Why was school desegregation so difficult? Why was it such an emotional issue?

Frank Johnson: School desegregation? White people did not want their children to sit with, eat with, get acquainted with, play with black children. It was something that had never been done in this section of the country. It was an emotional thing. Some black parents had some emotional problems about being required to send their children to predominantly and formerly all-white schools. So it wasn’t just on the white side.

The head of one of those school boards said that segregation was necessary “to separate good people from bad people.” Do you remember that?

Frank Johnson: No, but I’m not surprised that some superintendent said that.

And the Chief Justice of Alabama, I believe, said that he would do anything in his power to keep his kids from “going to school with colored people.”

Frank Johnson: I don’t remember that. The Chief Justice of the state? That may be true, but I don’t remember that.

Did you come up against a lot of opposition in those days?

Frank Johnson: Sure. I still get opposition. When you have litigation, you have two sides. When cases involve legal questions that are important enough to litigate in the federal courts, you rarely ever have a case without some kind of emotionalism in it.

Do you have to separate your own emotions to do your work?

Frank Johnson: I try not to get my emotions involved in any lawsuit. I don’t ever remember being personally emotional or having emotional feelings in any lawsuit. It’s not my lawsuit. It’s their lawsuit. All I’m here to do is determine what the law is, and then apply it. If you take that approach, there is no basis for getting emotional.

Were these decisions fairly clear-cut to you, or did you have some real conflicts?

Frank Johnson: I had no problems with desegregation cases. Discrimination on the basis of race is basically unconstitutional. I don’t care whether you are on a bus, or anywhere else. You run into some problems when you get into genuine private clubs, but that wasn’t what we were involved in. I respect the right of people that want to have private organizations. I think they have the right to do that. But when the organization reaches the point that it becomes a public organization, then the blacks have a right to come in.

