Be sensitive. Insensitivity brings indifference and nothing is worse than indifference. Indifference makes that person dead before the person dies. Indifference means there is a kind of apathy that sets in and you no longer appreciate beauty, friendship, goodness, or anything.

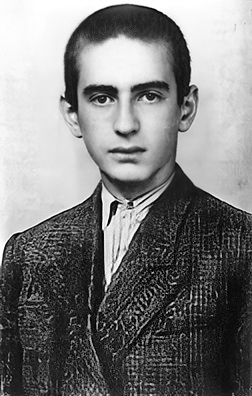

Elie Wiesel was born in the small town of Sighet in Transylvania, where people of different languages and religions have lived side by side for centuries, sometimes peacefully, sometimes in bitter conflict. The region was long claimed by both Hungary and Romania. In the 20th century, it changed hands repeatedly, a hostage to the fortunes of war.

Elie Wiesel grew up in the close-knit Jewish community of Sighet. While the family spoke Yiddish at home, they read newspapers and conducted their grocery business in German, Hungarian or Romanian as the occasion demanded. Ukrainian, Russian and other languages were also widely spoken in the town. Elie began religious studies in classical Hebrew almost as soon as he could speak. The young boy’s life centered entirely on his religious studies. He loved the mystical tradition and folk tales of the Hassidic sect of Judaism, to which his mother’s family belonged. His father, though religious, encouraged the boy to study the modern Hebrew language and concentrate on his secular studies. The first years of World War II left Sighet relatively untouched. Although the village changed hands from Romania to Hungary, the Wiesel family believed they were safe from the persecutions suffered by Jews in Germany and Poland.

The secure world of Wiesel’s childhood ended abruptly with the arrival of the Nazis in Sighet in 1944. The Jewish inhabitants of the village were deported en masse to concentration camps in Poland. The 15-year-old boy was separated from his mother and sister immediately on arrival in Auschwitz. He never saw them again. He managed to remain with his father for the next year as they were worked almost to death, starved, beaten, and shuttled from camp to camp on foot, or in open cattle cars, in driving snow, without food, proper shoes, or clothing. In the last months of the war, Wiesel’s father succumbed to dysentery, starvation, exhaustion and exposure.

After the war, the teenaged Wiesel found asylum in France, where he learned for the first time that his two older sisters had survived the war. Wiesel mastered the French language and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, while supporting himself as a choir master and teacher of Hebrew. He became a professional journalist, writing for newspapers in both France and Israel.

For ten years, he observed a self-imposed vow of silence and wrote nothing about his wartime experience. In 1955, at the urging of the Catholic writer Francois Mauriac, he set down his memories in Yiddish, in a 900-page work entitled Un die welt hot geshvign (And the world kept silent). The book was first published in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Wiesel compressed the work into a 127-page French adaptation, La Nuit (Night), but several years passed before he was able to find a publisher for the French or English versions of the work. Even after Wiesel found publishers for the French and English translations, the book sold few copies.

In 1956, while he was in New York reporting on the United Nations, Elie Wiesel was struck by a taxi cab. His injuries confined him to a wheelchair for almost a year. Unable to renew the French document which had allowed him to travel as a “stateless” person, Wiesel applied successfully for American citizenship. Once he recovered, he remained in New York and became a feature writer for the Yiddish-language newspaper, The Jewish Daily Forward (Der forverts). Wiesel continued to write books in French, including the semi-autobiographical novels L’Aube (Dawn), and Le Jour (translated as The Accident). In his novel La Ville de la Chance (translated as The Town Beyond the Wall ), Wiesel imagined a return to his home town, a journey he did not undertake in life until after the book was published.

