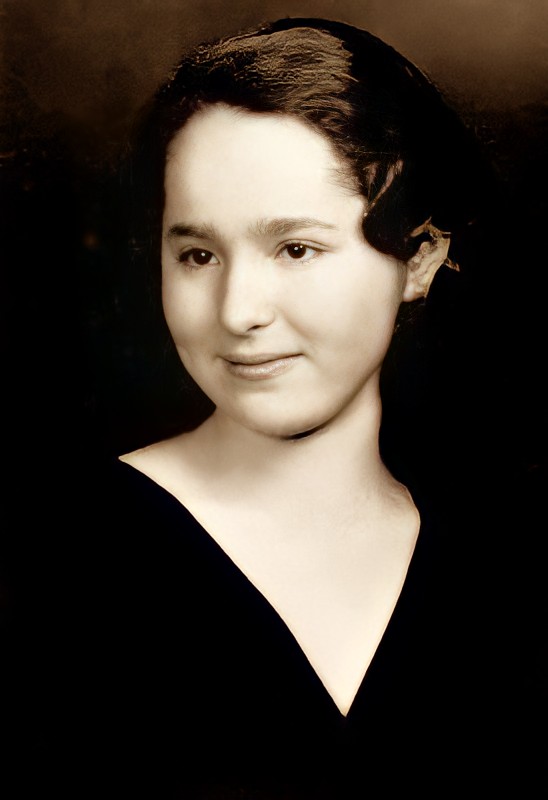

Some of us imagine a scientist comes from a long line of scientists. That doesn’t seem to be true in your case. Were there any scientists in your family?

Gertrude Elion: Not that I know of. My father was a dentist. I have a brother who is also a scientist, a physicist and engineer. My father wanted both of us to be dentists, but we couldn’t see it. My brother’s children have a scientific bent. One is a cardiologist, one’s an engineer. Maybe we passed on some of it to other children in the family, but we certainly didn’t come from a scientific family.

When you were growing up, were there any people who particularly inspired you?

Gertrude Elion: I can’t remember that anyone in particular did. I think perhaps it was my mother who influenced me the most. She was a housewife. She had no higher education, but had the most common sense of anyone I knew, and she wanted me to have a career. So she was always very supportive, at a time when many women of her generation would not have been.

How do you account for her forward-looking attitude?

Gertrude Elion: I think she herself probably felt deprived that she had never been able to do anything more. She married very young, 19. She had a child when she was a little over 20, and from then on her career was in the house, as most women’s careers were.

It sounds like your mother, though she was not a scientist, had a great influence on you. How is that?

Gertrude Elion: Partly because she believed that I could have a career. When I was discouraged, she always said, “Don’t let that upset you. You know, you can do it. She also was a self-taught person. She read prodigiously. She didn’t have anything beyond a high school education, but all through my years in high school and college, when I brought home books in literature, she would read every one of the books that I read. She didn’t read the scientific literature, but she understood what I would tell her in terms of what I was doing.

I would always bring home work on weekends. And in the country — we had a cabin not far from New York, and I would come, and I would sit under the apple tree and write papers. And my mother would always say, “Does your boss know what you do on the weekends?” And I would say, “I’m not doing it for him, I’m doing it for me.” And one weekend, I came without any work, and she said, “You are not feeling well. And I said, “I’m feeling perfectly — “ “Oh, no! You are not telling me the truth. If you were feeling well, you would have brought some work with you.” So she had gotten used to the fact that I was supposed to work, that if I didn’t, it was obvious that I was sick.

You were lucky to have such a mother.

Gertrude Elion: Indeed I was.

Were you inspired by any scientists you read about?

Gertrude Elion: I read about Madam Curie of course. That said to me that a woman can do it, too. There was also a book called Microbe Hunters by Paul DeKruif, which dealt with a lot of very exciting discoveries by people in chemistry, physics, biology. It’s a book that’s overlooked these days which I think all children should have to read. It dealt with people like Jenner, and the smallpox vaccine. These were biographical sketches, not just about their discoveries, but about their lives. Paul Ehrlich, Louis Pasteur, and what wonderful things they were able to accomplish from very poor surroundings. Each one had an entirely exciting life, a lot of struggle but a lot of satisfaction, a lot of achievement.