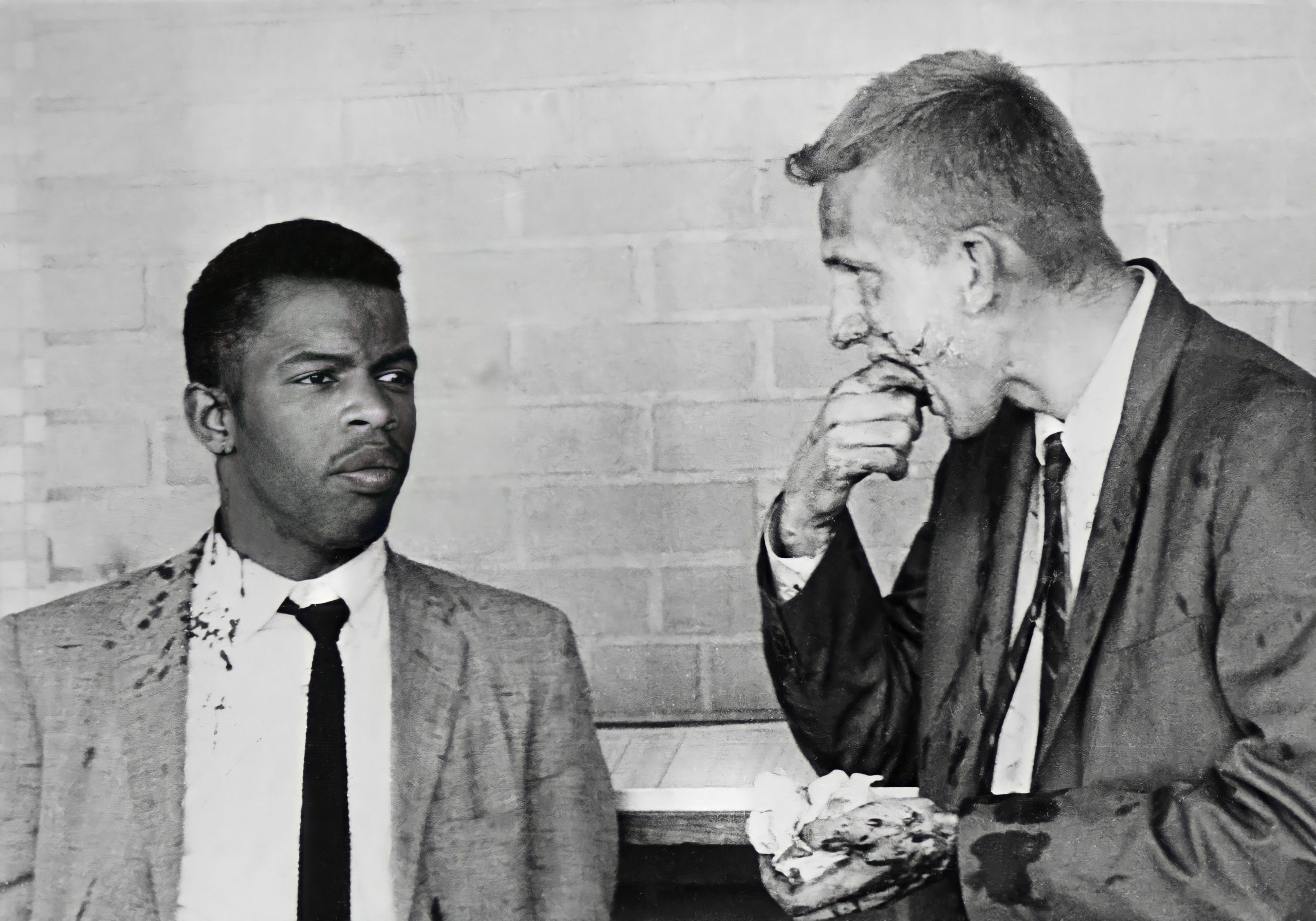

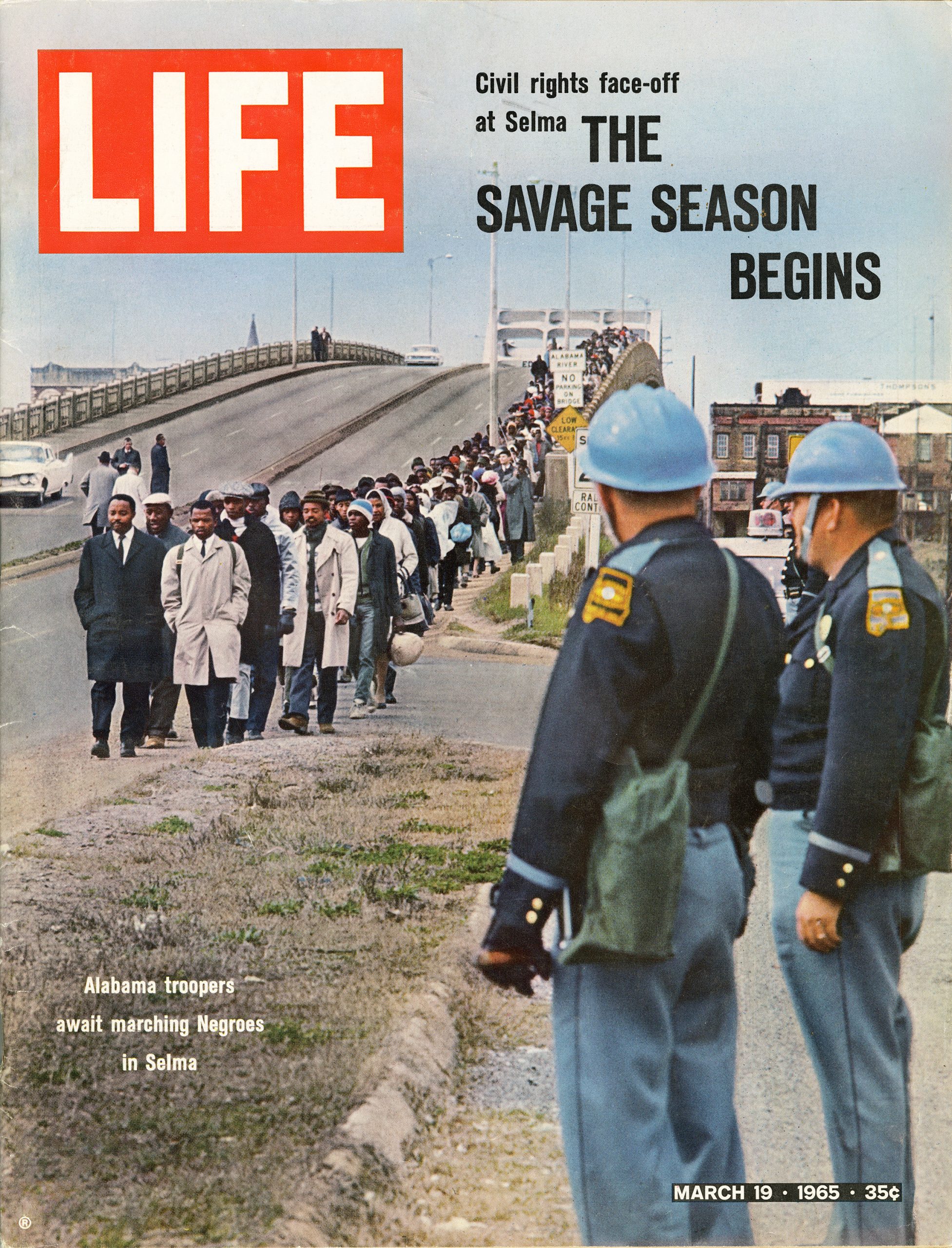

I’d like to talk about the Viola Liuzzo case. Who was she? What happened to her?

Frank Johnson: I didn’t know her, but she was some lady that came down here from Michigan, drove her own car to participate in the Selma march. The facts that came out after she was killed revealed all of this. I had never heard of her, but after the march from Selma to Montgomery, a lot of these people — and there were thousands of them — didn’t have any way back to Selma. She was using her car to take them back.

What race was she?

Frank Johnson: She was white. She had just taken a load of people back to Selma, and she and a young black, about 15 or 16 years old, were coming back to pick up another load.

These Klansmen, that were down here to see what they could do, to intimidate or something, had been here to Montgomery and watched the march some, the marchers coming, and then they went to Selma. They saw her, or met her, as they were going to Selma, and she was coming back here with a young black sitting up front with her, with a Michigan tag on, and they turned around and took after her. Of course, the Klansmen didn’t realize that one of the people in there was an FBI informer. That’s the reason we knew all about it. He had been an FBI informant for years, and a member of the Klan. The FBI had informants in every Klan. Stupid if you don’t, you know. You don’t know what’s going on, you don’t know what’s going to happen before it happens. So, the FBI informant that was in the Klan car reported it, as to who did it, and I tried them, right here in this courtroom.

They had already been acquitted of murder in the state court, hadn’t they?

Frank Johnson: That’s right. The only thing they were charged with here, after they were acquitted in Lowndes County — the state prosecution — public places in montgomery.was violating her civil rights. They were convicted. They got the maximum: a ten-year sentence. That’s what the statute was. I gave each of them a maximum sentence. They appealed it. One of them died while the appeal was going on. I’ve forgotten his name. But the other two served their sentences.

Isn’t it kind of a euphemism to “violate someone’s civil rights” by murdering them?

Frank Johnson: That’s right. The federal government doesn’t get involved in basic criminal laws. That’s still left up to the states. We have a federal law that prohibits you from murdering the President or federal judges, but not just an ordinary citizen on the state highways. That’s not a federal violation, except violating civil rights. That’s the only thing they could charge them with in the federal court.

The jurors didn’t reach that verdict immediately. Could you tell us about that train of events?

Frank Johnson: I don’t know how long they stayed out. I don’t know what goes on in the jury room. All I know is what goes on in the courtroom. They brought back in a guilty verdict.

Didn’t they first say they were deadlocked?

Frank Johnson: Oh yes. That’s not unusual for a jury foreman to come back in and say, “Judge, we’ve been deliberating this case six hours now, and we can’t reach a verdict. We are deadlocked.” I say, “You haven’t been discussing it long enough. Go back to the jury room.” I said, “It took several days to try this case, you go and stay in the jury room.” Sent him back. I think I sent them back two or three times. They didn’t want to return a verdict. Some jurors were scared. You had the Klan as defendants. They were being asked to convict Ku Klux Klan members. They were scared of them. But they did. I gave them the maximum sentence. Ten years. One of them died even before he got to the penitentiary. The other two served their sentences.

You said afterwards that this was the only verdict the jury could have reached.

Frank Johnson: That’s right. It was the only verdict they could have reached and do what the oath requires them to do.

There was plenty of evidence?

Frank Johnson: Oh yes. A lot. They didn’t even testify. They would have had another ten-year sentence for perjury.

You eventually called for the desegregation all public places in Montgomery. How did that come about?

Frank Johnson: After the bus decision was affirmed by the Supreme Court, the restaurants and the other public places voluntarily consented. They didn’t put it in the paper, but when the blacks went in, they served them. We didn’t have to enter any other decisions. I don’t remember another desegregation case. Because the affirmance of our case was by the Supreme Court of the United States, and it had the effect of desegregating public transportation all over the United States. Other areas had some of that desegregation, not just the South. I think Auburn University turned down a black student, he filed a case, and I ordered him admitted without even a trial, on a motion for summary judgment, we call it. He came back later and said he wanted a place in one of their dormitories. I ordered the university to do that. The last report I had, he was the only one living in the dormitory. He had a lot of room, a private bath. But all that’s over now. They welcome the blacks at the University of Alabama, all of the public education places. I don’t know of any segregation problems we have in this section of the country anymore.

United States v. Alabama, in 1959, was a voter registration case which led to national reforms. Can you tell us what that case was all about?

Frank Johnson: That was about discrimination in registering to vote. Black people were not welcome to register. Each county had a Board of Registrars, and they gave examinations and they were very difficult. They used different standards for grading them. When Mrs. Johnson and I moved to Montgomery, in 1955, we had to go to the Board of Registrars and take a very complicated examination. The case finally came to my court, and after taking evidence in the case, I decided that I needed to determine the standards that were being applied by the boards in registering whites, and then issue an injunction requiring they apply those same standards to black applicants. Well, it turned out that there really weren’t any standards. An illiterate white could go get registered. And that’s what we wound up doing. Registering every one that comes, if they are a citizen.

