Mr. Hume, can you tell us a little bit about your background? Where did you grow up?

John Hume: I grew up in Derry, of course, and it was — Derry was the worst example of Northern Ireland’s discrimination. Of course, the Unionist people, wishing to protect their heritage and their identity — and they’ve every right to do that, in my opinion because every society has diversity, and respect for diversity is central and essential. But my quarrel with their approach was, of course, their methodology. I called it their Afrikaner mind set. They held all power in their own hands in order to protect themselves, in order to ensure that the minority in Northern Ireland, which was the Catholic population, never became a majority, and that meant widespread discrimination in housing, in jobs and in voting rights. And of course, the worst example of that was the city of Derry, where I lived. Seventy percent of the population of Derry was from the Catholic community, largely Nationalist people who wanted Irish unity, and of course, 30 percent were the Protestant community, who were Unionists, but they governed the city and their system was known as gerrymander. They divided the city into three electoral wards, and in one ward there was 70 percent of the people, the Catholic population, and they elected eight representatives to the city council. And the other — there was two other districts which represented 30 percent of the population, and each of those districts elected six members. So the Unionists always had 12 to eight.

It was a kind of ghettoization, wasn’t it?

John Hume: Total ghettoization, because they were in charge of public housing, the local council, and they deliberately located people in a ghetto situation in order to ensure that they maintained control.

How did this affect your own family? Your father, we understand, was unemployed.

John Hume: Well, of course, this meant that there was discrimination not only in housing, but in jobs. And my father was unemployed, and of course, he was a very, very intelligent man and well known as that, because when I was child, growing up in our home, I would be sitting at the table doing my homework and my father would be sitting at the table, and people would be coming in from the district and around the city for him to write their letters because he was a copper plate handwriter, and he also knew the whole system inside out. So that, we suffered a lot from discrimination, but what happened — I was lucky in the sense that a new education system was introduced. It was introduced in Britain in 1944, but then eventually in Northern Ireland in 1947. In the first year of that, I passed the examination and got a scholarship to go to secondary school, and of course otherwise I would never have been educated.

Mr. Trimble, could you talk a little bit about your background, growing up?

David Trimble: I’m a Presbyterian, and grew up within that ambit. The Town of Bangor, Northern Ireland, was predominantly Presbyterian. In Northern Ireland, Presbyterian is associated with people of Scots background, Scots origin. Several centuries, 350 years ago, my ancestors came from Scotland to Northern Ireland. Now there’s been, obviously, over 300 years, a fair degree of intermarriage and mixing and all the rest, but you can still say, in Northern Ireland, that Presbyterianism is an indication of a background and a culture which is Scots. Being what you would call an Episcopalian is an indication of a background that would be predominantly English.

Did you think about public service and government when you were growing up?

David Trimble: I was interested in politics and would have taken a fair amount of interest, although my interest would have been in national politics rather than regional Northern Ireland politics. I remember, for example, staying up during the 1959 general election — which was won, of course, by Harold Macmillan — listening to the results. I would have been 14 at the time, and I would have been, in that sense, sort of — most of my years of school, people of the same age as myself wouldn’t have had the same interest in politics as myself, but I always was interested in politics.

What did you like reading, as a young person?

David Trimble: Like everybody at that age, I read an awful lot of pulp fiction. But at the same time, I also read quite a bit of history and read that as much for pleasure as part of a curriculum.

Any particular favorites that you can remember, favorite authors from that time?

David Trimble: There is one I do remember. It was a biography of King John, written by the chap who, at that time, was the main professor of history at Queens University. The thing that I liked about the book was that it didn’t follow the sort of traditional “bad King John” approach. It actually dealt with the times of John, and of course, people remember John in terms of Magna Carta and all the rest of it, but it was quite interesting to me to discover that John, when he was Lord of Ireland, had come right up to the other side of Belfast Lough, and had actually assaulted and carried Carrickfergus Castle, after a four-day siege and assault, which was quite remarkable because the castle — the Carrickfergus Castle which is still intact — it was quite a considerable fortification. It was the seat of the Norman barons of Ulster, and the Earl of Ulster at that time had been in revolt against King John. And, he was actually noted for these lightning military moves, extremely successful ones. Now, I mind you, he came unstuck a number of other times as well. But, what I liked about that book is it actually challenged the received view in terms of the review that we had received and found in, as it were, the school text, the history text. And, that I find interesting, and again, of course, one finds that again and again in life, that the received wisdom is sometimes —very often — right, but at the same time, you can have situations where a view develops about a particular person and then you find, when you look a bit more closely, that the reality is otherwise.

The author was Louis Warren, W.L. Warren. King John was his first book, and then he wrote another very good book on Henry II, and many other books, as well. I had the pleasure of meeting him and getting to know him quite well when I joined the staff at Queens University.

Mr. Trimble, could you talk a little bit about your early political life? First of all, how did you experience the Troubles yourself?

