How do you account for your lifetime of advocacy and involvement in public life?

Ralph Nader: Well, it’s a thirst for justice. If you know what’s going on and know how society can be improved and happiness advanced, you tend to focus on how to get things done that will help health, safety, opportunity, justice, accountability of powerful institutions to the people they are supposed to serve.

A lot of us experience injustice, feel angry for one reason or another, but you went out and actually did something about it. You knocked on the door of the corporation and the door of government and started yelling. Why did you actually go out there and try to do something about it?

Ralph Nader: I grew up thinking one person can change things. Where did I get that idea? First from my parents, and second from reading American history. So many of the major steps forward in our society’s progress started with just a handful of people. The abolitionist movement against slavery, the women’s right to vote movement started with six women in an upstate New York farm house where they met in 1846. The Civil Rights movement. Environmental rights. Worker rights. The whole labor movement. If you grow up in a mass society and think that nothing can be done unless you have masses of people who all agree all at once to start doing something, then you are not going to count yourself as very significant. You are not going to think that you can begin a thoughtful strategy to change things for the better.

How do you think your parents influenced you?

Ralph Nader: We used to converse at dinner time around the table. Parents and children. We talked about all kinds of issues. From local, neighborhood issues to world issues. It was back and forth, very lively, and very critical. During our early years my mother would relate historical sagas to us for five or ten minutes every lunch hour, when we would come home from school, and it would be continued the next day. I think that built into us a sense that freedom involves responsibility. It isn’t just waving flags and saying, “Look how free we are,” while people’s rights are being trampled sometimes overtly, sometimes beyond their control. Like, pollution for so long wasn’t even viewed as pollution. It was viewed as the price of progress. “Oh, look at all that dirty smoke going out of the factory smoke stack. They must be working.” We got involved in the local community. Little issues at first. We went to the town meeting. Talked about how the town could get a sewage system, instead of dumping the sewage in a local river. Little things that came up in school. We also had a library very near our home. We spent a lot of time in the library. We didn’t have television to distract us, we didn’t have video games to distract us. We had a lot of personal interaction. I can’t imagine myself as a child spending 25 hours a week looking at a machine, called a TV tube.

Was there a particular moment as a kid that was a catalyst for inspiring you in this direction?

Ralph Nader: Not really. It was a very gradual type evolution of thinking. Our parents never lectured us. They gave us proverbs, history, indirection, they set an example for us. They were active in the local community and I think, just by asking us questions. There were things that stand out. One time when I was nine or ten years old, I came home from school, went into the back yard, it was a nice spring day, and my dad said to me “Well Ralph, what did you learn in school today? Did you learn how to believe, or did you learn how to think?” So I’m saying to myself, what’s the difference between the two? I go up to my room, scratching my head. I remembered that not many months earlier, I was in my classroom and the teacher said, “There is a public library here in town, right across the street.” And I raised my hand and I said, “It’s not a public library, it’s a memorial private library that a philanthropist established.” And she was so outraged that I challenged her in front of the other students, she put me in the dunce chair, in effect. You see, she wanted me to believe, not to think.

What kind of a student were you? What were you like in school?

Ralph Nader: Studious. But I liked to play informal sports. I didn’t like to play in formal teams because I had too many things that I wanted to do, and I didn’t have the time just to have a set time everyday I had to go on a baseball team. But we played a lot of sandlot baseball, and football, and hiked a lot. There were a lot of streams, and fishing, and there are a lot of woods. It was a very nice area of the country, where almost everything was within ten or 15 minutes’ walk. You could go to the lakes, the rivers, the streams, the library, the schools, the stores, the city hall, the county courthouse, the firehouse, the hospital, not to mention your friends’ homes, all the doctors, dentists’ offices, the banks, all within ten, 15 minutes’ walk. There is something different growing up in a small town, compared with a huge metropolis, where you look up and you can’t see the sky unless you look straight up, because of the buildings.

You think that growing up in that kind of small town atmosphere contributed to your sense of wanting to preserve something?