That book gave me the feeling that it was all right to struggle, it was all right for it to be hard. It didn’t have to come easily, and yet there were so many things to be done in science. I think I read it in high school, but I would like to give that book to every child in the elementary schools, not just in high school, actually.

How about Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis?

Gertrude Elion: Oh yes. It was a book where real people had real struggles. They accomplished amazing things, even though they didn’t know what they were going to accomplish when they started out. I think that people need a goal, but I don’t think they have to feel that goal is immovable. They might find a better goal along the way.

Isn’t there a passage in that book where somebody dies, and a person is thus inspired to search for a cure?

Gertrude Elion: No, actually the person is searching for a cure, but then his wife dies of the same disease. He was already on the track, but it just pushed him a little harder.

You must have related to that.

Gertrude Elion: Oh, yes.

When you got to school, was there a teacher who inspired you?

Gertrude Elion: I liked many of my teachers, but not particularly the science teachers. I went to an all girls school and I had a feeling that the people who taught science didn’t think we were really taking this very seriously. They thought we were just taking science because it was another course. Maybe that’s the reason I didn’t relate to them. I related more to my French teacher, for example, who was very good, and who taught French beautifully. I became very friendly with her, but on the whole I found teachers to be very stand-offish. Of course, I went to a very large school, not a small college where students and faculty mix much more. That probably accounts for it.

After you got out of school, you struggled to find work in your field. Did you ever sense that there was a brick wall there that you weren’t going to pass through?

Gertrude Elion: I did. I think I sensed it about three or four months after graduation. I said, “Well, I’m going to have to earn a living. I guess I’d better go to secretarial school.” And so I started secretarial school. And I worked. I went for six weeks. And just at that point someone offered me a job as a lab assistant in a school of nursing for three months. It was a trimester. So I dropped secretarial school and took this three month job, and then I was out of a job again. But once I tried secretarial school, I knew that I couldn’t — I wouldn’t — ever stay there. It was only six weeks, which was about as much as I could take.

What did they pay you for this lab work?

Gertrude Elion: They paid me $200 for the three months. I remember the amount because when I went to the bank to cash my check, which was for $66.66 each month, they all thought it was very funny.

That must have been hard to live on.

Gertrude Elion: Yes. I was living at home. That was essentially just carfares and lunches.

Didn’t you also do a stint teaching?

Gertrude Elion: Oh, yes. After this three-month job, I was again out of a job, and I ran into someone at a party — a chemist who had a lab. He worked by himself in a factory building. I asked if I could come and work for him, and he said yes, but he couldn’t pay me. I said, “That’s all right, I still need the experience.” So I went to work for him. He was a very good organic chemist. I worked for him for a year and a half. At the end of that time, he was paying me $20 a week. From that, I saved enough to go to graduate school at NYU. I went there for a year and finished my master’s degree. There were still no jobs, so I taught high school chemistry and physics for two years.

Then the war came, and all of a sudden there were jobs and nobody to fill them. So I left teaching at the end of two years, and began to work again in a laboratory, only this time not in research but doing food analysis for the A&P grocery chain. You know, measuring interesting things like the acidity of pickles and the color of mayonnaise. But it was a good experience because I learned a lot of instrumentation, so I stayed there for a year and a half.