David Trimble: Well, Bangor was a town in the north area of Northern Ireland which has not, in fact, been directly affected by the Troubles to any great extent. There have been effects, but not greatly. What we call “the Troubles” in Northern Ireland have been actually quite localized in their impact, in the sense that there are particular localities that have suffered very badly, North Belfast, for example, which has had a very bad impact in terms of the number of fatalities that have occurred. Although in terms of number of fatalities per population, the worst affected areas have been in West Tyrone, particularly around the small village of Castlederg. So you’ve got particular localities like that which have been badly affected. The disturbance to the political situation generally, yes, that has been a problem.

One thing that particularly influenced me was that a lot of the initial difficulties arose around the City of Londonderry and a number of claims — political claims — were made about the City of Londonderry and particularly the local council. Now it just so happened that a relative of mine had been, in the late ’50s, mayor in Londonderry. When I heard people talk about —late ’50s, early ’60s — I heard people talk about what the local authority was alleged to have done in Londonderry, and I said, “Well, now, that can’t have been Jack, because I knew Jack to be a person of irreproachable character.” And I said, “What I’m hearing can’t be right.” That, if you like, ties up with my attitude to the history of John. “What I’m hearing can’t be right.” When I looked more closely at the circumstance, I thought it wasn’t entirely right, in fact, with regard to him personally, not right at all; but with regard to the situation, not a fair account, and that engaged me, at that sense. In terms of the violence of the Troubles, no, I can’t say that that affected me directly, although like everybody in Northern Ireland, I have had friends who have been murdered. I have close friends who have been murdered, although those came at a later stage. That’s in the mid 1970s, after the Troubles had been underway for some time before that happened, I had that experience.

Mr. Hume, how did your family survive? How did they support themselves?

John Hume: My father was unemployed and I was the eldest of seven children. We were very poor. And when you ask how did we support ourselves, the only funding that we had was unemployment payments. In this city, at that time, of course, most men were unemployed.

The women worked, because the city was the center of the shirt industry. But my mother used to work at home at night. She didn’t work during the day because she was rearing seven children, but at nighttime, she would do some outside work for the shirt factories. We grew up, but we were poor. When I was at school, one of the things I did, I delivered newspapers at night to earn some money around the district. But that was a very common situation in the Derry of those days, and most Catholics grew up in that way.

In my opinion, what changed the situation eventually — and, of course, it took a lot of time to change it, things like that don’t change in a week or a fortnight — was the new educational system. That, for the first time, our population, particularly — because up to then, if you were from a poor background, you couldn’t go to higher education, because your parents couldn’t afford it. I got a scholarship to go to secondary school, and then at the end of my secondary school period, I got a scholarship to go to university.

Mr. Trimble, what did your dad do?

David Trimble: My father was a civil servant, fairly sort of middle ranking, low to middle ranking. He worked almost entirely in what was then called Administrative Labour, dealing with employment and unemployment issues. I remember, when I was very young, being taken to Belfast to what was commonly called “the Brew.” It was the Labor Exchange in Corporation Street, the main one in Belfast, where father worked.

Then latterly he worked on the programs to encourage investment in Northern Ireland. I remember one project that he worked in, in a fairly minor way, but was very pleased to be associated with. It was the very large development just outside Londonderry, which resulted in a major U.S. firm coming. In order to get that firm to come, the Northern Ireland government had to build a power station, and also a power station at Coolkeeragh, and then also provide its own docking arrangements.

A major jetty was built and all the rest, and that was just simply to get a very large U.S. textile firm to come. People were so keen to get investment. In those days, there was quite significant unemployment in Northern Ireland, and that had been the general pattern in Northern Ireland for many, many years.

What kind of school did you go to, Mr. Trimble?

David Trimble: I went to the local schools, the local state primary school, and then to the local grammar school. A secondary school, which technically was an independent school, it was not part of the state educational system. I went to it simply because it was the nearest school.

What kind of student were you?

David Trimble: Variable. The only thing I shall talk about is my sporting achievements at school. My primary sporting achievement at school was that I dodged games for two complete years and was well through the third year before they discovered that I had completely avoided all games. That, I think, is one of the achievements I had at school that I look back on with particular pride.

How did you manage that?

David Trimble: The school’s playing pitches were physically remote from the school. They weren’t actually on the same site as the school. So by virtue of not turning up on the first day, en route from the school to the playing pitches, there was the library, and I sort of dropped off in the library and spent my time. I mean the Carnegie Library in Bangor, which served the town as a whole. I would spend my time in the library. I didn’t get on the sports master’s roll, so he didn’t notice my absence.

In the U.S. we call that ditching class.

David Trimble: Well there you are.

What person or persons most inspired you growing up?

David Trimble: Every child growing up will look to their parents, my mother and my father. My grandmother lived with us. I picked up quite a bit of family lore and history from her, which was interesting. Those are, obviously, big influences. I think every individual is influenced primarily by the home, and then you look to the wider community that you’re growing up within, church, local community, school. These are the influences that everybody has. Some individuals might stand out because of one thing or another, but whether one’s perception as a child of what was important or not is accurate, I don’t know.

