we say in Yiddish. It was just filled with chutzpah — brazen gall that you would think you could do that. But you know, in the end it worked. And exactly why, I can’t say. I guess it was meant to be.

You had to trust that instinct.

Robert Lefkowitz: Yes. It’s not only that I was not filled with self-doubt. And it was not that I was an arrogant person. Even with all the failure that I had had, and with all the failure that would come my way over the next 15-20 years, it just seemed to me, it was always a question of when — not if — things would work.

You have to be very patient as a research scientist.

Robert Lefkowitz: You have to have a huge tolerance for frustration and failure, which I do not innately have. Just ask my wife. I have no patience with failure. So how I survived it all, I don’t really know.

How did you go about proving the existence of this receptor, and why is it so important in physiology?

Robert Lefkowitz: Receptors are molecules, we now know, on cells, with which hormones and drugs interact to begin their biological actions. To give you a specific example, consider adrenaline, also known as epinephrine. Let’s say we have a patient with asthma and their airways are constricted. They can’t breathe. We give them adrenaline and the airways relax because of the smooth muscle in their airways relaxes when the adrenaline works on it. How does the adrenaline know to work on that, and to stimulate the heart, rather than to work on your nose or your retina or something like that? Well, the answer is, and what seemed obvious to me, is there must be molecules on the cells that the adrenaline would bind to, much like a key interacts with a lock, where the key would be the adrenaline, but it could be any hormone by extension. And this mystical receptor I was looking for would be like a lock on the cell, and it would fit in, and the adrenaline would then do something to that lock, open it, and things would happen in the cell. That was the idea. So how to prove this? Well, at first, there was no way to even study it.

The first thing we had to do was find some way to study these things. So I used — again, it’s a relatively simple idea. The idea is simple. In practice, it’s very difficult. Which was to take molecules that I had reason to believe could interact with this receptor, like beta blockers, which had just been developed, and radioactively label them and use that radioactivity as a way of following the binding, the sticking interaction of that molecule to the receptor. And then with this radioactive probe stuck to it, now I could try to isolate it, following the radioactivity as a marker. And over a period of years, we got that to work for several receptors. Then we dissolved the cell membranes, plucked the receptors out. The receptors are very rare. So for example, for every two- or 300,000 protein molecules in the cell membrane, one of them would be this receptor. So the next job was to isolate this receptor, to get rid of the 199,999 that aren’t the receptor and just get receptor. Okay, yeah, exactly. Extraordinarily difficult work, but we succeeded in doing that and showed that this one isolated molecule could do the two things that a receptor would do. First, it could bind or interact with drugs that were known to interact with that receptor. And in a way that would be predicted by the physiology. That is, if I had three things that could work on that receptor and we knew from physiological experiments that, say, drug one was better than drug two was better than drug three, then my protein should bind drug one better than two better than three. Only there weren’t just three, there were dozens. So we could test that very rigorously. So that was the first criterion. The second criterion is that binding of a drug like adrenaline to this receptor, that that receptor could now do something — stimulate the cell to do stuff. Now that was even tougher. So we came up with methods where we found cells that didn’t have adrenaline receptors. How did we know they didn’t have them? Because they couldn’t bind these radioactive probes. But they did have the response machinery, okay. Because they had receptors for other things. And then we took these receptors and by techniques that we worked out, we were able to plug them back into the outside of these cells. And now the cells responded to adrenaline. So now I knew that this pure receptor molecule that I had could do both things that you’d expect a receptor to do, interact with something like adrenaline, and do something to the cell.

The next series of discoveries, after we had purified this receptor, was to do what’s called “cloning the gene.” Okay. That allows us, because of the work on DNA, which we’d been hearing a bit about at this meeting. And of course, by the ’80s this was the era when recombinant DNA was picking up steam. All based on Jim Watson and (Francis) Crick‘s original discovery — from, I guess, the ’60s — about DNA. So we were able to ultimately clone the gene for this one particular receptor and thereby deduce its complete amino acid sequence. And when we did that, we made a remarkable discovery. And the discovery was it looked just like another molecule. And that molecule is called rhodopsin, and rhodopsin is the molecule in the eye that allows you to see. And when we saw that — this was in 1986 — we realized immediately that, you know, I’ll bet there’s a huge family of receptors that all look like this. In a sense, rhodopsin is a light receptor, and it looked just like what’s called a beta adrenergic receptor, which was one of these adrenaline receptors that I was studying. I said, “If these two, so disparate in their function, look alike, what about receptors for histamine, serotonin, dopamine? You name it. I bet they all look alike.” So using the techniques that we had developed, very quickly over the next few years, we were able to get the genes for about 10 or 12 of these different receptors. And they all looked the same. I mean, they had distinct sequences, very close though. I mean, you might have 60 to 70 percent of all the amino acids would be the same. But enough were different that they did different things.

Meanwhile, all these technologies were being adapted by the drug companies. So the pace of drug discovery increased dramatically, because they went from testing drugs in animals to being able to use the isolated genes that we had and they could now find. And then it turned out that there were about 1,000 different members of this family, not just rhodopsin and the beta receptor and the others I mentioned, but the smell receptors. It turned out the way we smell is by substances binding to receptors in our nose that look just like these. And then it turned out the way we taste bitter and sweet looks like that. So now, you had three of the five senses working that way. Well, it turns out this family of receptors regulate virtually all processes in animals. And today about half of all the drugs used clinically around the world target one or another of these receptors. I mean, things like beta blockers or antihistamines or opiates or you name it. So the work in the end had an impact far beyond what I could have imagined in 1970, when I was just beginning to do this.