What was it like for you as a black kid growing up in the Mississippi Delta in the 1920s and ’30s?

B.B. King: This is going to probably sound funny to you, but I didn’t think I was any different from anyone else, other than I was a black kid instead of being a white kid, and it was a segregated society. We walked to school. The white kids had a school bus. And, I was crazy about Roy Rogers. I liked William Elliott. We called him Wild Bill, never did think of them as being white. They were cowboys, my heroes. I think, trying to answer your question, I had never experienced the North. I didn’t know anything about the North. I didn’t know anything about any other society other than what we lived in. So, the answer to your question? Truthfully? All right with me. It’s just that some people had and some had not, and I wished I could have been one of those that had, now that’s the truth.

What did you do as a kid?

B.B. King: I guess I was the average Afro-American boy or American boy really. I used to hunt, fish, played. I’d shoot marbles. I was never good at any of it. The school I went to, we didn’t have a football team or a basketball team. We played something called base something. It was similar to football, with tackling and all that but you didn’t carry a ball. In other words, whoever could catch you and touch you would put you “in prison,” as we called it, and it was sort of a funny game when I think about it now.

You make it sound as if you had a pretty easy life when you were growing up, but the fact is you didn’t. It was hard for you.

B.B. King: You never miss what you’ve never had. I never had any other life. I didn’t know any other life. I knew that if I went to town on a Saturday, which I did, and there was two fountains, one said “Black” and one said “White.” I didn’t think other than that if you want to stay out of trouble, leave the white one alone. I also noticed that when I went to the rest rooms there was one that said “White Men,” “White Ladies” and “Colored.” That’s all I knew. I grew up with it. It wasn’t like somebody just threw me down there and said, “You don’t bother that…” But I was taught that in my early life. My family would always say — because there was people being lynched around me. I haven’t seen people be lynched, but I’ve seen them after they was. And I was told by some of the elders that, you know, “Unless you do certain things this can happen to you or that can happen to you. You don’t bother the white ladies, you don’t do this, you don’t do that,” and I learned that at an early age and to me it was just part of my training. I think this is why black people never did resist for such a long, long time because if there’s any such thing as being brainwashed I was brainwashed, but it didn’t bother me.

I remember once that a lady was kidnapped and finally she helped the people rob a bank. She had been brainwashed. I was the same, and I didn’t know the difference until people started to tell me. I’d start to hear about the North, past what they call the Mason-Dixon Line. There you can do this or you can do that, just as a person.

We heard about New York. We heard about Los Angeles. We heard about some, but Chicago seemed to be the place you could go and get you a nice car. You could live anywhere you want. You can marry anybody you want. You could date anybody. I started to think about it a little. I’d see people then that had lived up there and had come down and they would be dressed nicely and I still had on my overalls. See overalls was a thing of wear that we had and you wore them every day. Every day you had overalls on. Overalls is jeans with a bib, to me. Well I’d wear them all the week. On Friday night wash them, and dry them and iron them on Saturday morning, and wear them to church on a Sunday. That’s why today I say to myself, “I love to see the young people wear comfortable things.” I have some jeans at the house that I wear them at the house, but I swore if God let me live there is two or three things I would never do again – wear overalls! I would always have me enough to eat if I needed it, and food that I liked to eat. Those three things I swore to myself. If God let me get to be grown, these three things I’m going to have.

What was hardest for you growing up?

B.B. King: Getting up in the morning and going to the fields. I never did like that. I’m a farmer at heart. I love farming. I think it’s a great thing, producing food and seeing the trees grow. The grass and everything else is great once you get out there, but getting up that morning to go out and do it was hard.

In Mississippi in the Delta they used to have something called frost. They even gave the frost a name. They called it Jack Frost. It would be cold in the morning and I never have liked a lot of cold. I see why I’m not white, because I could not stand the cold. I walk around now, I see people — especially white people — in their shirt sleeves and I can have on something heavy and still be cold. I get on the airplane and freeze. The stewardess come up, male or female, “May I take your jacket?” “Yes, please.” And then I’d freeze and go over and ask for it back. So I learned quite a few years ago, do not take off my jacket. Take off my overcoat but never my jacket, because you freeze.

Another place you go and you freeze is a casino. You go in a casino and they always keep it freezing. I don’t see how people can enjoy staying in there. So it was always something that bothered me and it still do today. I’m 78 years old and still cold blooded, I guess. Reptiles have nothing on me. I don’t want to bust nobody’s balloon but they could have kept the air conditioning as far as I’m concerned. I live in Las Vegas, and the temperature gets to be 110 — 115 sometimes — and I rarely have the air conditioner below 75. That’s generally my temperature that I like. I still like those old fans that blow the air. I like those and I’ll give you guys the air conditioners.

Where did you go to school? What was it like?

B.B. King: For about a year I went to a large school in a place called Lexington, Mississippi, but most of my early schooling was in a place called Kilmichael, Mississippi. Just outside of Kilmichael, about eight or nine miles maybe. My professor was a guy called Luther H. Henson, whom I love today. I truly believe that he was one of the few people that was able to get through this very thick skull of mine. Things he told us then was long before we ever heard of a Dr. King, long before we ever heard of integration, anything of that sort.