Mr. Hume, how did you become involved in politics?

John Hume: When I come home from university, of course, I thought that I had a duty to help those that weren’t as lucky as I was. And, the first thing I did was not — I wasn’t getting involved in politics, because the politics of those days was basically flag-waving and I had always felt politics should be about the living standards of people. But, when I come home, I wasn’t interested in politics in those days, but I was interested in helping people, and I got involved in the Foundation of the Credit Union movement. And, of all the things I’ve been doing, it’s the thing I’m proudest of because no movement has done more good for the people of Ireland, north and south, than the credit union movement.

What did the Credit Union do for people that wasn’t possible before?

John Hume: Before the arrival of the Credit Union, people who were from the poor background or a working class background couldn’t borrow from banks. Banks wouldn’t have them, and when they needed to borrow money for rearing their children and for furniture, et cetera, for normal things, then the methodology in those days was either from loan sharks or from pawn shops. And, of course, that meant that people were made poorer by all of that, particularly by the charge of loan sharks. So what the Credit Union movement did, of course, was not only help the ordinary people to have the true value of whatever their income was, but it helped local business, small business as well, because the money that would have left your city in loan charges remained and were spent. Therefore — I mean, when we started the Credit Union in those early days, the first few meetings, a few people joined, but very soon it spread rapidly. And today, that Credit Union — which I was involved in starting in 1960 — has 22,000 members, and has something over 40 million pounds in savings of the people. And of course, all over Ireland today, there’s 2.2 million members in Credit Union in a population of five million, and I am very proud that I was President of the Credit Union League of Ireland — of the whole of Ireland — when I was 27 years old.

Where did that kind of vision come from, Mr. Hume? Did you always have a feeling that you would be a leader in your world?

John Hume: I never thought in terms of being a leader. I thought very simply in terms of helping people. Having grown up as I grew up, I felt that anything I could do to help people I should do it, putting into practice normal attitudes to life. I think most human beings would help other people if they were able to do so.

You also made a very large difference in the lives of your countrymen by making it possible for more people to own their own homes. Could you tell us about that?

John Hume: When I was involved in Credit Union, I decided to do the same in housing, because housing discrimination was very widespread in our city. In working class districts, you had several families living together in the one house, and it was very difficult to get a house, because the politicians who controlled housing were doing so in a very discriminatory fashion.

What I got involved in was founding a housing association to build our own houses in the same manner as the Credit Union, but in the first year or so, we housed about 100 families. Then I put in a plan to build 700 houses, and the local politicians wouldn’t give us planning permission because it would upset the voting balance in their gerrymandered system, and that led me straight into politics, led me straight into the civil rights movement. And of course, in the 1960s, civil rights was very much in the international news because of the leadership of Martin Luther King in the United States, and that had a very major influence on people like myself, and we got involved in the civil rights movement, seeking equality of treatment for all sections of our people, and of course, my involvement in the civil rights movement led me straight into politics.

What was the connection between the civil rights movement in America and in Northern Ireland?

John Hume: In Northern Ireland, the civil rights movement was about discrimination and about equality of treatment. The civil rights movement in the United States was about the same thing, about equality of treatment for all sections of the people, and that is precisely what our movement was about.

The slogan that we had was “one man, one vote.” Today we would say “one person, one vote,” fair allocation of housing and fair allocation of jobs, and those were the three areas of discrimination. For example, in voting in those days, for example, at a local government level where all the discrimination took place, the only people who had votes were people who paid rates. So, if you grew up in your family, your mother and father would have votes because they paid the rent and rates, but you would have none, no vote, and of course, also, in those days, a limited company would have six votes. And, I remember a mayor of our city had 43 votes because he owned seven limited companies, which is 42 votes plus his own. So that was the civil rights that we were seeking: one person, one vote; fair allocation of housing; and fair allocation of jobs. Ordinary common sense and ordinary decency for our society, and that was our civil rights movement.

Mr. Trimble, you started your political career in the Vanguard party, didn’t you? What attracted you to them?

David Trimble: There was a considerable political upheaval in the early ’70s when the Troubles began. The established Unionist political leadership seemed to have difficulty in responding to it, and a number of parties came into existence, Dr. Paisley’s Democratic Unionist Party came into existence, other groupings came.

Vanguard was originally a “ginger group” within the mainstream Unionist party that evolved into a political party. What I found attractive about it was, unlike the others, it had a coherent response to the situation, and it seemed to me that it was doing some serious thinking about it. I joined Vanguard, and was elected as a Vanguard representative to the Constitutional Convention in 1975.