Ralph Nader: Yes, definitely. First of all, it was to human scale. It was a town of about 10,000 people. It had at one time over 50 factories; it was a real production town. They produced clocks, and pins, and Waring blenders, and all kinds of things. You could hear the moo of the cows, and the next day you would be drinking their milk. It was very self-contained in that sense, but more important was that you got the sense that you could do something. There was the town meeting form of government and you could go to the town meeting, and the citizens could, in effect, enact laws just by voting in a town meeting or in a referendum. There was all too much apathy among some people, but in terms of a democratic structure, you couldn’t do it much better, because the people composed the town meetings and they could overrule or establish policy in the town. So that gave you a real feeling that if we wanted to get off our duff and really get involved, we could. There were no excuses. You couldn’t say, “Aw, it’s that big company on the top of the hill,” or “that big political machine,” or a city hall, that’s five miles away by subway. It was right down to human scale.

In your early years, were there any teachers or books that influenced you in particular?

Ralph Nader: Yes, very much so. I would be reading the early muckrakers’ books. Ida Tarbell on Standard Oil, or Upton Sinclair on the meat plants in Chicago. And I would be quite young reading these books, ten, eleven, twelve, and trembling with excitement. I remember how exciting it was to read the books. Teachers? There were about five or six teachers who really had an impression on me. One history teacher, one day we were walking into the class and she had right on the blackboard a message. It said, “Gone: One minute, sixty seconds. Don’t bother looking for it, for you will never find it again.” And her point was, don’t waste time because if you waste time, you are never going to recover that time that you wasted. A good lesson.

What excited you so much about the books you read as a kid?

Ralph Nader: Well, I was very interested in books that detailed injustice, and how people who are underdogs were mistreated, throughout history, whether they were peasants, or workers in the industrial plants a hundred years ago. And these books exposed the brutality or injustice or unfairness that powerful political and business and other interests dealt out to workers and some children — child labor. These kids would be working in these industrial plants in England and the United States, sometimes 16 hours a day, six days a week, impairing their health. And the books usually analyzed why these things occurred and what reforms needed to be made. So I was very fascinated by it, just as a person my age, at age 11 or 12, would be reading detective stories, or the stories of explorers and the dangers they were exposed to as they discovered continents. I would be fascinated by the muckrakers, who were called muckrakers by President Theodore Roosevelt, because these were the reporters who would rake the muck and expose a bad situation in government or business.

Eleven- and 12-year-olds can read that stuff and say, “Boy, I’m glad that’s not me.” You had a different response. Why did these events and these people and this writing so move you?

Ralph Nader: That’s what life was all about: the struggle for decency and fairness and opportunity and justice. We were taught that a long time ago that that’s what’s important in life. It doesn’t mean you don’t go out and play ball or ride a bicycle or have fun. It means that the reason why you can sit there in a living room in a nice town is because there were people before you who paid some attention to reducing or eliminating injustice in society and we have the same obligation to do that for our and future generations. We were taught that indirectly by our parents and our friends as small children.

You went on to Princeton, and to Harvard Law, and you clearly could have gone about this in a different way. You could have worked from within the power structure. Why this path?

Ralph Nader: First of all, I didn’t believe in trivializing myself. As long as we are going to spend time and our respective talents, we shouldn’t have a low estimate of our significance and what we can contribute. Too many people who go to the best schools, and get great grades, are confronted with a choice of trivial work that is very high paid, and has some sort of surface status, like senior partner in a law firm, or corporate executive, but most of the work can be done by anybody. If they didn’t do the work, there would be somebody sliding right in to do the same work. And, it’s work where you don’t often take your conscience to work with you every day. You leave your conscience at home, and you apply your talents to clients, or whatever demands the business or profession makes of you. On the other hand, there is an enormous amount of exciting work that needs to be done in this country. It may not pay as much, but it will still give you a decent standard of living, but you take your conscience to work so you apply your value system and your talents. That is real job enrichment. Nothing can compare with that one. I see senior partners at age 65 or 70, who have made millions of dollars in law firms, come up to me and say that they are pretty disappointed in their life and could they do something else in the years that they have post-retirement. You can just see that they look back, and basically they did it all for the money. They didn’t really enjoy that much. They could rationalize it; it was intellectually challenging, and they met important people, but they didn’t really come close to making the contribution they could have made, given their power, leverage, status, and intellect.

What kind of reactions have you heard during your career from your old classmates from Princeton or Harvard, people who clearly went in different directions?