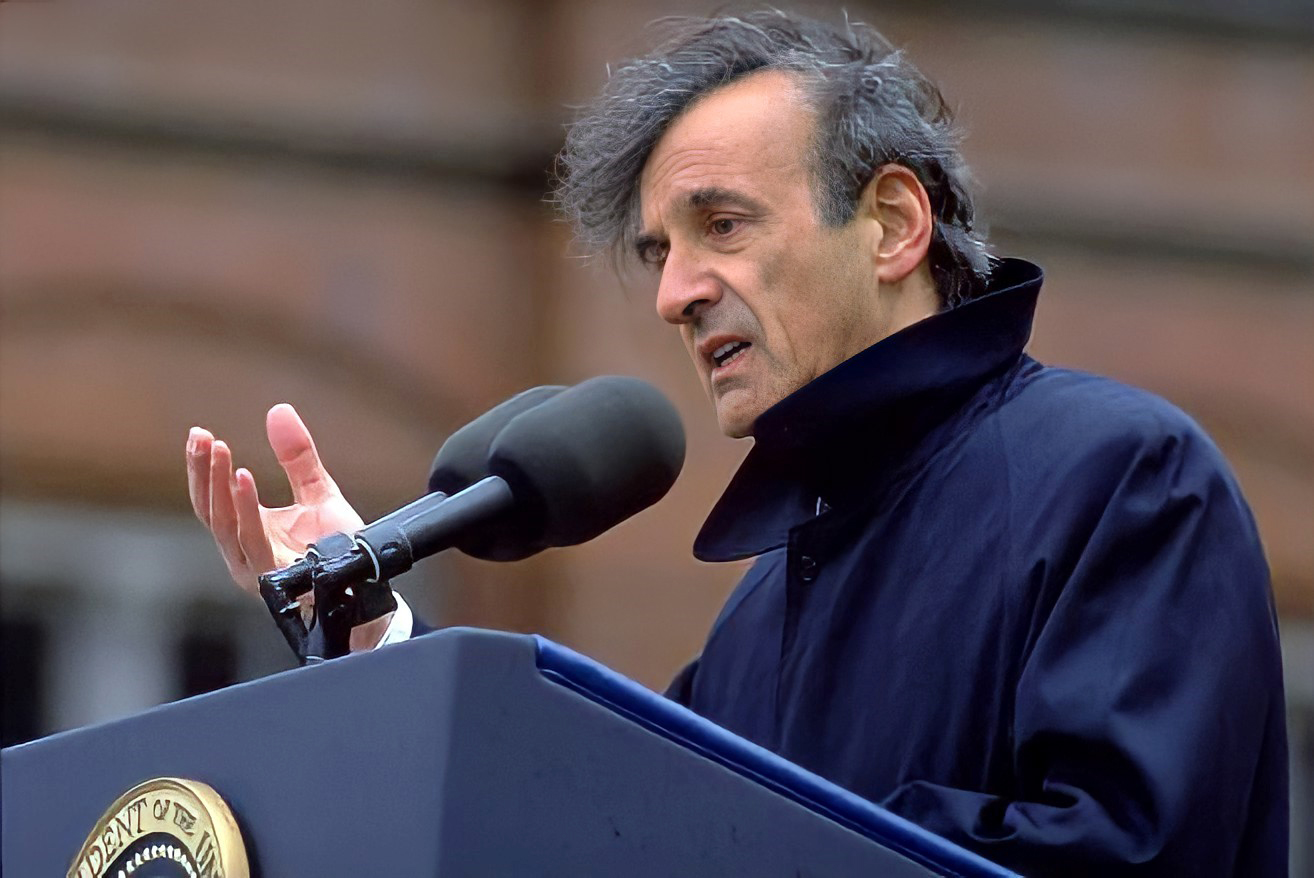

As these and other books brought Wiesel to the attention of readers and critics, translations of Night found an audience at last, and Wiesel became an unofficial spokesman for the survivors of the Holocaust. At the same time, he took an increasing interest in the plight of persecuted Jews in the Soviet Union. He first traveled to the USSR in 1965 and reported on his travels in The Jews of Silence. His 1968 account of the Six-Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbors appeared in English as A Beggar in Jerusalem. In time, Wiesel was able to use his fame to plead for justice for oppressed peoples in the Soviet Union, South Africa, Vietnam, Biafra and Bangladesh. In 1976, Elie Wiesel was named Andrew Mellon Professor of Humanities at Boston University. He also taught at the City University of New York and was a visiting scholar at Yale University. In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed Elie Wiesel Chairman of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council. Wiesel was a driving force behind the establishment of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. His words, “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness,” are engraved in stone at the entrance to the museum. In 1985 he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, and in 1986, the Nobel Prize for Peace. “Wise men remember best,” Mr. Wiesel said in his Nobel lecture. “And yet, it is surely human to forget, even to want to forget…Only God and God alone can and must remember everything.” In 1992, President George H.W. Bush presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award of the United States.