Unfortunately, although we came very close in 1975 to producing an agreement that would have resolved the situation and indeed, it was my own grouping, Vanguard, and particularly Bill Craig, with whom I was associated at that time, who took the initiative in bringing forward those proposals, which as I say, came very close to producing an agreement. That did not eventuate, and that actually politically destroyed Vanguard as an operation, the controversy over Bill Craig’s proposed coalition with the SDLP in 1975 led to basically, first, a split and then a collapse in Vanguard. Vanguard, at that stage, was part of a coalition that embodied the other main Unionist elements, too. And, I had the experience then — in early 1976 — of being expelled and found myself in the political wilderness, politically, for the ten years that followed that. But, I remember the particular experience in the early ’70s, how close we came to agreement, the areas where we had failed and thought a lot about it over the time, and it did mean that when political opportunities came for me later in the 1990s, that I had the experience of going through a major political upheaval and crisis comparable to that that we experienced in the late ’90s.

So in a sense, the setback was a very educational experience for you.

David Trimble: For a person who is involved in politics, politics is not a situation where you have a stable career. Anybody thinks in politics that they are going to have a career that builds in the way that a career in the civil service or in academia or even perhaps some business, they think that is going to happen, is wrong. Politics is very much a game of Snakes and Ladders, and I don’t think any politician can really regard themselves as being experienced and fully developed if they haven’t experienced failure, and I think failure is actually quite important in that sense. Seeing how other people react to you when you’ve had a failure is also quite educative.

“The Troubles” started around 1968, Mr. Hume. Can you talk a little bit about the beginning of that?

John Hume: We sought equality of treatment and civil rights, and of course that was refused and the civil rights movement was totally, as it was in the United States, totally non-violent and totally committed to non-violence, but quite often their marches would not be allowed by the government of the day in Northern Ireland. The marches would be stopped in the streets by the police of those days, and that, of course, created a lot of tension in the community as well. But as I say, the philosophy of the civil rights movement was certainly a strong philosophy of my own. I was very heavily inspired by people like Martin Luther King and by Mahatma Gandhi, and I quoted them quite a lot. In fact, in my political party, to this day, we always sing “We Shall Overcome.”

But as I say, I then got into politics. I stood for election and in that election, I sought a mandate to found a new political party based on social democratic philosophy. In other words, that we would deal with real politics, with housing, with jobs, with voting rights, and not into flag-waving politics, because in my belief that was a common ground, and if you work common ground together, that that would end the divisions in our society. First of all, if you had equality of treatment and then you started working in matters that affect all sections of the community, but of course, given the nature of our politics, it was very difficult to break down those barriers because the governing body insisted in standing by the old-style approach, and it has been a hard, long road.

The violence had broken out in both sides, but our philosophy as a party was very, very clear that there was two mentalities and both mentalities had to change. There was what I called the Afrikaner mind set of the Unionist politicians, which was holding all power in their own hands, and discriminating, and their objective was to protect their identity. We agreed that they had every right to protect their identity, but that their methodology should change because when you have widespread discrimination against a community, as we had in Northern Ireland, in the end, it’s bound to lead to conflict. And, our challenge to the change of the Unionist mind set was that — given their objective of protecting their identity, which we have no quarrel with — that given their geography and their numbers, the problem couldn’t be solved without them. Therefore, they should come to the table and reach an agreement that would protect their identity. Then in my own community, of course, what is called the Nationalist community, there was a mindset — not a majority mind set, but one that Ireland is — based on violence — and of course, that mind set I described as a territorial mind set: “Ireland is our land and you Unionists, Protestants, are a minority. Therefore you can’t stop us uniting.” Our challenge to that mind set, my challenge to that mind set, was that it is people that have rights, not territory. Without people, even Ireland is only a jungle, and when people are divided, victories are not solutions. When people are divided, the only solution is agreement.

Mr. Trimble, you joined the Ulster Unionist Party in the late 1970s. What was that party doing then? Why did it attract you?

David Trimble: Well, it was the mainstream Unionist party. In the problems that developed in the early 1970s, there was a certain degree of confusion and other parties developed, as did Vanguard. Vanguard grew out of the Ulster Unionist party and many people in Vanguard then ran into difficulties. The natural thing was to move back into the mainstream and work within that. It was the only viable political option in the late 1970s.

The Ulster Unionist Party, in the late 1970s, into the 1980s, was engaged in a very considerable internal debate about what the nature of its policy should be. I engaged in that a bit. I wasn’t entirely comfortable with the line that the leadership took in the 1980s, but nevertheless persisted and took part in the internal debate that was there. But, it was really only with the beginning of a talks process in 1991 that the opportunity came to change things, and, by then, I had found myself, a little bit to my surprise, a member of Parliament and returned as one of the party’s nine members of Parliament at Westminster. And so, when the opportunity came in 1991 with the beginning of the talks process, I was then finally in a position again to make some contribution politically.

Were there any equivocal feelings about taking a seat in Parliament, given the turbulence of the times?