He said, “One day you won’t have to walk to school.” We had to walk five miles to school. “One day you won’t have to walk to school. One day there’ll be a central school,” he would say sometimes, “and everybody will go to that school. Some day nobody will look at you and think of you as a country boy or this if you don’t act like that. They will judge you by your deeds.” That was his words. “Whatever you do, however you do it will follow you the rest of your life.” And another thing he used to tell us — because we were sometimes, I think, a little hard headed – he said, “You have one body. Your body is your house.” I can hear him say that now. “If you take care of your house you can live in it a long time, but if you don’t take care of it…” meaning if you go out and you do things bad, like if you drink liquor, if you smoke, if you do this, you do that “…you’re going to hurt your house and your house won’t be able to last too long.” And you know, I started to smoke when I was 13 and after a while, I stopped. I started to drink and after a while, I stopped. Today I can still hear him; he’s been dead now a few years. He lived ’til he was about 102 years old. If I make 100, I’ll be lucky. But that’s the way I was as a kid and that’s the way I felt as a kid. I’ve never had a lot of friends like a lot of people, but I have a lot of acquaintances.

I enjoyed going to school. I wasn’t a very good student but I loved looking at the girls. I learned that early. That’s the name of my life story: “Loving to Look at the Girls.” I thank God. Creation of the ladies is the greatest creation ever. But we had one room where we’d sit at, and one teacher, and I guess there was about 40 or 50 of us, and that was the most of my schooling there at that particular school.

There was a lady that sat in front of me. I guess she was about eight or nine. So was I, but she was fully developed seemingly as a woman, heavy breasts and everything. We’d sit on pews. We didn’t have chairs. And about once or twice every month I’d get that urge — because I’d sit behind her all the time — to just reach over and grab her. My professor sat up on a little platform while we were studying, and he kept something called a “piss elm switch.” An elm tree has limbs that grow very long, and they don’t break easy. It was just like a whip. You would almost swear it was a whip. And they would sort of put them in the heater. We had a heater. We didn’t have central heat or anything. And they sort of burned it a little bit. When they burned it, it seemed to me the bark on the side of it was like leather. So when I’d get that urge and reach over to hug the girl — the minute I would grab her she would bite, and when she’d bite, he’d hit. So after I sat there for a while and get over that terrible pain, he would start to talk with us. It didn’t seem to bother him that he had already whopped me, but then when he would talk to me, for some reason, I understood him very well.

I really wanted to be a gospel singer. That’s what I wanted to be. This professor had a nephew that was a popular musician that played with a guy called Buddy Johnson. So when we would talk about music he would say to me, “You can do it if you want to. You can play music. You can preach. You can do whatever you want to do, but you’ve got to want to and you need a good education. You need to learn to do this.” He would say, “We live on a plantation, we’re in the country, and most people will put you down a little bit because you live in the country.” It’s true because when we would go to town people would say, “Here come them country people.” But, we did just the opposite. “There are them old city folks,” you know. My mother would take me to church, and this preacher in the church was named Reverend Archie Fair, we called him. Archie Fair was his name, and he played guitar in the church, so I wanted to be like him. And, I never really wanted to be a preacher, but I wanted to be a gospel singer, but my family thought that if I kept things up, kept going, one day I would be a preacher. Of course, I ain’t dead yet, so I don’t think it’s too late, but I’ve enjoyed doing what I’m doing for so long now.

You didn’t go as far in school as you wanted to.

B.B. King: No, I didn’t. I was lazy. I could have done better. My mom died when I was nine, and I lived alone from the time I was nine until I was 14, because my mom and my dad was divorced from the time I was five. And my mother had took me from the Delta back up in the hills, up to Kilmichael where we were talking about. Her people was from that area and my dad was an orphan and had been raised by some guardians in Itta Bena, Mississippi, near Brickclare Place it’s called. All this is in the area of the Indianola, which is where I grew up knowing about. But, I lived there after my mother died, as I said, when I was nine and she was 27. I didn’t know what was my wrong. My mother went blind. I could see the big blood clots in her eyes and she couldn’t see, but she would talk to me. I was the only child.

I liked working for the people that my mother worked for, the Cottledge family. I liked them. While I’m talking about that I’d like to mention that I have three people that I worked for growing up. Mr. Flake Cottledge, a man that I still enjoy calling Mr. Flake Cottledge, because to me he deserved it. I came to the Delta again, and this time on the plantation I worked for a man called Mr. Barrett, Johnson Barrett, and finally to Memphis where I met another person called Mr. Ferguson, Bert Ferguson. These three men have been in my life, and they still are, and I’ve said many times that if I could grow to be a man, I’d love to be like all three of them, just because to me each one of them was fair. They was good. They didn’t do things because they could do them. They wasn’t like a tutor or a teacher, but the things they said to me was like that.

When you were a kid working the farm in the Mississippi Delta, could you have imagined that Riley King would become B.B. King and that you would have this kind of life?

B.B. King: No. I never dreamed of it. My cousin and I would go out singing, wouldn’t get in until late. We’d sleep and they’d have a hard time waking us up in the morning to go pick cotton. Now if we don’t pick well, my uncle and my aunt — they’re not going to be happy at all. But we got to the place where we thought we was great. I think the most I ever picked was about 480 pounds a day, but my cousin was better. He would pick 500 and more. So we would pick a small bale of cotton every day, so they would let us sleep just a little bit longer because they knew when we come I was going to beat everybody else anyway.