In the midst of his activities as a human rights activist, Wiesel continued his career as a literary artist. He wrote plays including Zalmen or the Madness of God and The Trial of God (Le Proces de Shamgorod). His other novels include The Gates of the Forest, The Oath, The Testament, and The Fifth Son. His essays and short stories have been collected in the volumes Legends of Our Time, One Generation After, and A Jew Today. The English translation of his memoirs was published in 1995 as All Rivers Run to the Sea. A second volume of memoirs, And the Sea Is Never Full, appeared in 2000.

As his international fame grew, Wiesel spoke out on behalf of the victims of genocide and oppression all over the world, from Bosnia to Darfur. Although he became known to millions for his human rights activism, he by no means abandoned the art of fiction. His later novels included A Mad Desire to Dance (2009) and The Sonderberg Case (2010), a tale set in contemporary New York City, with a cast of characters including Holocaust survivors, Germans, American emigrants to Israel and New York literati. Elie Wiesel and his wife, Marion, made their home in New York City. His wife, the former Marion Erster Rose, was a Holocaust survivor; they married in 1969. Since Wiesel wrote his books in French, Marion Wiesel often collaborated with him on their English translations. He died at home in Manhattan, at the age of 87.

Elie Wiesel was only 15 when German troops deported him and his family from their home in Romania to the Auschwitz concentration camp. His father, mother, and younger sister all died at the hands of the Nazis.

The young boy survived forced labor, forced marches, starvation, disease, beatings and torture to become a world-renowned writer, teacher and spokesman for the oppressed peoples of the earth. He is best known as the most eloquent witness to the great catastrophe to which he was the first to give the name “Holocaust.”

After the war, Elie Wiesel determined to relate his story to the world. His book Night is one of the classic accounts of the Holocaust. Following its publication, Elie Wiesel wrote more than 55 books, including novels, plays, books of essays, biblical commentary and works on Jewish folklore and mysticism. Throughout his career, he continued to speak out for victims of oppression all the world over.

It’s hard for any of us to imagine what you experienced, as an adolescent, in the concentration camps. How did that affect and change what you did with your life?

Elie Wiesel: It affected me a lot. I cannot talk about myself. I like to talk about other people, not about myself, but I’ll try to answer you.

Of course, it had an overwhelming effect. After the war — I was 15 when I entered the camp, I was 16 when I left it, and all of a sudden you become an orphan and you have no one. I had a little sister and I knew, with my mother the first night, that they were swept away by fire. My older sisters I discovered by accident after the war in Paris, where I was in an orphanage. But to be an orphan — you can become an orphan at 50, you are still an orphan. Very often I think of my father and my mother. At any important moment in my life, they are there, thinking, “What an injustice.” To date, I haven’t written much about that period. Of my 40 books, maybe four or five deal with that period because I know that there are no words for it, so all I can try to do is to communicate the incommunicability of the event. Furthermore, I know that even if I found the words, you wouldn’t understand. It is not because I cannot explain that you won’t understand, it is because you won’t understand that I can’t explain.

The idea of the writer’s mission, to be a witness, to be a messenger, was that part of your intention as a writer?

Elie Wiesel: I wasn’t that ambitious really. I wanted to write. I wrote my first book in Yiddish. In 1956, it came out in Buenos Aires, and then in French in 1958, and in New York in 1960.