David Trimble: The opportunity came by surprise. I found myself in a position of being the chairman of a constituency association, in fact, actually, the party leader’s constituent association, and there was always, in my mind, the possibility that at some point, he would be standing down, and there would be perhaps the opportunity of seeking the nomination in his seat. And then, tragically, the Member of Parliament of the neighboring constituency, he died in his early ’50s from cancer, quite unexpectedly and so consequently, an opportunity arose then and as I say, somewhat to my surprise, I was selected to contest that, and delighted to get the opportunity to do so. I mean, when the chance came to move back into the front line of politics, I had no hesitation in doing so.

Mr. Trimble, given what was going on in Northern Ireland, this was a very difficult position to take. You obviously had some confidence, even back then, that you could make a difference.

David Trimble: I was grateful for the opportunity to make a difference. The political violence really started in 1970-1971. The political difficulties start a little bit beyond that. In the mid ’70s, certainly, at the time of the Constitutional Convention, ’74-75, many people would have said of Northern Ireland that it’s obvious what the outcome is going to be.

You could sketch on the back of an envelope what the outcome was going to be. The detail would have to be negotiated. You would have to have the right opportunity to bring this about. You need to have the right combination of personalities. We nearly did it in ’75. Unfortunately, it took another 20 years before we had the right combination of circumstances and personalities. It’s important to bear in mind the difficulty of the situation. It was actually, to use someone else’s phrase, a low intensity situation.

The fatalities were actually lower than the fatalities that would have happened in any comparable city in the United States at any one time during that whole time. Through the 1970s and ’80s, Northern Ireland actually had a lower crime level than any comparable industrial area. It had political violence, but that was happening at a level where there wasn’t the same high level of intensity. And so consequently, you might say there wasn’t quite the same pressure on society to make the compromises that were necessary. A lot of people were comfortable with the situation that existed, and that is part of the reason why it had lasted so long.

So yes, in the 1990s, there was a difficult situation. My main frustration was the fact that — knowing that political progress was possible — we were, yet not been able to achieve that which I knew to be possible because of various difficulties, some personal, some of a political nature. So it took a long period of time before the chance that had been there in the 1970s recurred, and even then it took a talks process that lasted, with interruptions, from 1991 to 1998, to produce an agreement. And now we’re four years after the agreement, nearly —well, more than four years after the agreement — and we still haven’t actually changed an awful lot, in some respects. So, the talks took an awful long time. The implementation post-agreement is taking a long time, and that is one of the frustrations about this, that it has taken so long to reach the point of having the political breakthrough. But even after that, we are still struggling in terms of the implementation of the agreement. So, the main frustration comes from the slowness. Yet, I suppose when the historians come to look at it, they might actually find that the slow pace has had some benefits too, in enabling people to adjust and to change attitudes. But, from one’s point of view of being directly in conjunction with events, the slowness has been a bit frustrating, too.

Mr. Trimble, you showed tremendous strength of purpose in insisting on the disarmament process at the height of these talks, not backing down. Can you tell us about that?

David Trimble: We’ve had some small progress on that issue, but the actual problem itself has not been resolved. The whole object of the agreement is to produce peace and democracy in Northern Ireland. We’ve got a lot of progress in terms of building democratic institutions and people working together, and yes, we’ve a much lower level of violence, and people have got a qualitative change in how their lives are conducted. But we haven’t got an absence of violence and we haven’t got rid of the private armies. You can’t say that you’ve got a society that’s operating by purely peaceful and democratic means if you still have various private armies, which have political ambitions, continuing every night again to flex their muscles.

Now, that is the problem. That is the problem and until we can get that problem resolved, then we can’t be confident that, for example, with regard to the Irish republican movement, that its movement into politics has been genuine and not tactical. While it’s involved in politics, that’s fine, but while it still retains a private army, then you cannot be sure that its conversion to peace and democracy is genuine and is permanent. If it retains the option of going back to violence, you can’t really regard it as a normal political or power organization. And, the same is true with regard to the other private armies that exist, and the people that operate them and control them, that while they retain the option of resort to violence, then you can’t regard them as peace-loving democrats. And, that problem of the continuation of armed gangs with political objectives remains.

It’s possible that what you’re seeing is part of a process of change, but we want to see the progress demonstrably taking place, and the goal getting closer. That’s part of the frustration, when things have been moving so slowly, over four years after the agreement. Some of the issues that the agreement settled on paper, we haven’t actually got them settled on the streets. That is quite frustrating, and it tends to drain away support from the process.

One aspect of the situation in Northern Ireland that has been well-covered in the United States is the issue of parading and the “siege of Drumcree.” Could you tell us about your role in that, Mr. Trimble, and why this 1995 incident was so significant?