I used to think then that when I got older, being that preacher and what have you, I was going to have me a little farm. Not a plantation, a little farm. I could picture seeing myself plowing, my mule or on my tractor. Picture seeing a beautiful woman with my two or three kids coming out, bringing me some water to the farm where I’m working at. I don’t want her to work. I want to work for her. I want her to come up and bring me my little kids, bring me some water or a piece of pie or something. Those were my dreams, not this. Those were my dreams, but when this did start to happen, and when I started to feel for real that I could do what I was doing, the way the people treated me, I was sort of like a guest at someone’s home. I don’t want to do anything to make them not be happy that they have a guest, me.

What did you do after you left school?

B.B. King: After the tenth grade I started doing like most kids do, not paying much attention to homework. I started going to do other things. Then I started to be what we call a regular hand on the plantation. Up there in Mississippi —I keep using the words “up there” because the Delta is around Indianola, Greenwood, Greenville. Past Greenwood going east you go into what we call the hills. Kilmichael is up there.

I used to chop cotton. I did all these things when I was seven. I was considered a regular hand when I was seven years old. I used to bale hay. I guess I did everything that farmers usually do and they expected me, the men expected me to do what they did and I did. And, I started to do more of it after I had dropped out of school because I made a little more money. Finally I learned — I was kind of into — today I guess you would say technology because I learned to drive tractors and I was pretty good. I had never heard the word “superstar” but when I think about it today, I was a superstar tractor driver. I loved it.

I loved it for several reasons. On Mr. Johnson Barrett’s plantation, we plowed the whole plantation. I’m going to try to find out how many acres of land he cultivated. I’ll tell you, you could ride 30 or 40 minutes and you still would be on his plantation. I mean doing 50 or 60 miles an hour, so you can figure out how much land that was.

But as a tractor driver I was popular. Hey, the girls look at you. I made a lot of money. I’ve been crazy about girls all my life. That was my downfall, I guess. It still is. But I made a lot of money. My salary compared to everybody else was great. I made $22.50 a week. I have chopped cotton for 75 cents a day. I’ve picked cotton for 35 cents a 100. When you’re driving a tractor, you’re sitting up there, all you got to do is use your expertise to keep it straight and don’t plow up the cotton, which I didn’t do too often because Mr. Barrett wouldn’t have put up with it. So you slept very well at night having to do that every day. My music and being a tractor driver seemed to make me popular with the people.

I wasn’t a bad guy. I’ve never been in trouble. I got put in jail one night after I was a man. I was speeding and they caught me down in the Mississippi Delta and put me in jail. I’ll never forget that. I thought about that every time I started to almost get in trouble. I didn’t like that place.

So how did you first become interested in music.

My great-aunt, when I was about six or seven used to let me play a Victrola. It was a turntable, and you’d wind it up and it would play a 78 record. I did see some records prior to that that reminded me of a cylinder in a car, and you’d slip a sleeve over it and the sleeve was the recording. I didn’t see too much of that. I guess it was a lot of trouble, but later on that was interesting to me. Very interesting. That’s why I went to Memphis. I wanted to record.

You didn’t just walk in the doors of Memphis and become a star.

B.B. King: Oh no. I had a good old friend that died not long ago. He said, “B.B. King ain’t no star. He’s a moon.” I doubt if I’m either. But no, I worked very hard to try to make people like me. I worked very hard. I’m kind of like the little dog that goes and gets the paper. He brings it back, you pat him on the head and say, “Nice doggie, nice doggie.” He’ll go back and get two the next time. That’s the way I am, and I try to do that even today. I try to be as nice as I know how to be. I love people. I’ll tell you something I don’t tell people often, but I believe all people are good. Sounds funny coming from a Mississippi boy, but it’s the truth. I believe all people are good. Just a very few do bad things. And you know what I believe? They couldn’t find a man like my teacher Luther H. Henson. I could listen to him and I could hear him, and I believe if those bad people could find someone — because there is someone out there I believe that they will listen to. I truly believe that.

Did you ever have any self-doubts about your ability to do this? Did you ever have stage fright?

B.B. King: You’re not going to believe what I’m about to tell you. I have stage fright today, 78 years now. I had a lot of confidence that I could do it. I’d hear Professor Luther Henson again saying, “If you try and try, try harder.” And I have worried quite often. People use —I don’t know where it come from, but if you try, nothing beats a failure, but a try. And if you try and you don’t make it, try and try again, and I believe that. I believe that today. I believe you — sometimes you may not make that mark that you was trying to get this time, but suppose you had ate too much, drank too much water or whatever. You’re just too heavy, try it the next time when you don’t have so much food, when you haven’t drank so much water, and that’s, I think, the way I believe even now.

Before I left home I thought I could really sing and play the guitar. I thought I was really good. When I got to Memphis and went down to Handy Park — at the time I think it was called Beale Street Park — and heard those people out there, it was like a community college on the streets! I found out then that I wasn’t so good as a singer. Oh, I thought I could sing, but nothing compared to what I thought before I got there and heard these other people sing.

I saw people dancing and I can’t even hardly walk. I ain’t never been able to dance in my life. If I had got a teacher or somebody that could have taught me, I could have been, but I never found anybody. So I got my book from Sears Roebuck.