This decision brought a lot of criticism from your old classmate at the University of Alabama Law School, George Wallace. What did he say at the time?

Frank Johnson: He said things to the papers, the TV, the radio, and anyone who would listen. He was running for governor. He was a politician. He has recognized and publicly admitted that he used some questionable methods. He has apologized for those. He has health problems now (1991) and I am not going to go into any details about Governor Wallace. But he has apologized publicly for everything he did. And I’m sure he’s asked for forgiveness privately.

How did that case affect national voters’ rights?

Frank Johnson: It had a tremendous effect, particularly in the South. When you put the registrars under an injunction, telling them they must apply the same standards in evaluating applications to vote by black people that they’ve been applying to white people, then if they don’t start registering the blacks the same way they do the whites, they are in contempt. So all you have to do down here in this section of the country now is to go to the Board of Registrars and sign up. You don’t have to fill out these big, long, stupid forms.

You also ruled against the state’s poll tax. What was your reasoning there?

Frank Johnson: Well, the right to vote is a basic right in this country. It is one of the basic rights that a citizen gets, and I ruled in that case that you shouldn’t be required to pay to vote. That’s what it was. I declared it unconstitutional. Wiped it out. I don’t think we even heard an appeal in that case.

What was the poll tax all about? What were they trying to accomplish?

Frank Johnson: I don’t think it was enough money to make up much of their budget. It was just another hurdle to exercising basic rights.

Were they specifically trying to keep black voters from registering?

Frank Johnson: And poor whites. It was just as bad on them as it was on poor blacks.

You also issued the first order for reapportionment in American history. Didn’t that in some ways anticipate the Supreme Court?

Frank Johnson: I never decided cases trying to anticipate what the Supreme Court is going to do. Never.

Can you tell us about that case?

Frank Johnson: It just tried to make representation in the state legislature on a just basis instead of on an unjust basis.

It was ridiculous here in Alabama, because back when the apportionment was established, your owners of these big farms down here, previously successors to the slave owners, they owned the most land, and they had the least population in the county. It discriminated against these counties up in north Alabama that had a lot of population. You might have 25,000 people in a north Alabama county, and they just had one member in the legislature. You’ve got 3,500 people in a county down here and they had one member in the legislature. So let’s put it on a basis of population, instead of on land.

Why hadn’t anyone done that before?

Frank Johnson: Well, we’ve made a lot of progress in the last 50 years. People didn’t challenge the political establishment. They were afraid to. It cost money to do it. So you went to some of these legal organizations for taking on those cases. In some instances, private lawyers did it. People have become conscious about their basic constitutional rights as a citizen in the last 35, 40 years.

Is the concept of civil rights and human rights that recent?

Frank Johnson: It’s been a part of our constitution since it was first set up, but it wasn’t implemented until the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s.

You’ve said that you hoped most people in the South grew to support your decisions, and believed it was the right thing to do, even though they themselves might not have been able to speak out. Do you think that’s the case?

Frank Johnson: I think it’s reached that point now, that they accept rulings that guarantee equal rights to black people, and expect them. They realize that it’s something our Constitution requires. It had to be, otherwise you are going to have to go back and revoke their citizenship. They have the same rights as a citizen of the United States as a white person. There is no way you can justify a position that differs from that.

Where do you think your own urge to serve the public good came from? Why stick your neck out as far as you have?

Frank Johnson: I don’t consider having, quote, “stuck my neck out,” end quote. I value the decisions that I’ve made and the effect of those decisions. I did it not for my benefit, but in the first place, I did it to decide the issues that were presented to me in legal cases that came up routinely through the system. My oath as a United States judge required that I decide cases like I think the law requires it to be decided. So, technically you had no option if you are going to be a good judge. You do what you agreed to do.

It seems you had a very strong pull toward public service.

Frank Johnson: If I’d been working for a law firm, I think I would have had the same attitude. It wasn’t just because I was a public servant. It was because I had a job to do. If I’d been working in a steel mill, I would have done the same thing: what my job requires be done.

You’ve said in previous interviews that growing up in Winston County probably had an influence on your career. How so? Could you give us some history of the place?

Frank Johnson: Well, when the Confederacy seceded from the Union, Winston County passed a resolution at a public hearing over at Loonie’s Tavern in the eastern end of Winston County, seceding from the state of Alabama and reaffirming their allegiance to the United States. I’ve always been proud of that. It was a good thing to have done. Had I been there, I would have attended the conference and refused to secede from the United States. That’s the history part. People in Winston County generally are very independent, they think for themselves. You don’t have any rich people up there, you have poor people. It’s in the hills of northwest Alabama. No big cities there, some towns, a lot of farmers, and their standards are very basic. That’s where I grew up.

You’ve used the expression “frontier justice.” What does that mean?

Frank Johnson: Well, I consider the expression frontier justice to be justice that is demanded by individuals, demanded by groups, without being enjoined or mandated by a judicial body.

Did you feel a sense of that there?

Frank Johnson: Oh, yes. Most of those people did.

Were any of your relatives or ancestors involved in public service?

Frank Johnson: My father was a county judge. That’s when I decided I wanted to be a lawyer. I used to go and sit in the courtroom, and watch him try cases, watch lawyers argue.

Wasn’t there also a great-grandfather who was a sheriff?

Frank Johnson: You’re talking about Treadway. He’s buried up there in Walker County, down at Carbon Hill, which is just a mile or two from where the old Treadway-Johnson farms were. He had some basic philosophies. When the South seceded from the Union, he went up to Decatur, Alabama, the closest Union group, and enlisted as a member of the Union Army. One of my relatives on the other side enlisted as a member of the Confederacy. So, they fought on both sides. But in each instance, they were doing what they thought was right.

Your great-grandfather had a nickname, didn’t he?

Frank Johnson: Yes. It had something to do with his character: “Straight Edge.” He was a farmer and raised horses. He had his own horse track, and they raced horses. Don’t ask me if they bet on them; I don’t know that. I would guess they did. That was their weekend entertainment. Big farms, no money, a lot of work. I didn’t come from a rich family, I came from poor families.

They made him sheriff, didn’t they?

Frank Johnson: Oh, yes. Sheriff of Fayette County. The Klan gave him a hard time. My family had been opposing the Klan for over 100 years when I came down to Montgomery. They got someone that was hard to intimidate. Can’t do it.

How do you suppose your background in Winston County, the example of your father and your great-grandfather, influenced your own decision-making process as a judge?

Frank Johnson: The basic concept that a good judge has to have is to do what’s right, regardless of who the litigants are, regardless of how technical, or regardless of how emotional the issues that are presented are. If you are not willing to do what’s right, then you need to get you another job. So I never did think that I was entitled to any great credit for doing it, because that was my obligation. That’s what I signed on to do. Some judges didn’t do that, but that’s their problem.

When did you first have an inkling of what you wanted to do with your life?