I wrote it, not for myself really. I wrote it for the other survivors who found it difficult to speak. And I wanted really to tell them, “Look, you must speak. As poorly as we can express our feelings, our memories, but we must try. We are not guaranteeing success, but we must guarantee effort.” I wrote it for them, because the survivors are a kind of most endangered species. Every day, every day there are funerals. And I felt that there for a while they were so neglected, so abandoned, almost humiliated by society after the war. When I became Chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust in 1978, I wanted really to glorify the survivors. There wasn’t a committee that I didn’t appoint a survivor, because I felt they deserve it. The same reason I wrote is really for that mission. It’s always afterwards that, in a way, your friends or your readers convince you that you went beyond that, that you are a messenger, and so forth. I didn’t use those words, I used the words simply, “Look, we have to tell the story as best as we can. And we know that we won’t succeed.” I know I won’t succeed. I know I haven’t succeeded.

Take the word “holocaust.” I am among the first — if not the first — to use it in that context. By accident. I was working on an essay, a biblical commentary, and I wrote about the sacrifice, the binding of Isaac, by his father Abraham. In the Bible, there is a word in Hebrew, ola, which means burned offering. I felt that’s good. That’s “holocaust.” That’s good because it’s fire and father and son. Meaning the son who almost died, but in our case it was the father who died, not the son. The word had so many implications that I felt it was good. Then it became accepted, and everybody used it and then I stopped using it because it was abused. Everything was a holocaust all of a sudden. I heard myself on television once, a sportscaster on television speaking of the defeat of a sports team and he said, “Was that a holocaust!” My God! Everything became a holocaust. In Bosnia, I remember, they spoke about a holocaust. I went to Bosnia to see. I felt, if it is, I must move heaven and earth. Even if it isn’t, I must move heaven and earth to prevent it, but at least not to use the word. Well, all of this really is not very easy, but why should it be?

After the war, you did not speak — you were not a witness — for ten years.

Elie Wiesel: I was. You know…

You can be a silent witness, which means silence itself can become a way of communication. There is so much in silence. There is an archeology of silence. There is a geography of silence. There is a theology of silence. There is a history of silence. Silence is universal and you can work within it, within its own parameters and its own context, and make that silence into a testimony. Job was silent after he lost his children and everything, his fortune and his health. Job, for seven days and seven nights he was silent, and his three friends who came to visit him were also silent. That must have been a powerful silence, a brilliant silence. You see, silence itself can be testimony and I was waiting for ten years, really, but it wasn’t the intention. My intention simply was to be sure that the words I would use are the proper words. I was afraid of language.

What persuaded you to break that silence?