How do you explain what you do? What is a blues singer? What are the blues?

B.B. King: Well, the blues have been put down. I had a cousin once named — he was the only person in our family that ever been popular as a blues singer. His name was Bukka White. Bukka never taught me to play. People say he did, but he hadn’t — or didn’t rather — but there’s one thing he did tell me that stays with me. It stays with me today. He said, “If you’re going to be a blues singer, a blues musician, always dress like you’re going to the bank to try to borrow money.” And, I didn’t quite get it, but what he meant is you don’t go there slouching and sloppy. Be at your best behavior and always try to be like that, and that stays with me today. This is sort of long, but my impression of what I get from people when they talk about blues singers, they picture a big black guy, like myself, sitting on a stool looking north with a cigarette hanging on the east end of his lip, a guitar that’s ragged laying across his lap, and a jug of corn liquor on his west side and his pants split on the south side. You still with me? A cap with a bib, and the bib is kind of turned up and sort of to the east again, and he’s looking north. That’s my impression of what I feel that a lot of people think of the blues singer. So, it’s been my life always to show that there’s a different blues singer, not just that one. But, I’ve thought many times if you’re black and you’re a blues singer it’s like being black twice, two times. I’ve always fought against that. Now that’s one thing I have tried to do.

I have learned that blues singing is just like singing any other kind of song. You still try to tell the story. Your story may not be as — shall we say — some of the love songs that’s written by a lot of the great singers, or great writers I should say, but you have a soul, you have a heart, you have a feeling and your music is life. Life as we’ve lived it in the past, life as we’re living it today, and life as I believe we’ll live tomorrow, because it has to do with people, places and things. If it’s a man, we think in terms of the lady, the opposite sex. If it’s a woman she thinks in terms of the man, but it’s still love, even though we call it blues. The myth is everybody thinks it’s all sad because it started from the slaves. That is a myth. Some of it is, but tell me what music doesn’t have some sadness in it, and then I’ll try to learn a little bit more about the blues.

Did it come easily to you? Playing the guitar and performing?

B.B. King: No, it don’t really come so easy. I think that I know my job pretty well, but I always think this way — now it’s not false modesty or anything — I’m never any better than my last job. Do you understand what I’m trying to say? In other words, I don’t always think that I’ve got it made and, “Hey, I’m B.B. King!” So and so. Never that. Never that because the people put you up there and they can cut you down like that. It’s just like the great God, this great spirit. We live and we die and I’m talking about if you die naturally you never know when it’s going to be. It can happen any time. So, I think in a way that we’re here — I’ve heard people use the word, “on borrowed time,” but I don’t know about that. I don’t think I borrowed it, but I think that I’m here and just as easy, cannot be here. So, I never think that I’ve got it made. I’ve known people that had a little money and overnight something happened — insurance no good — and what little money they had – bam – it’s gone.

I’ve known people to be happily married. I was twice. I don’t have a good education but I like to read a lot. Now since they got the great something called “computer” — Gosh, I don’t know how I lived without it! I was reading something on my computer, and some of it had to do with Mark Twain. Someone asked him, “Have you stopped smoking?” He said, “Yeah, many times.” Hmm. I’ve tried to lose weight many times. What I’m trying to say is that you really have to go head on and do it. Not many times, just once, and finish.

Who were your role models? Were there other musicians you learned from, who taught you things about music or life?

B.B. King: Yes, many. I knew Louis Armstrong. I knew Duke Ellington. I knew Benny Goodman. Those are just a few of the people that I tried to pattern my life after, after trying to be a musician. I still have that old code, don’t smoke, don’t drink on the bandstand, don’t swear on the bandstand where I am. Never. The people are the most important things that we have so you must treat them like they are who they are, and that’s the way I’ve been all the time, no drugs, no liquor. Even when I was drinking, don’t bring no liquor on the bandstand, never. That’s the way I’ve always been.

You’ve had to pay some dues along the way. You encountered some real setbacks.

B.B. King: I think I have. I’ve had tragedies. I remember once, after I thought I was doing pretty good — this is sort of hard. I haven’t talked about it a lot. After I thought I was doing pretty good, I bought an old bus. We called it Big Red. I bought that in 1955. The band would hop on that and we was doing pretty good. That year I think we did 342 one-nighters. Blues has never been a popular music like rock and roll or like jazz. I always use the words, “We seem to be at the bottom of the totem pole all the time.” My guarantee, I believe, was about $250 a night, and we needed the money. We were young at that time and didn’t pay much attention to what we were doing, no more than we were going places. Moving about, we introduced the kind of music that we do. I hope when they come they’re surprised and they’ll hear it and like it and they’ll come back again.

Well, at that time then we thought it was a great thing to have a bus. The band would be in the bus and I’d have my car. You had to have a new car, especially a Cadillac. You’d tell everybody you’re doing great when you didn’t know whether you were going to eat the next morning. Look like what you ain’t. If people think you’re doing well, they’ll support you well. That was our thing.