Ralph Nader: They couldn’t understand what I was doing. When I was in Washington in the early 60s, and I was talking to some of my old classmates about auto safety, and I was going to try to get General Motors and other companies to adhere to mandatory safety standards, they thought I was a front for the CIA! (Laughs) They thought it was just a cover story! But they realized later that it was a genuine issue.

They couldn’t believe that their classmate was doing this kind of thing?

Ralph Nader: No, they couldn’t, but now they’re in their mid-50s, they are beginning to want to do the same thing. They’ve raised their children, they have some financial security, and they are looking back saying, “I want to do what I want to do for once.” And I think there are a lot of problems in the country, and I want to try to work on one or more of them.

We actually have set up a center for civic leadership in Princeton, supported by our class (the Princeton class of ’55) precisely because more and more members of the class, as they went into their 50s, began to realize that there were important things they hadn’t been doing. They wanted to make up for it by contributing to this society. Now that they had attained some measure of influence and skill, they wanted to give something back. Organizing alumni classes is a great frontier of expanding the citizen movement in the country. We all knew each other when we were 17 and 18, and when you know each other at that age, you don’t take any malarkey from one another. You can be very candid with on another, and you are not posturing, because you knew each other so many years ago. I think alumni classes are cohesive associations that can do wonderful things as they move into their 35th reunion and on.

How do you choose the issues you become involved in? How do you decide?

Ralph Nader: In two ways. One, you look around the world, and there are plenty of problems. You never have a difficulty in having plenty of problems to choose from. But you say, do we have a capacity to do something about this? If it’s a purely biology problem, we don’t have any biologists, we’ve never done anything in biology. We say we don’t have the capacity to do that. Second is, do we have the resource to make a difference if we enter it? And thirdly, do we want to do just this one episode, or do we want to do it year after year? Do we want to just go after one problem with railroad safety, or do you want to set up a railroad safety group? So we try to make our decisions in all those areas.

The second way we make a decision is made for us. For example, when the Watergate scandal occurred, Nixon fired the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox. We took his case, and won. He was illegally fired. So that was not something we planned, that was thrust upon us. And we always have to be flexible, so if a catastrophe occurs, we are flexible enough to move some of our people or resources into this area.

How do you see yourself? Do you see yourself as part of an American tradition? Do you see yourself as a voice in the wilderness? Do you see yourself as a lawyer in another arena?

Ralph Nader: Part of American tradition. A combination of the muckraking tradition and challenging corporate abuse and government abdication and not just writing about it, but actually having the ability with our associates and colleague groups to lobby, to litigate, to get it done. In that sense, we are pioneering new ground. We are trying to establish the role of a full-time citizen, people who have causes to change the country for the better, and who do it full-time, everyday. For this, we have to get the funding from foundations, philanthropists, people who provide bequests, cold mailings to people to contribute 20 dollars when they get the appeal in the mail. All of these are ways to get the job furthered, but I think there is an opportunity for hundreds of thousands of full-time citizens in this country, working on city hall, on the marketplace, trying to anticipate problems so they don’t have a crisis on their hands. We could have anticipated the lead contamination problem with millions of children, for example. We could have anticipated in this nation the asbestos contamination disaster, which is leading to hundreds of thousands of injuries and deaths. A lot of things we could have anticipated, if people went to work everyday as full-time citizens, not just working for other organizations to make a profit or to provide a social service, important as they are. There is a very important job to be done generating justice, producing justice in the country.

Of all the things you’ve been involved in, of all the things you’ve done, what are you the proudest of?