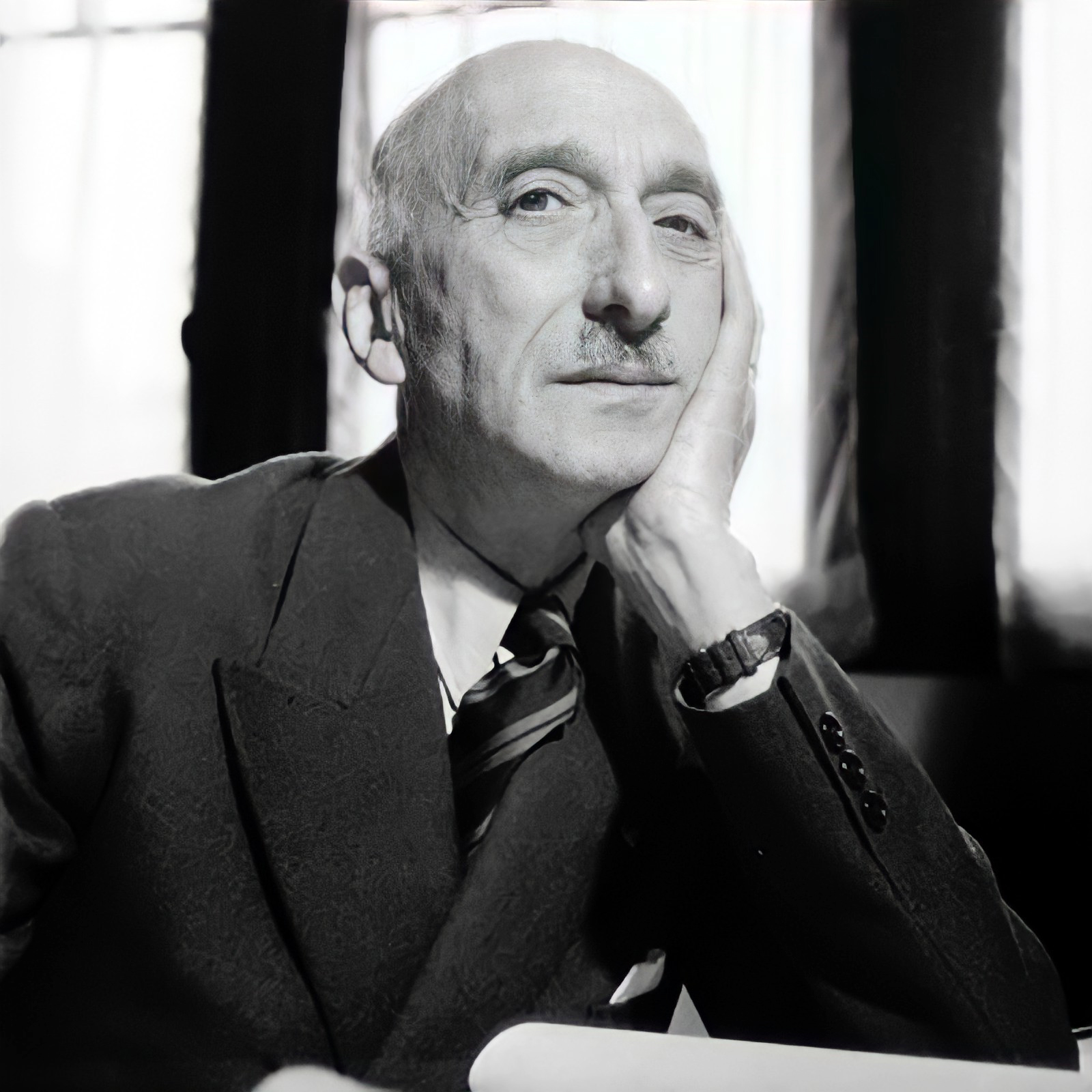

Elie Wiesel: Oh, I knew ten years later I would do something. I had to tell the story. I was a young journalist in Paris. I wanted to meet the Prime Minister of France for my paper. He was, then, a Jew called Mendès-France. But he didn’t offer to see me. I had heard that the French author François Mauriac — a very great Catholic writer and Nobel Prize winner, a member of the Academy — was his guru. Mauriac was his teacher. So I would go to Mauriac, the writer, and I would ask him to introduce me to Mendès-France.

When I came to Mauriac, he accepted to see me. The problem was that he was in love with Jesus. He was the most decent person I ever met in that field — as a writer, as a Catholic writer. Honest, sense of integrity, and he was in love with Jesus. He spoke only of Jesus. Whatever I would ask — Jesus. Finally, I said, “What about Mendès-France?” He said that Mendès-France, like Jesus, was suffering. That’s not what I wanted to hear. I wanted, at one point, to speak about Mendès-France, and I would say to Mauriac, can you introduce me? When he said Jesus again I couldn’t take it, and for the only time in my life I was discourteous, which I regret to this day. I said, “Mr. Mauriac” — we called him Maître — “ten years or so ago, I have seen children, hundreds of Jewish children, who suffered more than Jesus did on his cross and we do not speak about it.” I felt all of a sudden so embarrassed. I closed my notebook and went to the elevator. He ran after me. He pulled me back; he sat down in his chair, and I in mine, and he began weeping. I have rarely seen an old man weep like that, and I felt like such an idiot. I felt like a criminal. This man didn’t deserve that. He was really a pure man, a member of the Resistance. I didn’t know what to do. We stayed there like that, he weeping and I closed in my own remorse. And then, at the end, without saying anything, he simply said, “You know, maybe you should talk about it.” He took me to the elevator and embraced me. And that year, the tenth year, I began writing my narrative. After it was translated from Yiddish into French, I sent it to him. We were very, very close friends until his death. That made me not publish, but write.