One particular day I had played in Monroe, Louisiana, on my way to Dallas. So, I had gone to visit somebody. My bus left at the time it was supposed to. Later that evening I came on, on my way to Dallas, and found out that my bus had been involved in a wreck. It had ran head on with a butane gas truck. It had burned the front end — the whole front end off of the bus. None of my people was killed or hurt, I should say except the driver. He had broke his toe trying to get out of there, but a man had been killed in the accident and another one had burned badly. I didn’t see them. I wasn’t there. I didn’t know about it. And, the same day, would you believe, during that time the Senate was — I forgot the word they call it — but when the big conglomerates and insurance companies, when the big ones get — they had started to tear them apart if you know what I mean. I think they did it to AT&T and a few other companies. At that time, that very evening, I get a letter from my insurance company telling me that the insurance was terminated that very day, and this is like on a Friday. So, I got Saturday and Sunday, then come Monday before I can get more insurance, but I’m already on the bus, the bus now done burned up, a man has been killed! Like I said, I wasn’t there to see it. It still cost me, and they claimed there was a lady that caused the accident that was coming up to one of them Texas bridges. And in Texas, even then they didn’t have the super highways like we have today, [but] you had ballast on this side, something that if you hit it you would skid back over this way or back this way, and it was raining. So, the bus tried to miss this lady in the car, and then hit that ballast, and when he did, that’s when it bounced back right in the path of that oncoming butane gas truck. It hurt me so bad. I didn’t know what to do, but then they sued me. They didn’t care nothing about it. It was a million dollars. One million dollars! I ain’t never even seen — I couldn’t even spell a million! God, a million dollars. That was one of those times when you talk about paying dues. It took me a few years to pay it, but they let me pay it off. But, luckily the lady had good insurance and a great lawyer, so we were lucky to get a pretty good lawyer that worked with her lawyer, and they got it down to a million. They wanted much more, but we had to pay it off. That was my first setback.

Was there a turning point in your career?