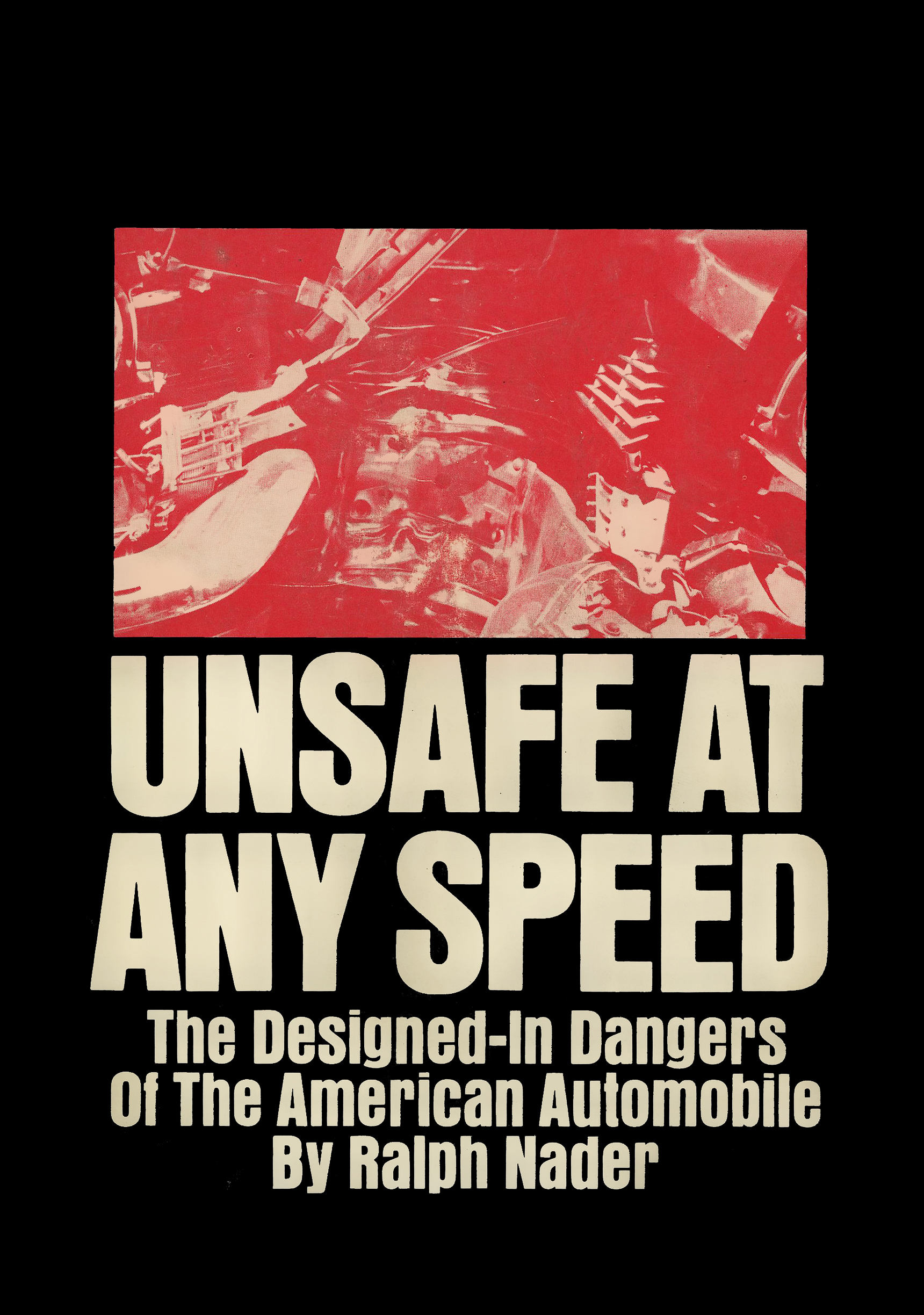

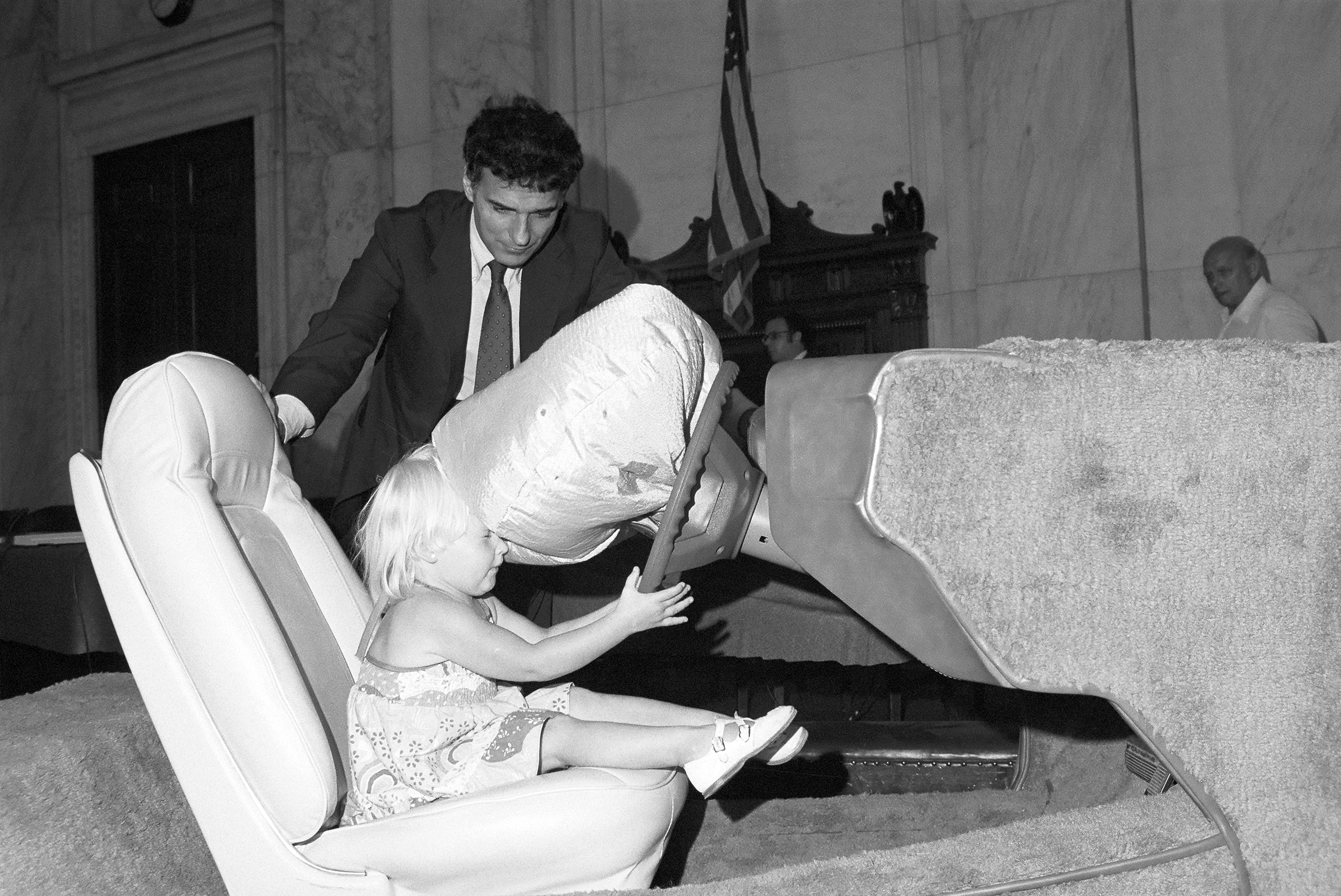

Ralph Nader: I think three things. One is the great advances in auto safety. I mean, there are tens of thousands of people being saved every year because cars are safer, and millions of people over a decade, injuries prevented. I think that’s a good example of the need to make technology more humane. We may benefit from a lot of technologies, but they exact a cost. Emphysema, cancer, soil contamination, contaminated water, death and injury on the highway. We’ve got to put more effort on making them more humane. The second contribution is, Freedom of Information Act. Information is the currency of democracy. If people don’t have information about business or government, they can’t get to first base in trying to use their mind and their value system to make business and government behave better. We have the best freedom of information law in this country, and it’s up to citizens to use it and enforce it. The government is not an enforcer of the Freedom of Information Act, unlike most laws.

The third contribution is establishing a model for citizen action around the country. Establishing a motivation for people to say, “We can do it, too. They’ve done it, we’ve seen how they’ve done it, we’ve got their citizen action manuals and we can do it too. We can fight city hall. You can fight Exxon. We can get change for the better in the country.” And these are people who often we’ll never know, and we will never hear about, but they could be in Arkansas, or they can be in Montana or Florida, and they’ve taken heart from what we’ve done. And, they’ve felt that it can be done. There’s a lot of intimidation. People are often fearful of standing tall, speaking up against local politicians, or businesses or powerful interests. I think that in that sense, that’s probably our most enduring legacy. There’s also in addition to the ripple effect, there’s a deterrent effect. I’ve had people in business tell me this that what they used to get away with years ago they would never try now because they know there are citizen groups out there, environment, consumer, neighborhood groups who are going to watch them, blow the whistle on them. Make sure that they’ll pay a penalty for being out of line and harming innocent people.