Frank Johnson: When I was 12 or 13 years old, sitting in the county courtroom up there in Winston County. Watching these lawyers. Watching the judge. Sure, I wanted to be a lawyer ever since then.

Why? What excited you?

Frank Johnson: Oh, it was exciting. They were advocates. They advocated and presented positions. Whether they agreed with them or not, they represented their clients. They were hired to do that. They were professionals. Very interesting. Fascinating to me.

Was it the sense of drama that takes place in a courtroom?

Frank Johnson: Oh yes. All trials have some dramatic aspects to them, some more than others. We’ve tried some big ones in this courtroom. Big ones. I’ve had Klan members sitting all over, in the balcony and everywhere else. They come to intimidate you.

You laugh, but they did some pretty vicious and violent things.

Frank Johnson: Well, I was laughing because they were wasting their time when they tried to intimidate me. They realized that and it didn’t continue for several years.

Were you already interested in being a federal judge when you were in law school, or was it something that just happened?

Frank Johnson: No. I was interested in being a good lawyer. I didn’t lie in bed and dream at night about being a judge. That just came. You can’t plan that. It’s something that happens. You have no control over it. One of the ironic things is that the judge that was here for 23 years before he died in 1955 was from north Alabama also, and a Republican. His name was Kennamer. His picture is out there in the hall. So we’d had Republican, north Alabama district judges here in Montgomery for 50 years when I went on the Court of Appeals.

Did the people down here in Montgomery see you as kind of a foreigner?

Frank Johnson: Oh yes. Sure. The newspapers sponsored a lawyer down here in Montgomery for the position and he didn’t get it. So they were saying, “They went up to north Alabama and got that foreigner!” That was the Montgomery Advertiser. They didn’t support me very much for ten, 12 or 14 years because of that.

Just because you were from elsewhere?

Frank Johnson: No, I don’t think they liked my philosophy. Changing some of the South’s customs and standards. For instance, one of my first cases… when a black pays their way to ride the public bus, they shouldn’t go up and pay and then go back in the back door and sit in the back of the bus. They pay the same amount that the white people pay. They are American citizens. Let them go sit where a seat’s available, where they want to sit. That’s just basic as far as a public transportation case is concerned. But that’s what they were doing. That’s the first injunction that I entered after I got down here that came up and was presented. A judge doesn’t reach out and get issues. It has to come up through the court system and be presented in a formal manner.

How did your parents react to your choice of career?

Frank Johnson: I think they were proud when I decided that I’d be a lawyer, go to law school. They supported me 100 percent. I didn’t come down to Montgomery to practice law. I practiced in north Alabama.

What did they think when you started making those controversial decisions?

Frank Johnson: After I became a judge? Supported me 100 percent. As long as you think you are doing what’s right, follow the law, and the facts require it, you have to do it. If you are not willing to do it, get another job. They didn’t articulate that, but that was their philosophy.

It must have been very helpful for you to have that kind of family support because you were in some tough spots.

Frank Johnson: Well, my wife came from up there too. She was born and raised up there in the country in Winston County, and she felt that way. So I have no problems as far as my immediate family is concerned. I may have had some cousins that wouldn’t admit that they were related to me, but I guess that happens to all judges.

Was there any time in your early life that you thought about being something other than a lawyer, or was it always clear?

Frank Johnson: Oh, when you start growing up, all children want to be policemen, but you are talking about third, fourth, fifth grade, or something like that. After I got out of high school, I had in my own mind decided that I wanted to practice law, be a lawyer.

What about the law inspired you to devote your life work to it?

Frank Johnson: Well, I could see how much pleasure the people that practiced law seemed to get out of it. It’s a pretty dramatic occupation. You make your presentations in the courtroom, evaluate your position, decide which issues you are going to pursue and which ones you are going to abandon, if any. Then make your presentation to the judge if it’s a judge’s trial case or the jury if it’s a jury case. I think practically all lawyers — not all of them, but most of them that have the training and do trial work in the courtroom — enjoy it. I get that impression. Otherwise they would do something else. Because it’s hard work. It’s not easy. A lot of pressure.

Is it fun?

Frank Johnson: I don’t know if “fun” is the right word. It gives you an impression that you are doing what’s right. Gives you some personal satisfaction when you do it successfully, even though it’s not your case, it’s someone that hired you to present their case.

Is it the sense of really having accomplished something?

Frank Johnson: That’s true. Absolutely. Whether it’s a big case or a little case.

As a lawyer, how did you deal with loss, when you didn’t win? Or did that ever happen?

Frank Johnson: No. It did happen! A lawyer who has practiced law for a long time that tells you he’s never lost a case is lying to you. You don’t win all your cases, because you don’t make the facts. You can’t tell how jurors are going to decide cases. Sometimes you can’t tell how a judge will decide a case. So if you practice law any length of time, you will win some and lose some. You get a lot of satisfaction out of winning, but you look to your next case when you lose one. You shouldn’t feel bad about losing it if you do the best you can with what you have. If you goof up, and don’t do the best you can, then it’s time you backed up and evaluated yourself and what you are doing. But if you practice law, you don’t win all cases. The best surgeons in the country lose patients.

Was there a particular person in the law that inspired you as a young person?

Frank Johnson: Other than my father? Yes. I had a lawyer that had been a state circuit judge up at Jasper, Alabama, by the name of James Curtis. He wasn’t too much of a trial lawyer. He didn’t like the courtroom too much, but he was a great lawyer. I agreed to practice with him when I first started in law school. I got out of law school right before I left to go to World War II, and he paid rent on chambers for me that were adjoining his chambers for three years until I returned. He was a great, great lawyer. We worked on Saturdays, locked the door to the office, did our briefing. He knew the law well enough to say, “Frank, this issue was discussed in such and such a case. Get that book, 342 Alabama Reports.” Just great. He was in his late 70s then, but his mind worked beautifully. We named our son for him, James Curtis Johnson.

What made him a great lawyer?

Frank Johnson: Dedication. Studying. Integrity. Those are three things that are basic requirements. It takes a lot of studying. A lawyer that doesn’t study loses cases. He embarrasses himself. He undermines the profession.

Were you hard on lawyers who showed up unprepared in your courtroom?

Frank Johnson: They say that! I was fair with them, because of their clients. If I was just dealing with the lawyer, I would have ejected them from the courtroom. But their clients selected them, and they are entitled to have a lawyer represent them. But as long as he comes to court, he has certain standards he is required to meet. I required that.

What do you think Mr. Curtis saw in you?

Frank Johnson: Dedication. I was willing to work, willing to study. After I was there two or three years, I tried all the cases in the courtroom. He used to sit at the table with me. He did not make oral arguments. He didn’t question witnesses. He was there to help me with strategy. Once, it was a big case, jury trial. When I had completed the final closing argument in the case, he whispered to me, “Frank, that’s the best argument I ever heard in my life.” He was 80 years old. Just great. Inspires you. One of the nicest things that I’ve ever had said to me. He was a good trainer. He was someone who caused you to do the best you can, and try to meet the standards that he stood for.