David Trimble: Yes. The business of parading is quite common in Northern Ireland, as indeed it is in the United States as well, and there are certain cultural reasons for that. And, for those of the Unionist community, the main parades and organizations that they would look at would be those which are Orange, that relate back to the Glorious Revolution at the end of the 17th Century, and those have been happening in Ireland from the 18th Century onwards. Yes, they represent a particular communal view, but they are essentially — to people within the Unionist community — they’re more in terms of a festival or a celebration. In the United States, you have the arrangement with regard to popular parades and all the rest of it, that people have the freedom of assembly and the right to process, and you would not allow and you’d not dream of allowing groups by the threat of violence to inhibit the exercise of that right. And indeed, there have been notable incidents in the United States where the authorities have gone to considerable lengths to ensure that even people that you don’t like have the right to process.

It’s in our Constitution.

David Trimble: It’s in your Constitution. It’s always been in our sense of liberty, as well, but in the United Kingdom we do not have a written constitution in the same way. And in a situation where those things which were popularly regarded as rights are actually dependent on ordinary law and custom and practice, then the situation can evolve differently.

What has happened in Northern Ireland is we’ve got efforts being made to ghettoize society, for people to carve out ghettos and say, “This is our territory and nobody else is allowed to come into it.” And, those ghettos which were carved out haven’t remained static. Some places have expanded. And, what then happened with regard to the Drumcree incident is that a traditional parade, which had been following the same route since 1807, became controversial because part of the territory over which the parade was taking place changed color. And what had been an Orange road became a Green road, and then people living adjacent to that road said that they were going to prevent the parade from taking place.

What had been a Protestant area had become Catholic, and that’s the adjacent territory. What you were actually dealing with was with the main road. There was no question of people parading through the streets of a housing district, but actually coming down the main road. The adjacent housing projects alongside the road had changed color, and the people there were saying, “We will stop this.”

You had that clash between one view of liberty, which was one not very dissimilar from the view that you would take in the United States, and those who were trying to carve out areas which they could then dominate and control. Now, the latter development is actually part of a bigger problem that’s happening in Northern Ireland, in that over the years, the Troubles, the areas which have become sort of recognized, “That is a Green area that’s controlled entirely by republican paramilitaries.” “This is an Orange area; it’s controlled by loyalist paramilitaries.” This is a thoroughly bad situation because it diminishes the areas where there is any degree of common freedom, and it diminishes the areas where the normal laws of society apply. Because, although the authorities are supposed to govern everywhere, and the police are supposed to move in areas which are recognized as being dominated by loyalist paramilitaries or republican paramilitaries, then the normal rules don’t apply and that is a thoroughly bad development, and we’ve had those problems.

It’s the same problems that we’re having with the violence that’s taken place in Belfast over the last few weeks. Again, it is what we call interfaces. In other words, on the boundary line between a republican ghetto and a loyalist ghetto, and there is fighting going on, and those boundary lines are not necessarily static. People are trying to expand their territory one way or the other, and it has produced in Belfast in the last few weeks some very serious riots.

It is that general problem. Parades are a symptom, but the parade in itself is not a problem. Where there’s a problem, it is the ghettoization of society that has taken place. We need to find some way of actually arresting that and changing the context in which it operates. The agreement is supposed to do that.

The agreement tries to set out a set of principles and standards that are applicable to all, to move to a rights-based society, and rights-based approach. But we are a long way from implementing all those matters. Yes, we’ve got the European Convention on Human Rights embodied in domestic law, and we have other structures that are there, but in terms of what happens on the street, I’m afraid it’s the older business of one gang fighting against another gang, one paramilitary group fighting another paramilitary group, the UDF fighting the IRA. That is what is happening on the streets, rather than the rights-based civil society that the agreement envisaged applying throughout society as a whole.

Mr. Hume, you mentioned your role as a historian and the vivid sense of history you felt in Strasbourg. How significant do you think your background as a scholar has been in the work you’ve done for Northern Ireland?

John Hume: The subjects that I specialized in eventually, when I got to university, and got my degree in, were French and history, so that I became a very fluent speaker of another people’s language. And, of course, that obviously developed my whole concept of diversity, and of the actual diversity of the world and it made a big — and of course, my history, as well. Obviously, your education does develop your philosophy, and central to my philosophy, of course, is the whole concept of respect for diversity. The realization is that difference is of the essence of humanity. There’s not two people in the whole world who are the same, and when you look at conflict, no matter where it is, what’s it about? It’s about difference, whether it’s religion, race, or nationality, and the answer to difference, as I have kept saying, is to respect, not to fight about it because difference is an accident of birth. Not one of us chose to be born into any particular community. Therefore, when I see a divided community like our own, I would say to people on the other side of that community, if you had been born into the other community, would you be fighting with what is now your old community and vice versa?

In other words, the essence of unity of any community is respect for diversity. When you look at the founding fathers of the United States, what was their philosophy? It’s often forgotten, but I was very aware and it’s written, summarized on the American cent, E pluribus unum, written large on the grave of Abraham Lincoln, “From many we are one.” The essence of our unity is respect for diversity. And of course, when you consider the founding fathers of the United States were driven out of other countries by poverty, by famine, by conflict, by all of those things, and they decided that those things weren’t going to happen in their new land. And that was a philosophy, and of course, when you consider that, the essence of unity is respect for diversity, that’s a philosophy of peace for the world.