How would you define citizenship? What is a good citizen in America?

Ralph Nader: A good citizen is not just a person who votes all the time. A good citizen works between elections to take on an injustice, or participate in a local, state, or national institutions. Whether it’s the schools, or the town meetings, or whether it’s a national citizen group to reform government or improve the campaign finance mess — there are roles for citizens. It involves time and talent, determination, resiliency, the ability to communicate and to say to one and all: The Constitution is not just a parchment to be saluted on the Fourth of July. It’s a document that gives you living rights and responsibilities which we should take hold of. Because democracy is like a coral reef; it’s built up little by little by little. You look at it, and it looks so beautiful, but the reverse is true, too. It deteriorates little by little. When you don’t stand up to someone who is abridging your rights, when you don’t report someone who is violating the norms or the laws of the community — and I’m not just talking about burglaries or vandalism, I’m talking about someone who basically coerces people against their Constitutional rights — if you don’t do that, next time, more of these misbehaving people are going to say, “We can get away with it. We got away with it last month, we can move even deeper into eroding people’s rights.” So it’s important for young people to grow up learning their rights because if you don’t know your rights, how are you going to use your rights? As my parents said, “If you don’t use your rights, you are eventually going to lose your rights.”

Who else has been important in your life? Do you have any heroes or role models, in addition to your parents and family?

Ralph Nader: Some good professors in college. An anthropology professor and a political science professor who really were very stimulating, opened up a lot of windows for me and my classmates. But I think there are historical people: Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln, George Mason. These were people who I found very wise. And in college, the man I was really most impressed with in the 20th century was Alfred North Whitehead, the British mathematician and philosopher. Not to mention Lincoln Steffens and the muckrakers, which were my cup of tea.

What are the frustrations? What have been your disappointments?

Ralph Nader: A lot of disappointments. But you don’t want them to gain a further victory by weakening your will to persist and to respond and to become even a more skilled citizen. Disappointments: we should have had airbags in cars 18 years ago. Just think of all the Americans who’d be alive today, or all the people who would not be in wheelchairs, all the anguish prevented, not to mention the economic costs. It took us 20 years to get the airbags now coming in cars as standard equipment. By the mid-90s they should be as expected as apple pie.

I wasn’t prepared for such a deterioration in both the congressional and executive branches of government. Things are a lot worse now in Washington than they were ten, twenty, thirty years ago. The giveaways of the people’s assets — the federal lands, the minerals, the R&D that the taxpayers paid for — is bigger than ever. Corruption is bigger. Money in campaigns is more influential in what Congress does or doesn’t do. And I’ve seen more and more that the federal government can really be lawless with impunity. The president can refuse to spend funds that he’s supposed to spend by congressional authority. They can engage in foreign adventures, they can violate people’s civil liberties, they can refuse to enforce safety laws, and nothing happens. Because the way the laws are written, they authorize the government to do the right thing, but they don’t give people in the country the power to make them do the right thing under the law. If you file suit, the judges have a doctrine that says, “No standing to sue.” “Who are you, taxpayer or citizen? You can’t challenge the government,” and the doors close. It often takes money to challenge the government.

So I am seeing more and more institutionalized lawlessness, where about the only bounds on government behavior is public relations. The more they think they can fool the people and get away with it, even those boundaries are limited. And, if the press is concentrated in a few media conglomerates, and there is not much diversity and they have a cushy relationship with their government officials because the government officials will give them stories from time to time, then another boundary against government lawlessness deteriorates. We have got a great future if we wake up to it in this country. And, anybody who starts out in this country who thinks that they can’t be a leader ought to think again. There has never been a greater demand for leadership, in all areas: media, education, churches, government, business, you name it. There is no long waiting list to be a leader in this country.

What does it take to be a leader, to do what you’ve done and are still doing?