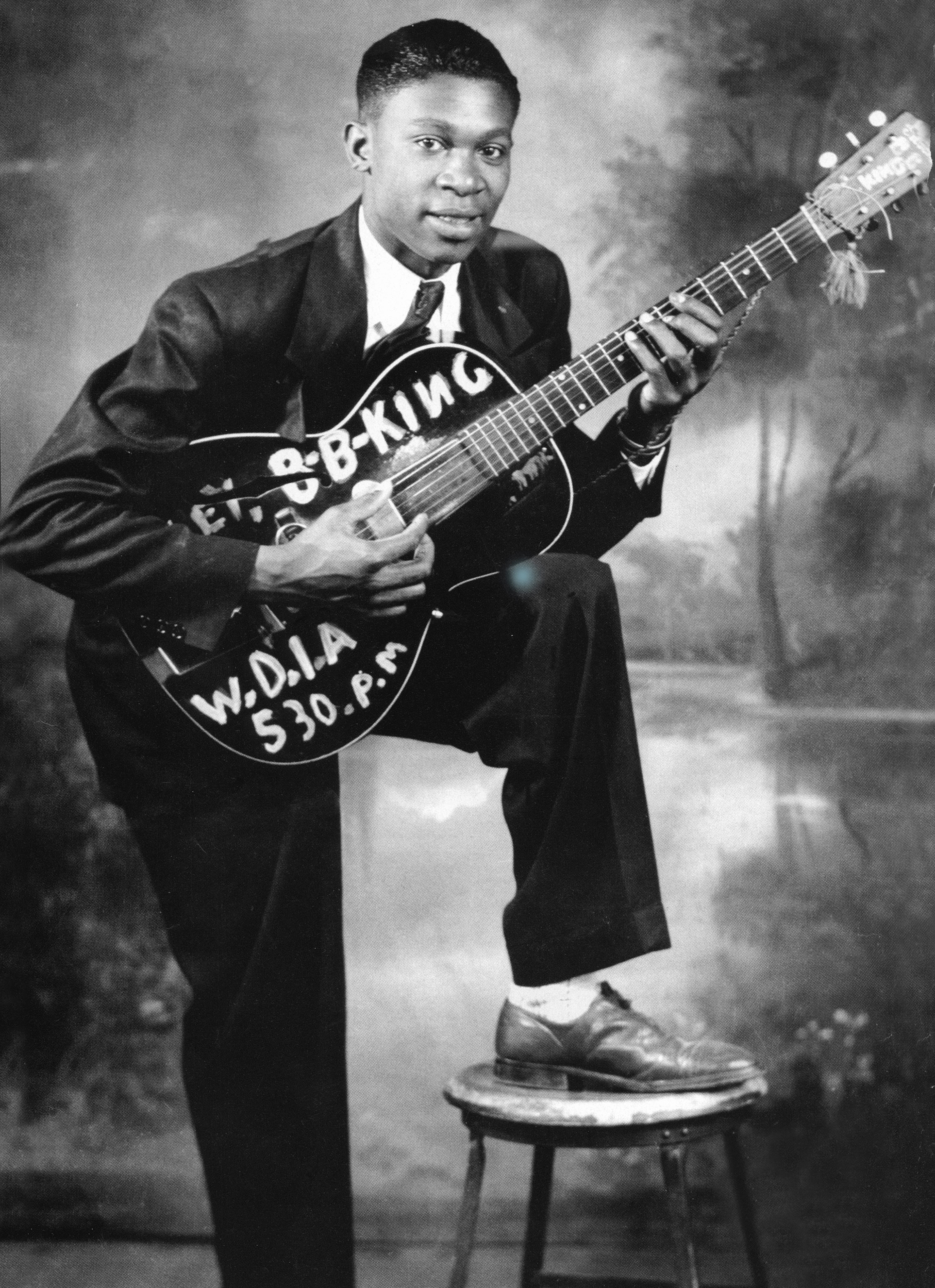

B.B. King: Well, let me start it off like this: I was with a small label, and to sell 100,000 copies of anything was a hit for them. So, I got a telegram from my company that said that, “B, you got a hit.” I had recorded several things, and this one was called “Three O’Clock Blues.” They said, “You have a hit.” So then the people in the area of Memphis — because I had been on the radio, I was a disk jockey there from ’49 to ’55 — “You got a hit,” they’d say. So, I would go as far as I could go (and still) get back to the radio station the next day. And when I learned about transcribing or recording your program earlier they would let me do it sometimes. I was becoming very popular, but it was mostly then black because we were — remember — still behind the Mason-Dixon Line and the only people that were allowed to come and see me were black. And usually my audience was my age and older, but I was a young guy then. I was in my 20s. Then as I got older so did my audience, and they stopped coming, the black ones. Then long after that I started hearing people talk about my guitar playing. I never heard it from the people that the journalists said talked about it. I always would hear it from a journalist. “Somebody said so-and-so said you can really play.”

One day I was reading a magazine — at this time the Beatles was the hottest group I ever heard of and I guess anybody else — and I read where John Lennon was being interviewed and the interviewer asked him what would he like to do and he said, “Play guitar like B.B. King.” I almost fell out of my chair just reading it, and I didn’t believe it, but I had a producer at the time named Bill Szymczyk. Bill knew John. So, one day we was in New York recording, and John was in town and he talked to Bill. And Bill said, “You got a guy over here that’s real crazy about you,” and told him who I was and I spoke to him. I never seen him personally, but I talked to him for about five or ten minutes. I was just so happy to know there is a man that’s the most popular in the world that knows my name — not my music, just knows my name — and I felt good.