Were there any particular books that inspired you as a young person?

Frank Johnson: I can’t remember any specific book. I read a lot of books. If I had any inspiration, it was from people, not from books.

What about teachers along the way?

Frank Johnson: I had some great teachers. I had some bad teachers. Everyone does, I guess if they go through the public school system. There was one we called an old maid — she was about 65 — named Ada Drake. She was tough, she was hard, but she was fair. She inspired me. My father sent me off to the military school after I got to be a little maverick when I was in about the tenth grade so I could get a little discipline. I had some great professors down there.

What did Miss Drake teach?

Frank Johnson: Mathematics. I was great at mathematics. Very poor at algebra. Algebra was goofy, and I still believe that. Because I’ve never seen anyone use algebra for anything. But I was great in mathematics. Enjoyed it.

Do you think that influenced your sense of order and organization?

Frank Johnson: Maybe, yes. My mother did a lot of teaching at home when we were young. She and my father both were school teachers. That’s where they met. I remember learning the multiplication tables. I don’t know how old I was, eight or nine. Very easy, very easy. No problem. It was a little harder on nines, but very easy, I enjoyed mathematics, but I despised algebra. Still do.

We’ve spoken to a lot of athletes who say they were attracted to the idea that if you work hard towards something, you can accomplish something, and it’s very concrete in sports.

Frank Johnson: That’s true with everything. The result probably is a little more concrete in sports. I might have to wait ten years to realize that this mathematics course I took was good for me. I accomplished something when I did well in it. You realize that when the season is over in sports. But I guess the most important thing about sports is you have to depend on other people and they have to depend on you. So you start working with people and not against them, whether you like them or not. If they are a good football player, or a good basketball player, or good baseball player, you respect them and you depend on them, they depend on you.

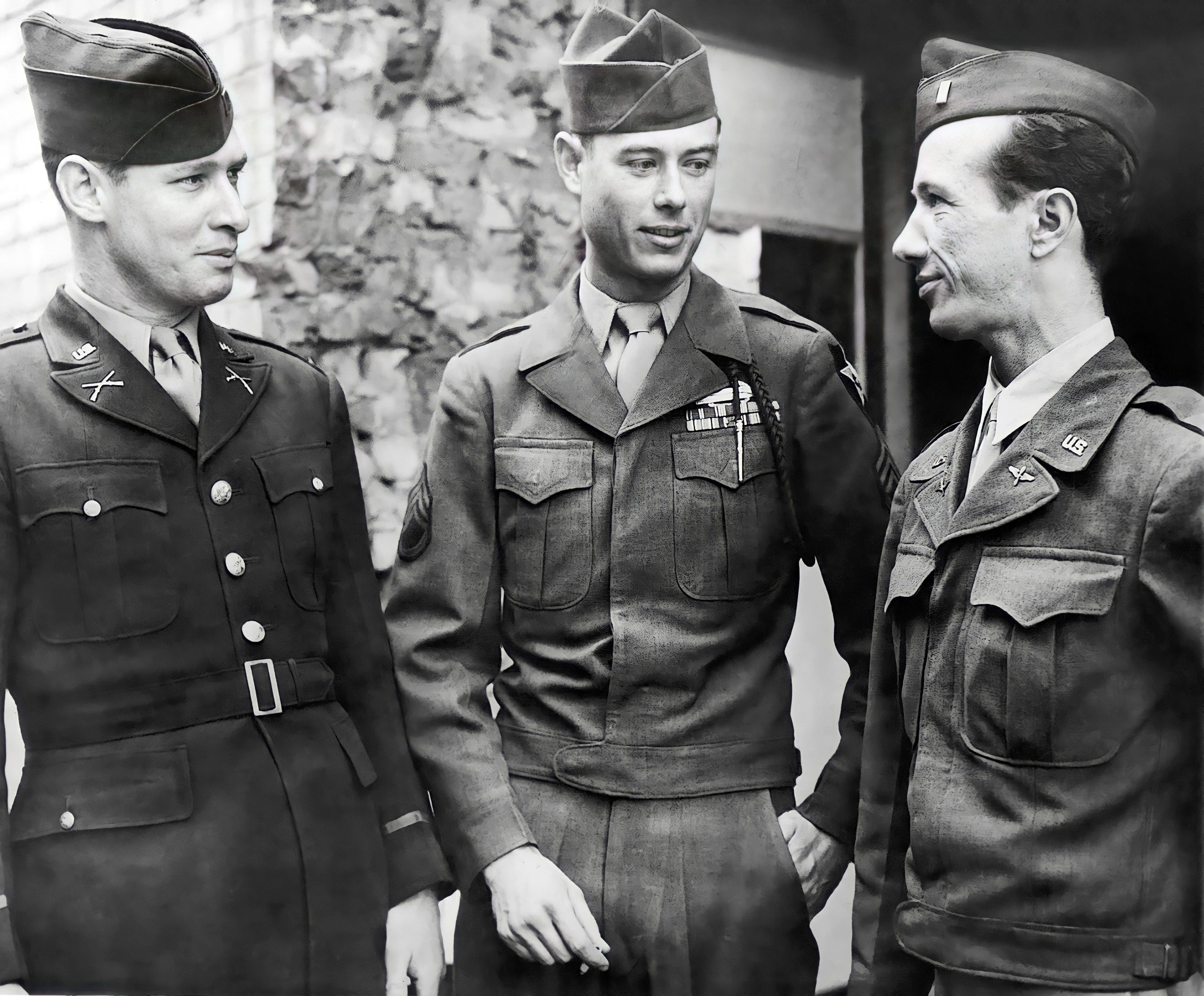

We understand that you were involved in the Normandy invasion. Could you tell us about that?

Frank Johnson: I wasn’t in the first or second, or third (wave). I went in two days later. But they weren’t 300 yards from the beach. So I was in the Normandy invasion in that sense. I helped get through Saint Lo. After we broke through Saint Lo, we went across France. I was in Patton’s Third Army. I was a lieutenant in the infantry. I got shot once in Normandy, stayed in the hospital 11 days, went back still with the bandage on. They left the bullet in there. It’s still there. They said, “It will take you three months if we operate and cut it out,” said “You can get back in ten days if it stays in.” So they filled it full of that stuff that was just out, what did they call it then? Powder? Pat you on the rear and you get on back to your crew.

Can you still feel that bullet?

Frank Johnson: No. It’s between two muscles. I still have a hole. Doesn’t bother me.

Were you aware of the historical importance of that invasion when you were a part of it?

Frank Johnson: Of course. Everyone was, I suppose. We went back to Omaha Beach this past summer. It was Mrs. Johnson’s first time she had been there. The first time I’d been back. Walked down all the way to the water, across the beach. It’s still there. It doesn’t look as dramatic this time as it did the last time because there weren’t a thousand boats out there. But we enjoyed going back.

Are there still some remnants of the battle there?

Frank Johnson: Yes, a few. Mrs. Johnson wanted to climb up on one of those German bunkers. It may be one of the ones I helped take. I took her picture up there waving an American flag.

You must have felt a great sense of pride to be part of that.