Ralph Nader: Well, I think the first step is a certain personal equanimity. You have to be at peace with yourself. You can’t have a lot of internal demons and anxieties and psychoses and hang-ups and addictions, and be overly concerned with what people think of you if you have different kinds of opinions. So obviously, if your personal life is not in order, you are not going to have a very vigorous civic life. You are going to be very introverted, you are going to be worried sick over brown spots on your hands if you are middle aged, or if you are a teenager, over whether your nose is shaped just right, or you are pretty enough for your friends to associate with you. And if you are addicted to alcohol or drugs, you are not going to be an effective citizen.

The beauty of citizen involvement is that when your horizon expands and you think more of your own personal significance, then all your little personal hang-ups, which loomed so large in your daily life, suddenly begin to recede and fall and melt away. And you look back and you say, “How could I have ever been bothered by whether my appearance was just right according to the latest Vogue magazine, or the Revlon ad?” That’s why it’s so important to look at citizen action as a form of human happiness. It is a form of human happiness. It is a discovery of human happiness to go into this society of ours and grapple with problems and come out looking back and saying, “Well, the life of a lot of people is better because of what I did.” If people will look at citizen action as a source of joy, I think they are more likely to go into it. There are tremendous rewards. You can’t put a dollar figure on them, but you can put a permanent impression on them. You’ll find they are the most enjoyable times of your life.

If there was one problem you could solve in this country, what would it be?

Ralph Nader: How to get more people involved in making a democracy work. The theory of democracy is that the more people that are knowledgeable about what’s going on, and are involved, the more likely the better ideas are going to come to the forefront. But if just a few people dominate many in various areas, whether it’s in a city, or in a nation, or in one direction or another tax policy or foreign policy, they may make mistakes because they don’t have all the wisdom in their heads. This whole idea of a marketplace of ideas is also a marketplace of engagement and involvement. Once we can develop opportunities and institutions for people of all ages and all backgrounds to get involved in the civic challenges of their choice, then a lot these more ‘headline problems’ are going to be addressed, whether they’re government deficits, or inadequate housing, poverty, discrimination, or what have you. That’s what we are working on: to make it easier and easier for people to go into the democratic flow of things, with a sense of confidence that they can improve that school, they can reduce street crime, they can make Uncle Sam behave, they can tame the corporate tiger.

Looking back on it, do you have any regrets? Were there mistakes that you wish you could have another crack at, or things you’d do differently?

Ralph Nader: Oh, a lot of mistakes. The biggest one is that I would have done differently, I would have almost immediately, in the late 60s, tried to work with educators to get citizen training courses in elementary schools and high schools. So instead of studying a dry civics book, we’d get the children involved in problems in their own community, or in their neighborhood — that also connect to their books, their classes and their libraries and their laboratories. So for example, they say, “I wonder how clean the local water system is for drinking?” and they learn how to do the test for cadmium and lead in their chemistry lab, and they connect with the purification department in the community, learn about the water purification technology, what is available that isn’t being used. They put out a report, have a news conference. You see, they’ve learned chemistry, learned a little bit about human health, about bureaucracy, about how to get the issue across. That is the biggest mistake we made that we didn’t make a major effort in that area because think of the thousands of youngsters who would have come out with that pleasure in their background of having made a difference at age ten or twelve, or fifteen. Now they could be the leaders in the country. We are recovering from that lapse and we are now working on a civic curriculum for the schools.

What do you say to a young man or woman who comes to you and seeks advice, who might want to follow in your footsteps?

Ralph Nader: I’d ask them what’s their passion in terms of justice. They usually have one or two areas that really affect their sense of their mission, what they are all about. If there is an opportunity in our groups, fine. But if we don’t work on this problem, there are catalogues of citizens’ groups. We have a book called Good Works that now has 850 citizens’ groups who would love to have young people consider being part of them. We did a report years ago with high school graduates, just out of high school, on nursing home abuses. They worked in nursing homes, they came to Washington, they researched, they wrote a book, and then they went on radio and TV, testified before Congress. And all this concern led to one of our associates starting the National Coalition for Nursing Home Reform, and she’s still at it, with chapters all over the country.

Let me ask it a different way. Is that something that you can prepare for?

Ralph Nader: Yes. Citizenship requires skills like any other occupation or profession, and it’s good to learn on the job. You can read about citizen movements, the farmer, Populist, Progressive movements at the turn of the century, and the Civil Rights movement. But it’s good to learn it by doing. And, you get better every year you get better. You know how to develop strategies and coalitions and how to get the attention of the media and how to use the levers of action, and how to be perfectly willing to generate controversy which gets people thinking.