I learned all that as a student, but I also think that education is central to the development of any society. Our generation was the first generation to get full education right through to the university level. That’s why I have been saying publicly, in recent months, that one of the things that we should be sending to Afghanistan is education. When you look at that poor country, 85 percent of its women can’t read or write because women are not allowed to go to school, and 65 percent of the community can’t read or write because they don’t go to school. The only wealth that exists in this world, the only wealth that any country has is people. Without people, any country is a jungle. It’s people who create, and therefore, if there is no education, their talents and creativity will not be fully developed.

Education has transformed our society. I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you if it wasn’t for education and before I grew up, our society was full of intelligent people who didn’t get educated, and very many of them were known as street characters, you know, and were very humorous people. I’ve been asked in recent interviews, “Are there any street characters in your city now?” and I say, “No, there’s not.” He says, “Well, where are they?” and I said, “They’re all university professors.” But, that’s the case. Education and I think this is a real strong message, particularly for third world countries and countries that are suffering terrible poverty and underdevelopment. While it’s right and proper to send them food and money, we should also — the best help we can give them is send them education, ensure that all of their young people and children will be fully educated because when that happens, a country will then become self-sufficient because its own people will create its own wealth.

Mr. Trimble, you taught for some years at Queens University School of Law. Do you think that being a law professor has informed what you have accomplished in recent years?

David Trimble: Law and politics go naturally together because so much of political life does revolve around law and legislation. The mental techniques that lawyers develop are particularly helpful, I think, in dealing certainly with legislation, but also, I think, in dealing with politics as well, and that is the ability to analyze, to cope with a considerable volume of material, and to try and pick out from that what is relevant, what is not relevant, are particularly important and attention to detail also comes through, as well. My own preferred approach, in terms of approaching a political situation, will be not in terms of coming from sweeping, broad principles, or from emotional positions, but from a position of having respect for the facts that you’re dealing with, and looking at them closely, examining what is/what is not possible. A less dramatic perhaps form of approach, but yet one that is absolutely essential, doesn’t mean that you don’t have principles that guide you, and goals that you’re working towards, but it does mean that you focus on what is practicable, and what is realizable, and that you have some respect for the medium with which you are working, which is other people and other particular situations, and you don’t assume that you can remold humanity or change situations by dramatic gestures. So, the painstaking, methodical approach of the lawyer is, I think, actually a desirable thing, in life generally and particularly in political life, where people can quite often succumb to ideological views, and to the belief that it is possible easily to produce revolutionary change, when in fact it’s not.

If it simply remains a matter of the UDA (the Ulster Defense Association), pitched against the Irish Republican Army, then the rest of society will be the loser, and John is quite right in that sense. What we need to do is to change the context entirely, and that is to get away from a society that is going to be dominated by competing sectarian ghettos, to a society where everybody is living by the same set of rules.