Frank Johnson: After it was over! After it was over.

Was it frightening when you were actually doing it?

Frank Johnson: Sure, you’d be stupid if you are not scared.

Looking back on your career as a judge, what role do you think luck or fate has played in your life?

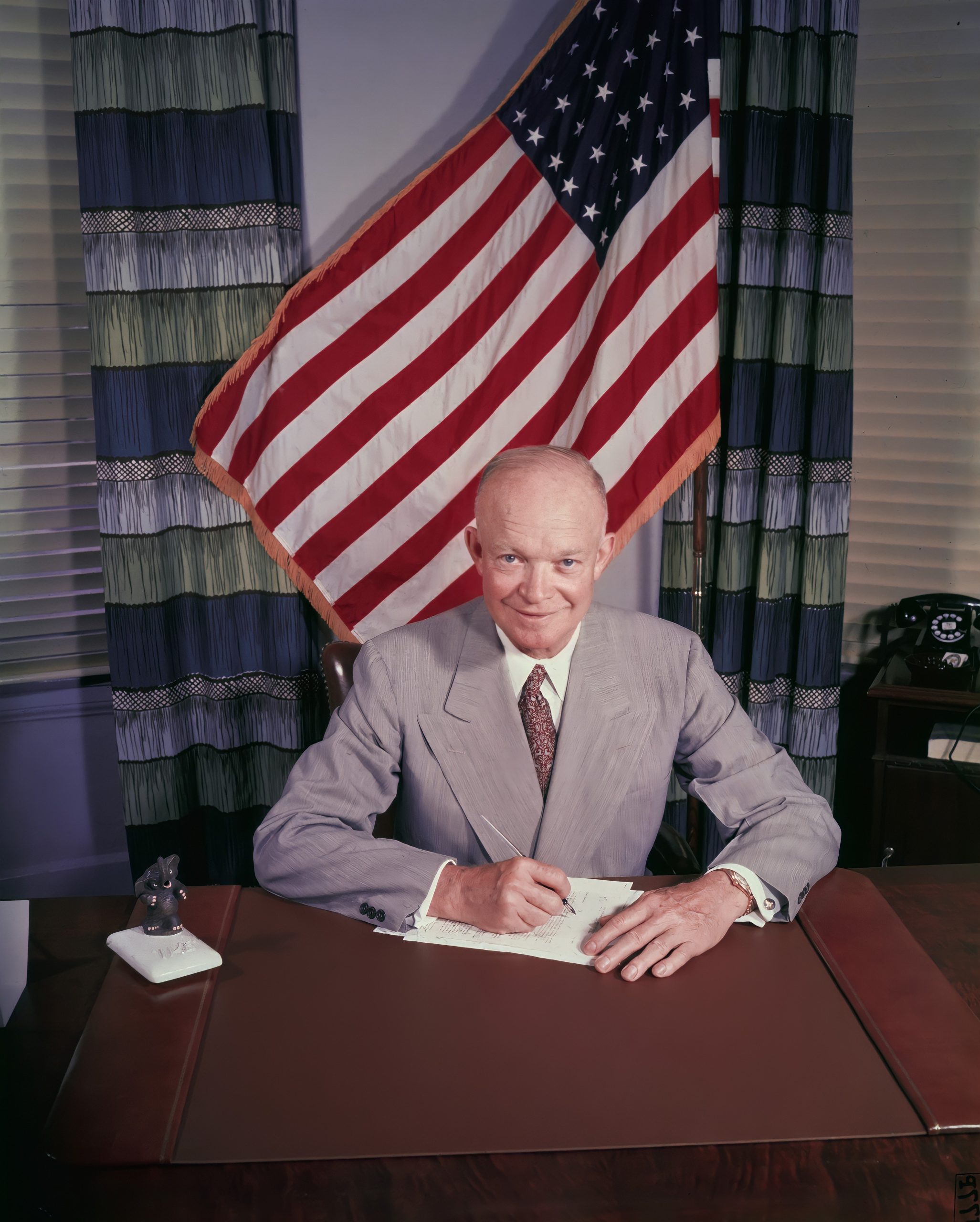

Frank Johnson: You don’t buy, or work for, or aim for federal judgeships. You have to be in the right place at the right time, with the right qualifications. There are a lot of great lawyers that wanted to be federal judges that were not in the right place at the right time. I was. I didn’t plan it. It’s something you can’t plan. When I was practicing law, President Eisenhower wanted me to be the United States attorney in Birmingham. I agreed to accept it for two years, because I didn’t want to leave my law firm any longer than that. At the end of two years, the district judge here, Judge Kennamer, had died. I stayed three more months because my name was being mentioned. I never did go back to my firm as a lawyer. I moved from the United States Attorney’s office, as United States Attorney, down here to district judge.

What do you think made President Eisenhower choose you?

Frank Johnson: In 99 percent of the cases, judges are appointed because they are in the right place at the right time, and associated with the political party that controls the appointments. My people had been Republicans since the Civil War, so I met those qualifications. And age-wise, I was a successful trial lawyer, had practiced considerably in federal courts in north Alabama, Birmingham, Huntsville. So, I was in the right place at the right time.

What kind of work did you do for Eisenhower in his campaign?

Frank Johnson: I was his state manager for Veterans for Eisenhower.

Do you think he was rewarding you for your efforts on the campaign?

Frank Johnson: I doubt if he ever knew that. No. The Republican Party knew it, and they are the ones that made the recommendation. Eisenhower didn’t know me until he was ready to appoint me. He would not appoint anyone a federal judge unless he met them and talked to them personally. That’s the first time I ever met him. All of these soldiers tell you about seeing Eisenhower and getting acquainted with him while in Normandy. That’s hogwash. You don’t do that with a four-star General. The first time I ever met and talked with him was in the Oval Office.

What was that like?

Frank Johnson: He was interested in the qualifications of everyone he appointed. He is the only president I know of that set up the rule. There may have been some sense then that they would never appoint one unless he had met them and talked to them. So you had to go to the Oval Office for an interview. He took a lot of pride in the people he appointed to federal courts. And he appointed some good ones.

You’ve mentioned seeing Ku Klux Klan members sitting in this courtroom. What was that like?

Frank Johnson: Well, they didn’t wear their uniforms, or whatever they call them, bed sheets. Your FBI knew a lot of Klan members. I kept a list of every Klan member in every Klan in my desk, still have it. Knew who they were. Knew what business they were in. Knew what the tag number on their automobile was. And when they come to court, you know who they are. They have a right to come to court. Sit, watch, listen.

What cases were they here for?

Frank Johnson: Oh, a number of cases, any of them that involved segregation or desegregation, the right to vote. Basic rights cases in which they had an interest. When I put the Klan under an injunction, they had the right to come.

Why did you keep a list of all the license plates and stuff?

Frank Johnson: I wanted to know who they were. I wanted to know who I was dealing with when I was dealing with jurors. I checked my jury list to see how many Klan were on the jury, so I would know who they were. You want to know what’s going on. I did.

When it came time in the ’70s to deal with mental hospital reforms and prison reforms, you made a point of not visiting those places. Why was that?