Do you have room in your life for anything else?

Ralph Nader: I go to a few movies a year. I watch championship sports. I like to watch the World Series and the finals of the NBA. I watch some symphonies on TV and some plays. But I enjoy my work so much that I have to be pulled away from my work into leisure.

What are you looking forward to at this point in your career? What more do you want to achieve?

Ralph Nader: Ways to start more citizen organizations for all age groups. I’d like to start a children’s citizens’ organization, modeled after chapters for Boy Scouts, where children learn how to be effective citizens at their own pace, with the help of their teachers and people in the community.

The schools and the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts and the home and the family were all supposed to be taking care of these things. Where have we gone wrong?

Ralph Nader: First of all, children today spend less time with adults, including their parents, than any generation in American history. They are spending more and more of their time in front of television screens, video screens, and with their peer group, which often is a merchandising outlet for all the things that are huckstered to the children. Secondly, that many institutions in our country which we look at benignly as doing good, are avoiding controversy. When you avoid controversy, you are avoiding some pretty bad injustices and you become bland. You become goody two-shoes types. And it’s important for the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts, for example, to go right into local pollution problems in their communities. Even if they offend some company whose executives may be associated with the Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts. We really have to focus on this. The avoidance of confronting unjust power, the avoidance of controversy, has gotten into our language. There are people who sit around the table of some influence in the community, and they’ve got languages of avoidance, bureaucratic slogans, instead of saying, “Look, some people are going to have to back off, some people are going to have to give up some of their power, some of their wealth, some of their influence, if we are going to have a more just resolution of problems for the rest of the people in this community or society.”

And there is a way to do it inside the system.

Ralph Nader: There is a lot of elbow room within the Constitutional system, but as the years pass and things get worse, the laws become themselves an instrument of injustice, because they are under the control of the abusers of power. We mustn’t ever allow our country to fall into that low state of affairs.

I am also hearing you saying, don’t be afraid. Don’t be afraid of controversy. Don’t be afraid to follow your own conscience or convictions. How important is that?

Ralph Nader: It’s important to be able to stand tall, have the courage of your convictions and to have resilience if you are up against a disappointment or a temporary defeat. In fact, some of the same features on the athletic arena, basketball court, baseball field, football field, where you never give up, you keep bouncing back and you hold you head high when you walk off the field those are the kinds of characteristics young people should have in a much more important field called the citizen arena because that’s what’s going to affect the quality of their job, their standard of living, what their children are going to grow up in, and what’s called the pursuit of happiness.

How do you stand up to critics? To people who attack you for what you are doing?

Ralph Nader: You can’t have a thin skin. You’ve got to realize that you are going to have to take what you give out. Sometimes you are going to take a lot of unfair criticism, criticism designed to destabilize the credibility you have on a certain issue, but there is a certain robust pleasure in that. If you have the right attitude, you won’t be so demoralized. You will expect it, you will know how to respond to it, you will know how to benefit from it if it’s legitimate. You will know how to reject it if it isn’t legitimate.

If you could talk to somebody you haven’t met, dead or alive, who is it that you would like to sit across from and ask questions of? Is there somebody you would really like to have a conversation with?

Ralph Nader: Jesus Christ, who had a very strategic sense of getting people to accept his beliefs. And Voltaire, whose wit and insight were quite contributory toward a detached view of society, which is important; you can get so immersed that you lose your perspective. Confucius, who condensed a lot of wisdom into a very few words, something our politicians could benefit from these days. And Abraham Lincoln. Franklin D. Roosevelt, see how he responded in both economic crisis and war time crises. The great educators. John Dewey might want to know about what happened to some of his followers and doctrines, and schools. Especially in the athletic area, Lou Gehrig, who is my hero because he symbolized stamina under all conditions of pain and success by playing 2130 baseball games consecutively. I never lost the lesson of his performance, how important it was to overcome, be resilient, and to stay with it, stay the course.

Did you read Frank Graham’s biography of Lou Gehrig?

Ralph Nader: Oh, yeah. There is a new one that has just come out, just about four months ago.

This was just wonderful. Thank you for your time.