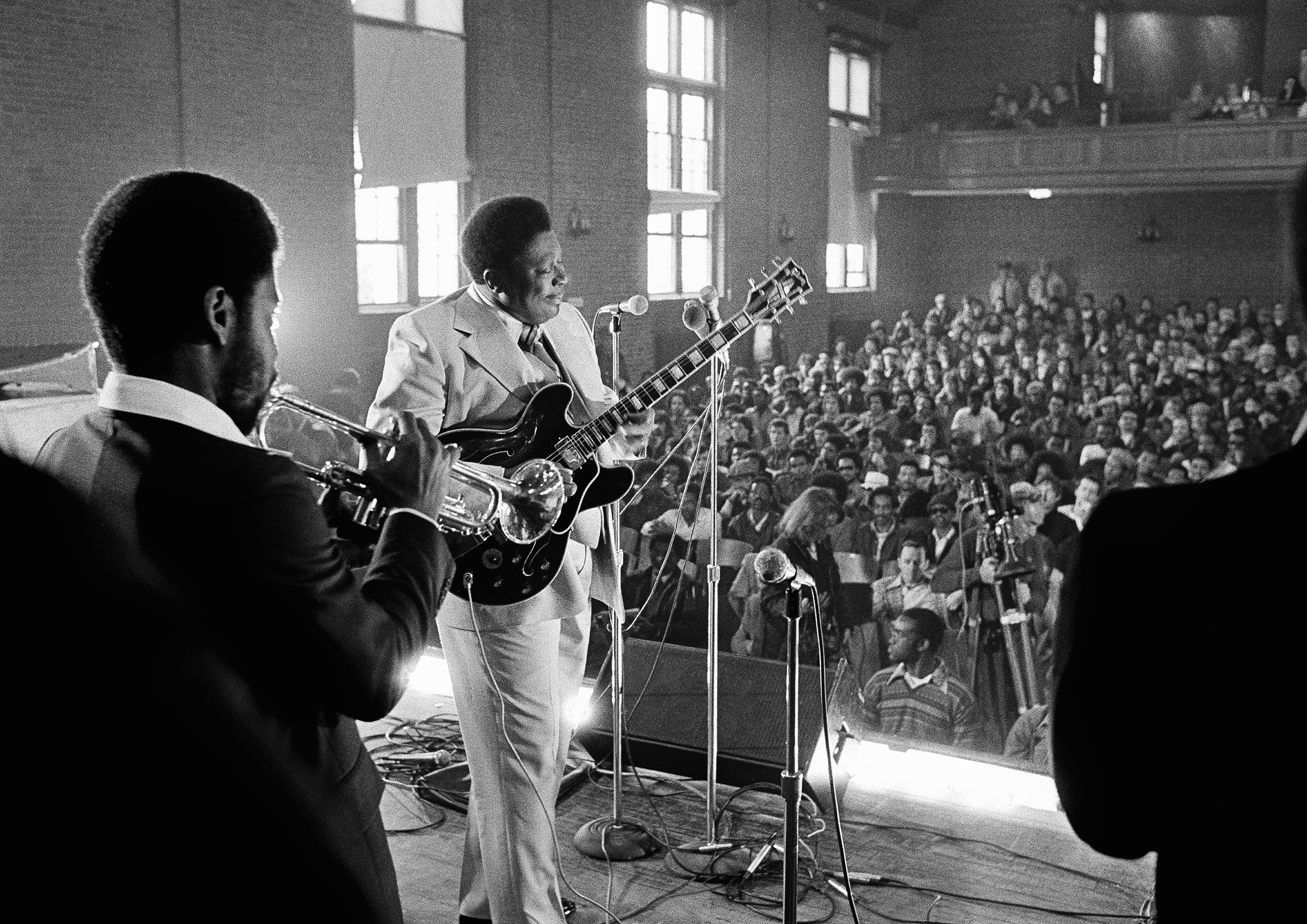

Now, we started to pick up a different audience. Instead of the black audience that we had, we now were getting young white people. Now, I’m traveling about. Now, I’m going to San Francisco. I’m going to small places all over the United States. Then finally, this agency that I mentioned to you earlier booked me at a place called the Fillmore West. Now, I had played the Fillmore many times before when it was owned by another person, but this time when I get there, there are long-haired kids — kind of like Jesus Christ used to have, long hair. I had never seen people wear hair like that around me. I saw it in papers, books and the Bible. When I pulled up there we were still on this bus. This is before the accident, this Big Red as we called it. We looked out there at the Fillmore where we used to go and in the stairway leading to the door there was people sitting from here all the way across, and there was about three or four stairs that lead up to the door. The stairs was about as long as the average length of a regular car and they’re body to body sitting there. So, I told my road manager, I said, “I think they made a mistake this time. I don’t think we’re supposed to go here.” I said, “The band and I are going to sit here. You go in and find out what the mistake is.” So, my road manager went out and he found the promoter — who was Bill Graham, one of the greatest people I think I’ve met — and he came out and said, “No, B, it’s the right place.” I looked. I wanted to say, “Are you sure?” And he said, “I’m the promoter. Come on in.” I’m scared to get off the bus. I said, “Okay.” So, I followed him in.

Now as we went inside, and this may not seem like much to you, but I’m used to when you go in past people and they’re sitting body to body, they move way over and they’re going to look at you and say, “Hey man, watch it, don’t step on me.” They didn’t do any of that. They just sat there, and the ones who was having a conversation continued. They just leaned over politely and said nothing. And here I am like this, scared as I could be. I ain’t never played for nobody like this.

Now when we finally get through these people on the stairway, we get inside, there’s no tables. Just a big ball room. Bare. No tables. No chairs. Nothing. People now are sitting body to body on the floor. I said, “Oh my God, we got to get past them.” This way and that way. And then finally we got to the old dressing room that I had been used to going to. I looked at Bill and I said, “Bill, I got to have a drink.”

He said, “B, we don’t sell liquor here.” “I don’t care. I got to have a drink.” He said, “Okay. I’ll send out and get you one.” He sent out and got me a half a pint of something. I don’t know, but they brought it to me and I had a big belt of it. And I sat there reminding myself of how a cat would be if a dog was in front of it. I’m scared to death. So, Bill said, “I’ll come back and get you when it’s time to go on.” I thanked him and sat there, still shaking.