Frank Johnson: That’s right. I don’t want to go see all those people lined up there in bad places.

What was going on in the mental hospitals that you felt was unfair?

Frank Johnson: I didn’t have any feeling about how the state mental institutions were being operated until the evidence was presented and I considered it. After I did consider it, it became obvious to me that they were being treated in an inhuman manner and in an inhuman environment. They have a constitutional right, not one to keep from being put in a mental institution, but if the state puts them in one, they have to put them in an environment that doesn’t violate their constitutional rights. That’s what the case was about, and that’s what the decision was about. You either stop running a state mental hospital — stop operating one — or operate one according to what the appropriate standards are. They couldn’t stop operating one; a state has to have a mental institution. So the only option they had was to comply with it. I had experts that inspected them, and they set up the standards, and those are the standards that I followed in requiring the state to meet. I’m not an expert in prisons. I’m not an expert in mental hospitals. But I can evaluate experts’ testimony.

What were these experts saying?

Frank Johnson: They brought pictures. They said the patients weren’t getting any treatment. All they were doing was being incarcerated with no treatment.

Conditions were pretty awful, too, weren’t they?

Frank Johnson: Yes, they were. They put those young people up there in Partlow, where their arms were tied, and all that sort of stuff. The place had flies all over it. I saw a picture of a little girl with flies all over her face with her arms tied. Scandalous. Scandalous. But Alabama is not the only state that did that. You had other states, not just Southern states that did the same thing. But this case down here set up the standards that were later adopted nearly all over the country. Not just in the mental hospitals, but in the penitentiaries, too.

Didn’t Governor George Wallace say you were trying to make a prison into a hotel?

Frank Johnson: That’s politics. He knew better than that. He said a lot of things about my decisions that were just for political purposes. He knew better than that. He’s apologized publicly for all of those statements.

As we touch on these decisions over the past 36 years, it’s becoming increasingly clear what a profound effect some of your decisions have had on all kinds of institutions. How do you react to criticism that you’ve been too intrusive as a judge? That you’ve intruded on state government?

Frank Johnson: I don’t resent that kind of criticism. If some person is consciously convinced that I’ve been too intrusive, then they are entitled to that opinion, and they are entitled to articulate it if they want to. But before it has any effect, they are going to have to be a federal judge and have the authority to make that decision.

Do you take that criticism personally?

Frank Johnson: No. Sure don’t. I get criticism now for ruling in a death penalty case, or affirming a district judge in a school case, but on the appellate courts, you do not have to make the initial decision. So the public is not as sensitive to who is making the final decisions as they are to who makes the initial decision.

You once said that you are not easily ostracized, and that’s part of your personality.

Frank Johnson: That’s right. I’ll do my own ostracizing. You can’t ostracize me, because I do the ostracizing. There are some people that I wouldn’t fish with if they were sitting on the best fishing hole in the country. Other people, I’d like to go fishing with whether we are going to catch any or not. I’ll do my own ostracizing. It’s hard to ostracize someone that does their own. And I’m thankful for it. My wife feels the same way. She’s from Winston County too.

Didn’t she ever wonder if you were making too many unpopular decisions?

Frank Johnson: Oh no. She never criticized any decision I ever made.

In 1978, another unpopular ruling was the “reverse discrimination case” at Alabama State University. Could you tell us about that?

Frank Johnson: That’s the Alabama State case. I wrote the opinion in that case, blacks discriminating against whites. It’s just as bad, just as illegal and just as unconstitutional, if they are doing it in the operation of a public institution. Discrimination against whites by blacks is just as unconstitutional as whites discriminating against blacks. So it ought to be applied the same way.

What was the case about?

Frank Johnson: It was about the Alabama State University operation which is a black institution. I don’t remember the details or the facts.

A white man said he was discriminated against.

Frank Johnson: That’s right.

What kind of reaction did you get to that case?

Frank Johnson: Maybe some criticism by some blacks. Maybe some black lawyers that represented the Alabama State institution. But I didn’t pay any more attention to that than I would from the whites.

As a federal judge, you are insulated from the pressures of having to be reelected.

Frank Johnson: That’s right. I would not ever have accepted a state judge’s job, because you can’t do your job without being subjected to political reparation. It’s the only reason I accepted this job.

Because you’re more independent in this job?

Frank Johnson: Independent as you want to be. Some federal judges still think their social status is very important. But that’s their problem. It makes their job harder. The job is hard enough without regard to that, trying to figure out what’s right and what’s wrong.

You had a close call with being the Director of the FBI.

Frank Johnson: Close call? I almost died. Is that what you mean?

No. Just the fact that you almost became the Director of the FBI.

Frank Johnson: I was appointed Director of the FBI, and went through the members of the Senate, and didn’t have a single opposing vote. Just about that time, I went for a physical examination, because I was having to give up a life salary, and I needed to buy four or five hundred thousand dollars worth of life insurance. The physical examination showed that I had an aneurysm here about the size of a lemon. They sent me to Birmingham to the university hospital two days later, and it was the size of an orange. By the time I got to Houston Hospital in Texas — they operated on me the next morning after I got there — it was the size of a grapefruit. They gave me a picture of it. Saved my life, that appointment as Director of the FBI, saved my life. After about a month, I realized it was going to take me two or three or four months to get through, and I asked the President to withdraw my nomination so they could get someone in there because they needed some leadership. He asked me who I thought, I told them to call Bill Webster. And Bill accepted it. So after I got well, I went back to work, the President called me — in ’78 I guess — says, “Will you take a place on the appellate court?” I said “Yeah, I will.”

What was it like dealing with Jimmy Carter? What was he like?

Frank Johnson: He is honest. He is open. He’s straightforward. He will always tell you the truth. He may not be the smartest president we ever had, but I would expect he is as honest as any president we’ve ever had. He might not be the best politician in the world, but you may find it hard to be a very effective politician and always do what’s right. That may have been what his problem was. I have a lot of respect for him. Not because he appointed me, or offered me anything. I wasn’t looking for an appointment. One Saturday afternoon, I was out in my backyard, mowing my grass, my wife came out and said, “There’s a call on the telephone.” I said, “Tell them I’ll call them when I get through mowing. I’ll return it.” She said, “Well, it’s from Jimmy Carter over in Georgia.” So I went in and took it. He wanted to know if I could come to Atlanta and talk with him the next day. That’s the first time I ever met him. He wanted advice about some appointments. Someone he could talk to and trust. That was before he asked me to be Director of the FBI.

Do you have any regrets about not being able to take over that post?

Frank Johnson: Director of the FBI? No.

You also were suggested by the Nixon administration as a possible Supreme Court justice.

Frank Johnson: Several times. Don’t have any regrets about that. Why regret it when you can’t do anything about it? I don’t lie asleep at night, or lie in bed not able to sleep because of something that I can’t control.

Returning for a moment to your brush with death. You were the patient of a great surgeon who is also a member of the Academy. Could you tell us a little bit about your impressions of Dr. Michael DeBakey?