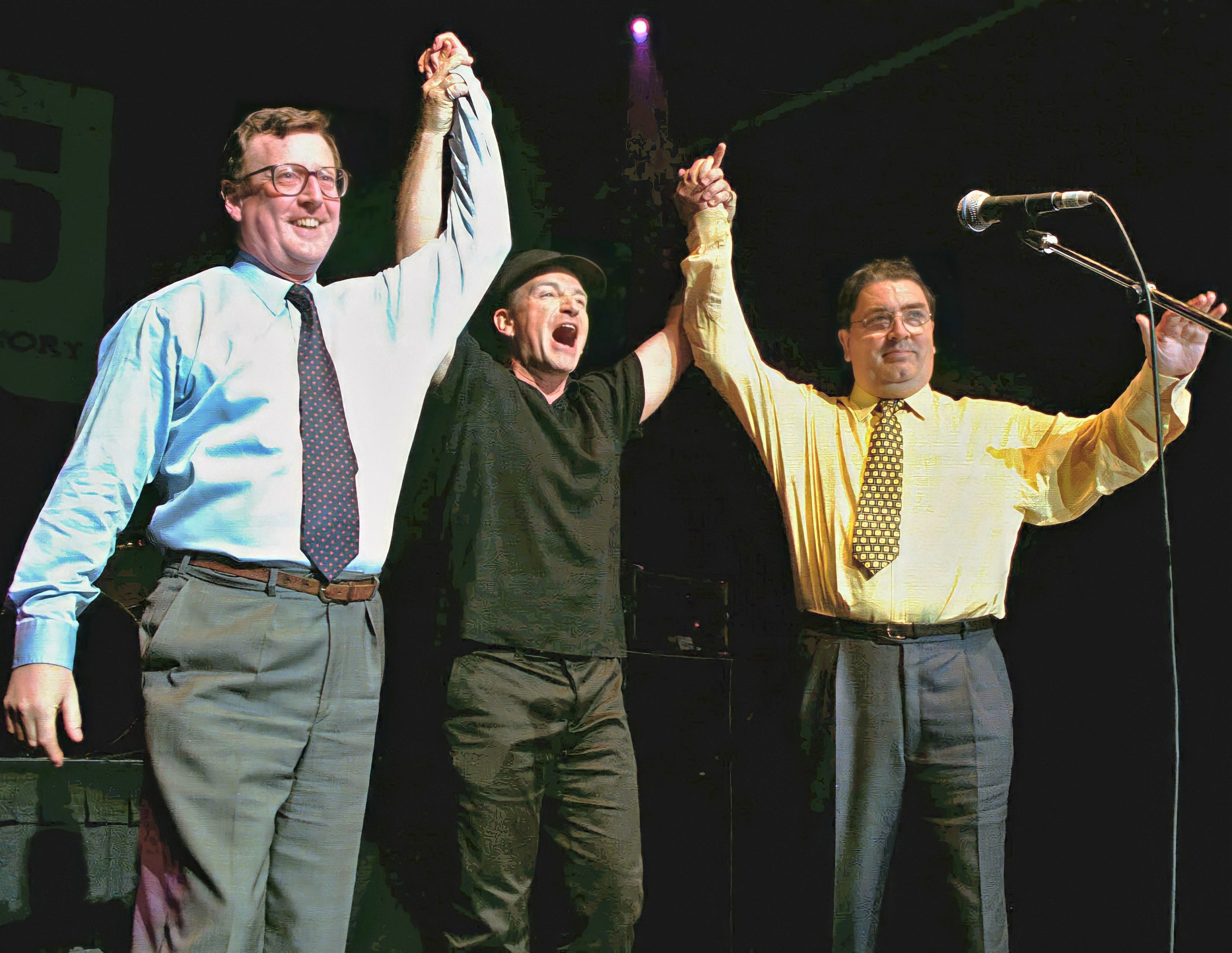

Mr. Hume, talk about what it meant to you and your struggle for peace to get the Nobel Prize.

John Hume: I was, obviously, very honored to receive the Nobel Prize, but as I said when I received it, I saw it not just as an award to myself. I saw it as a very strong statement from one of the most respected organizations in the world, the Nobel Institute, of support for our peace process, and of real sympathy for the people of Northern Ireland. In that sense, since it was awarded to both David Trimble and myself, I believe it strengthened the peace process, because it showed that there was real international sympathy for our people, and support for our peace process.

What did it do for you, Mr. Trimble?

David Trimble: The Nobel Committee did say to us, that they liked to use the Prize constructively, to encourage developments that were taking place. They didn’t sit and wait until you had a situation where everything was settled and there were no more problems. Then making the award was like drawing a line over something that’s finished. They know that they’re acting in an evolving and a changing situation.

I’m glad that they have that tolerance, because what was in my mind, when I first heard about the award, was that in 1977, the Norwegian Nobel Committee had awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to two people from Northern Ireland with regard to their efforts to bring about peace, at a time when there was some hope that those efforts would succeed. But unfortunately, in the fairly short time after the award was made, that hope died, and the award was made to people who were trying hard but that had failed. No reflection on them personally, but nonetheless it did fail.

In the autumn of 1998, we’d got an agreement, and that was quite significant, but I was fully conscious of the difficulties there would be in implementing that agreement, and I knew that the agreement was not guaranteed to succeed. So my first reaction on the award was concern that history should not repeat itself. I didn’t want to see 1997 repeat itself and to find that the award is made, only to find a few months later that the political effort that the award recognizes collapses. That’s why I said at the time, in my first published comment, that I hoped that the award would not prove premature. We’ve managed to keep the process going, and have made progress since then, but mind you, we can’t even say that things are definitively settled and resolved at the moment.

What are the greatest challenges as you look ahead at the future of Northern Ireland?

David Trimble: The problems created by paramilitarism, by the armed gangs that exist, by the danger that those gangs will transmute themselves into Mafia-style organizations. Mafia started in Sicily as a national liberation movement; look how it’s developed since. There is a very serious danger there, and we have a lot of work to do to achieve the objective that we set ourselves in the agreement of producing a society that operates by exclusively peaceful and democratic means.

Mr. Hume, where do you see the big challenges in the future?

John Hume: As we look at our future, our big challenges are, of course, that we are working together in our common interests. Therefore, the big challenge is to make sure that the development of those common interests are successful, which means, largely speaking, real politics, the development of the economy. In other words, making sure that we give hope to our young people, that they can earn a living in the land of their birth because in the land that we have grown up in, many of our young people have had to leave to go to other lands to earn a living. But, the more that we ensure that to happen that will strengthen our community and, of course, it will mean that our young people from the different sections of our community will be working every day under the one roof. They will be spilling their sweat, not their blood and that will break down the real border in Ireland, which is in the minds and hearts of people, and it will break down and erode the prejudices and distrusts of the past, and build a completely new friendship, and a new Ireland will evolve, based on agreement and respect for difference.

Thank you.