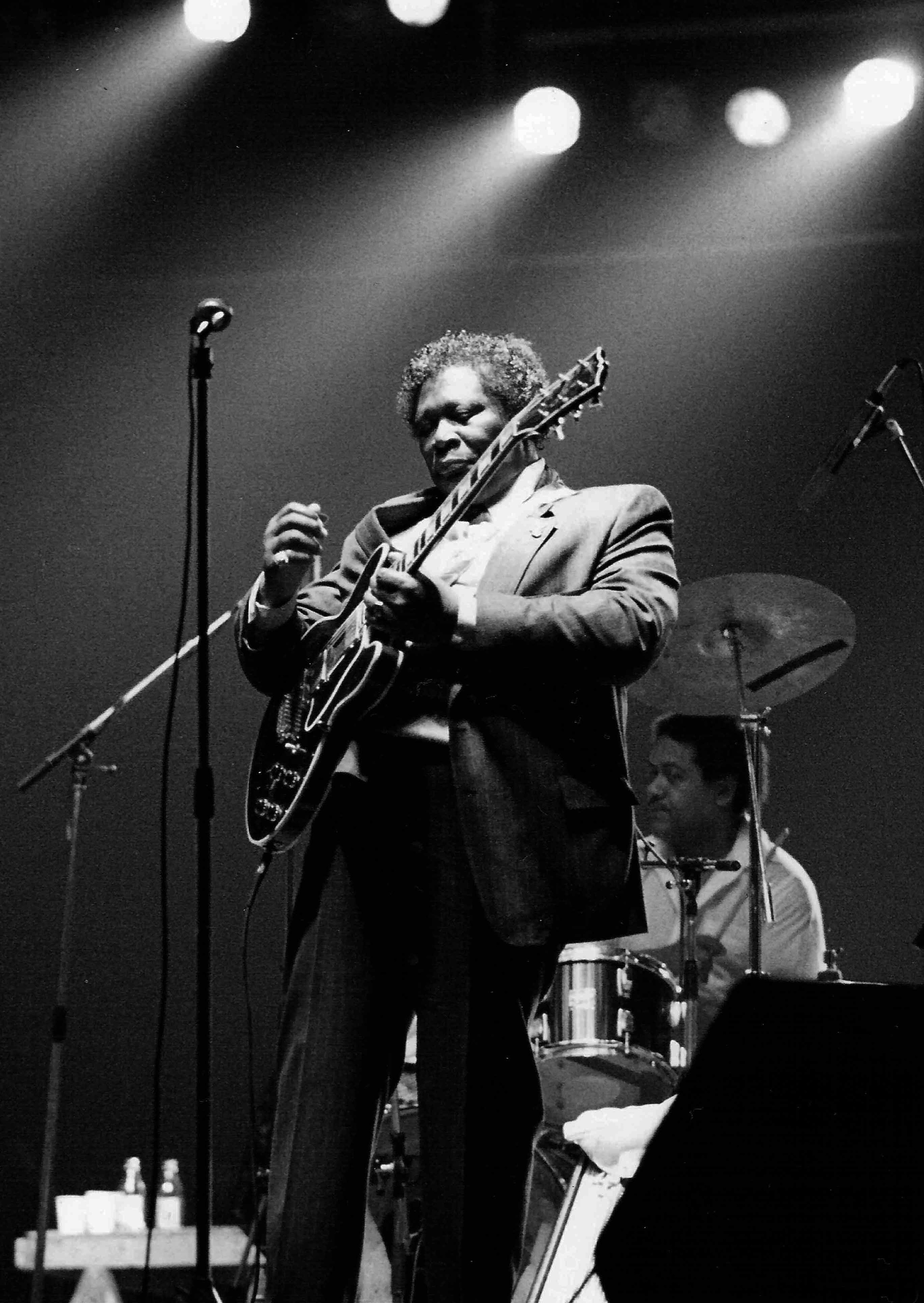

When it was time for me to go on stage, he [Bill Graham] came back and got me, and we got to wade back through these people again, but when we got to the stage — see, they don’t know me by looking at me. They don’t know what I look like. They only know me by the music. He said, “Ladies and gentlemen…” and everybody got very quiet “…I bring you the Chairman of the Board, B.B. King.” The best intro and the shortest I ever had in my life. And all of a sudden they started to applaud, and they stood up and they applauded and I cried because I’m starting to think how these people can be so good to me and what the heck am I going to do for them. I ain’t never played for no people like this. Well, I quite often perspire quite a bit. Perspiration is running all over me, but I was crying too, and I think I had about a 45-minute set. Do you know they stood up two or three times more? And that’s the first time that I ever thought that I was doing pretty well. Not really made it, but I had gotten pretty close to the door.

What was it about that audience that frightened you and that moved you to tears?

B.B. King: They were young. Hardly 30 years old most of them.

So it was a breakthrough for you?

B.B. King: It was a breakthrough for me. They didn’t seem to look at me as B.B. King, the blues singer. It was B.B. King, the musician. They made me feel like I was somebody. I had never felt like that. Never. Oh, I had been treated nicely. Don’t think I hadn’t. But this time, the way they treated me made me think that I was like some of them other people I heard of, like the big stars. They made me feel like that that night. I’m standing up there crying because I’m so moved by what they’re doing, and then I’m wondering what the heck am I going to do for them.

How do you account for the fact that you could do it? Not everybody who comes from where you came from gets to where you are.

B.B. King: I don’t know how to answer you. I’ll try. There is so much to do. So much more to do till even today. I think that I’m okay. I think I know my job. I said this earlier. I have had a lot of things happen to me for which I’m grateful.

I’ve met four sitting Presidents: President Ford, President Bush, Sr., President Clinton and President George W. Bush. I call him “young President Bush.” Then I met the Pope, and gave the Pope a guitar. I met the Queen of England. A few words to the Queen. I was scared to death because I didn’t know the protocol, the etiquette and everything. I didn’t want to do nothing wrong. But about a month ago I met the King and Queen of Sweden, and they gave me something called a Polar Prize. To me that’s the highlight of B.B. King’s career.

I’m grateful for being awarded six honorary doctorate degrees. I’ve been honored at the Kennedy Center. All these things to me has been great, but it ain’t something like you can put in your pocket and keep it. It was great. Oh God, what a wonderful time, but I’m so glad it’s over when it’s over. Do you understand what I’m trying to tell you? Glad to get it, but oh God I prayed it was over. All of these things is important to me, yes. I’m so glad it happened, yes. But that was them. I’m meeting these people. That’s not B.B. King. They’ve given me honors and stuff, that still don’t tell me that I’ve done anything. It means more to me than I know how to tell you, but it’s me meeting you, meeting her or him. The honor is I’m being able to meet them.

When young people come to you for advice, what do you tell them?

B.B. King: I think I would go back to what my teacher told me in a way, but quite differently. I would say, “Get high off your music. Don’t use drugs of any kind. Please don’t smoke because that will mess up your vocal cords for your singing. Be a person. Just as you want to be loved, love them. Always respect the people that come to hear you play. Try your best to please these people, but then you’ve got to live in the neighborhood. Try to be a good neighbor. Play your music. If you’re a student, if you’re going to college, major in music, minor in computers so if your music don’t work you can still have a job. Lastly, you might become very good at what you do, a lot of people do, but everybody is not going to like it, so if you can’t make a living at it go back to your minor.” That’s what I would tell them.

We’ve enjoyed your talking with us.

B.B. King: Thank you, sir.