Frank Johnson: He’s a great man. At that time, he was probably the most outstanding surgeon in the world. First time I was ever out there, three or four days after he operated on me, he said, “I’ve got to go to China. So and so will be in here to see you, two or three times a day. I’ll be back in five days.” He had to go operate on someone in China. Took his whole staff. I’ve been out there several times. He’s operated on me four times. These arteries in my legs, this dacron aorta I have in my abdomen. We got to be good friends.

He’s a person of tremendous accomplishment.

Frank Johnson: Oh, yes. A man of high integrity, too. I’ll guarantee you that. He’s dedicated to his work. I didn’t know him when they found this aorta problem. I came back from the University Hospital in Birmingham, my doctor was at my home. I asked him, “Where is the best place in the world to go? And I don’t want a second class doctor. Who is the best?” He says, “His name is DeBakey.” I said, “Get him on the telephone.” He got him on the telephone. DeBakey says, “Sure. But tell him to come now. Those things can burst.” Mrs. Johnson and I got on the plane the next morning. We were out there at 3:00 in the afternoon, and spent that time until midnight running me through examinations. They operated on me at 5:30 the next morning.

You felt you were in good hands?

Frank Johnson: Sure, yes. Nothing I could do about it. He had a reputation for being the best one in the United States.

Looking back on what you have accomplished as a judge, what advice would you give to youngsters who might be interested in pursuing this line of work?

Frank Johnson: Study. Be honest. Don’t violate the laws and get in trouble. Get you a good spouse that will support you, because you never stop working and studying. The fact that you get the place just means you’ve started as far as the work and the pressure is concerned. That’s the only advice I’d know to give.

What qualities do you think make the difference between someone who achieves and someone who doesn’t achieve?

Frank Johnson: Hard work, if you’re talking about people of equal qualifications. Hard work. I don’t care if you are a federal judge on the appellate bench, or if you dig ditches for a living, you have to work hard to do a good job. That means you can’t just walk in a courtroom and not know anything about a case. You have to study it before you go, and when you get out, you have to study it before you write an opinion. You can’t just walk in without working. You can’t walk out without working. It takes work. You have to be dedicated in order to do it. That means you ought to get into some kind of business you like, because it’s easier to work hard. It’s easier to do a good job if you like it.

I don’t guess you look back and see a lot of drudgery in your life.

Frank Johnson: No second thoughts. Even if I saw it, I wouldn’t admit it. Nothing I can do about it.

As a judge, how much importance do you attribute to sheer instinct, a gut feeling?

Frank Johnson: None. Not when you are an appellate judge. None. Because the record is already made. The issues are already formulated. The law, in most instances, exists that controls the issues that are presented. So it’s just work. Nothing innovative about being an appellate judge unless you have some case that comes up that there is no precedent for, and nothing to bind you.

So instinct has not played an important role in your career?

Frank Johnson: No, shouldn’t play any, and as far as I know it hasn’t played any, as far as my judicial career is concerned.

When you look at the criminal justice system today, do you still see injustices that you wish would change?

Frank Johnson: I think we’ve made a lot of progress in the last 20 years in the criminal justice system. Back when I first became a federal judge, there was no basis for paying a lawyer that you appointed to represent an indigent defendant. So you had to appoint lawyers that were willing to do it. Some of them — if you appointed — and they were real busy doing something else, they put it on a back burner, and (the defendant) did not get proper representation. I required the United States Marshall here to pay a young lawyer that I had appointed to defend a person for the expenses — not pay him his attorney’s fee — but the expenses that he incurred personally in representing this indigent defendant. The U.S. government got real excited about it; I didn’t have any authority to order the Marshall to do it, and it got to the Justice Department. They requested the Congress pass a bill paying expenses to lawyers that represented indigents. And then it wasn’t a year before they passed a bill that authorized judges to pay lawyers that were appointed to represent indigents. A minimum type of fee, but that’s how it got started.

It seems like there is still racism inherent in a lot of institutions. Would you say that’s true?

Frank Johnson: Yes, sure would.

Is that ever going to change?

Frank Johnson: I don’t know. You are going to get discrimination to some degree, on and off, not consistently. You can’t take the humanity out of a human being.

One writer said that your willingness to do the right thing has led you on “a long odyssey into the dark side of the human spirit.” Do you feel that the human spirit is dark?

Frank Johnson: No. I’ve seen some people whose human spirit is dark, but you are talking generally. No. I operate on the theory that most people are basically honest and want to do what’s right. If I didn’t believe that, I don’t believe I could get along. Unless they prove otherwise to me, I’ll operate on that theory. I intend to keep doing that.

Over the past couple of decades, you’ve denied repeatedly to journalists that you are any kind of crusader for what’s right, and yet you’ve been given credit for tremendous changes in this country.

Frank Johnson: I’m not a crusader in the decisions that I’ve rendered while I’m a judge, for this reason: I did not make the facts, and in most instances, I did not apply law that didn’t already exist. How can you be a crusader when you are not doing anything except taking the facts that someone else has created, and apply the law that exists?

The legal profession gets a lot of bad press these days. There are a lot of bad lawyer jokes, and so forth. What would you say to encourage someone to pursue the legal profession?

Frank Johnson: I wouldn’t try to encourage them to pursue the legal profession unless they had some inclination to get in it, or some interest in it, and were genuinely inquiring with an open mind as to whether they should. And then, until I knew and talked to them, I wouldn’t encourage them. There is nothing worse that happens to a person than getting in the wrong profession. And I think 99 percent of the people can determine the profession they want in without anyone encouraging them or discouraging them. Make up their own minds.

What is so exciting, as far as you are concerned, about the law? Why has it been such a tremendous source of fulfillment for you?

Frank Johnson: Because it’s so important to the continued existence of our society. We can’t continue without laws, and without application of laws in a nondiscriminatory manner. You could go back before we ever had a constitution, go back before we ever had a government, and everyone would govern themselves. But you have to have laws. If you have laws, they have to be abided by. If they are not abided by, you have to have someone to enforce them. Our society requires it.

I sense that’s been a very rewarding life for you.

Frank Johnson: I feel that I’ve had a very rewarding career.

It’s kind of a unique job, isn’t it, being a federal judge? A uniquely responsible position, too.

Frank Johnson: That’s right. There are not many federal judges. You can’t let the position give you the idea that you can’t make mistakes, or you can’t do anything wrong. You still have to be sensitive to what you are doing, and make certain that you do right. It puts you under a lot of pressure, because a lot of people are looking at you just to make sure you do right. They want to criticize you. So you try to do the best thing you can, do what’s right.

People talk about stress in their lives. “What a stressful job!” How do you deal with that stress? That pressure on your shoulders?

Frank Johnson: Doesn’t bother me. I don’t know of any job that doesn’t have stress.

Looking back, is there anything you would change about your career?

Frank Johnson: Oh, my goodness, yes. You’d have to give me two weeks to think of the answer for that. You can’t look back. You have to do what you think is right. You have to do it in the best manner you can, and then you don’t look back. If you do, you would be under a lot of stress.

We want to thank you for your service, and for speaking with us today.

I’ve enjoyed talking with you. Nice interview.