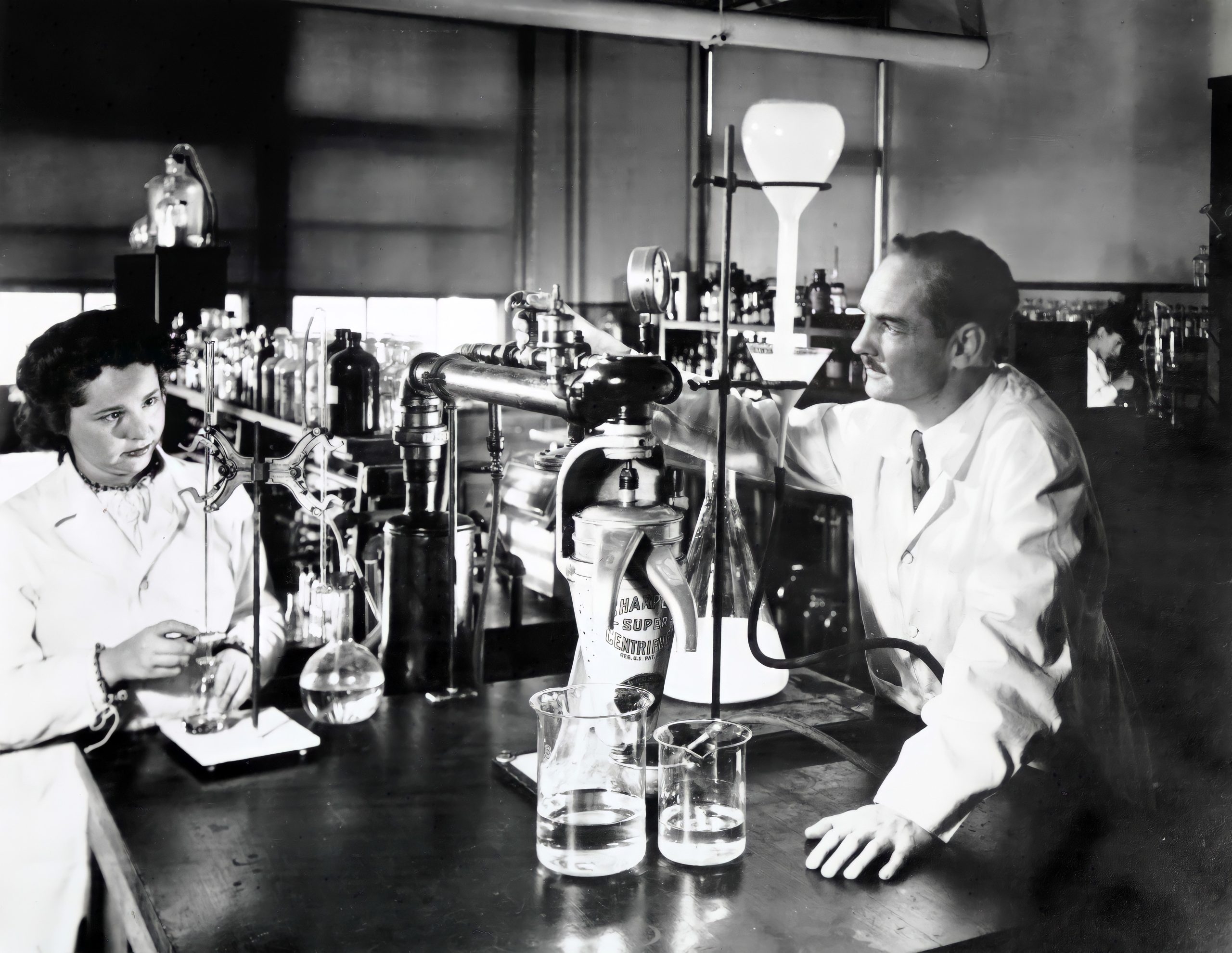

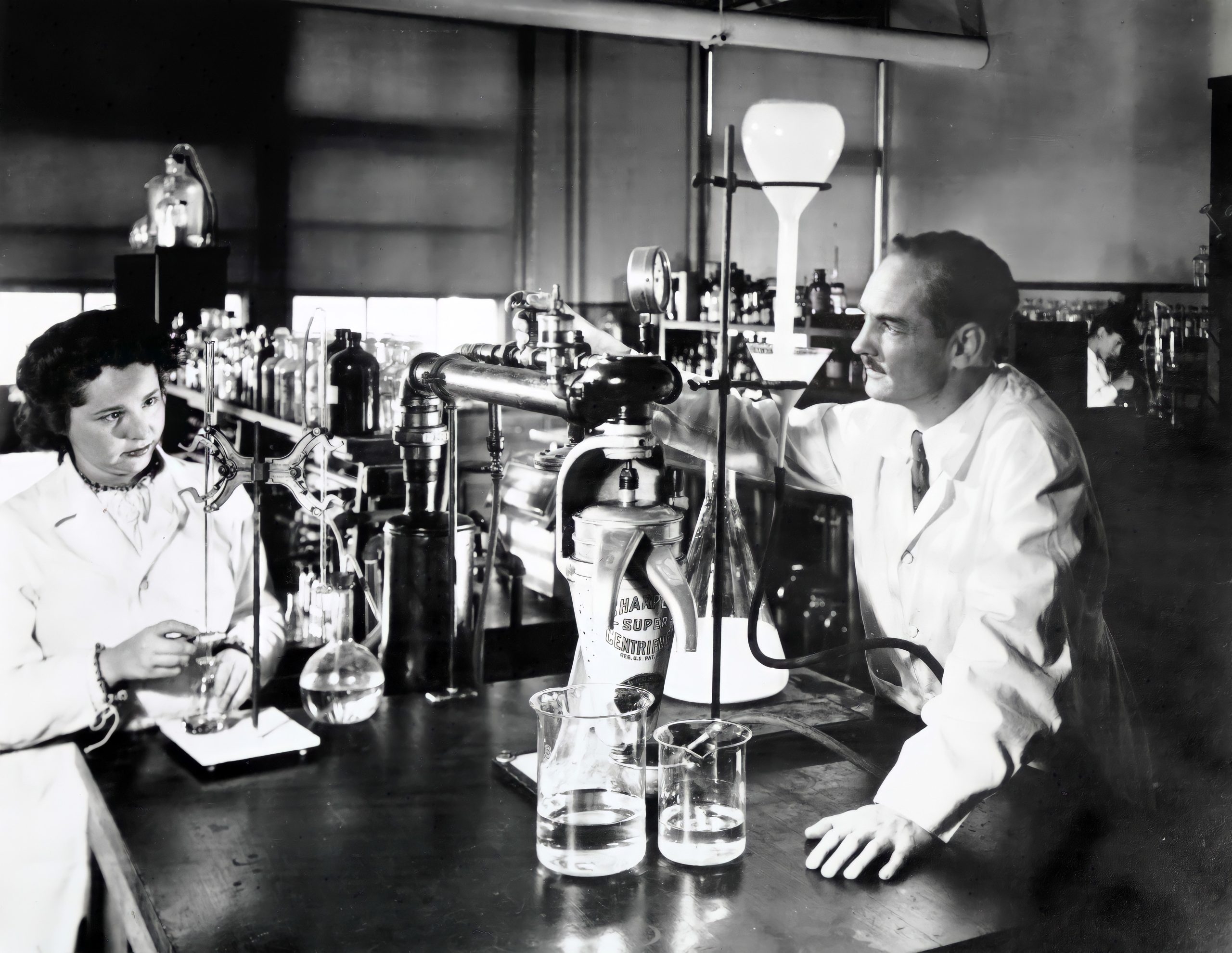

Then it was time, I thought, to find me a research job. And I one. I’m not really sure how I got it, but I applied for a job at a new Johnson & Johnson laboratory in New Brunswick, New Jersey. They had decided they were going into the pharmaceutical industry. The man who was hired to head this was a chemist from American Cyanamide, I think. He was allowed to hire two assistants, and I was one of these assistants. Six months later they changed vice presidents, and they said, “No, we decided not to go into the pharmaceutical industry.” So I said, “Does that mean I’m fired?” And they said, “No, we won’t fire you, but we’ll give you a different job. We’ll let you measure the tensile strength of sutures. You hang weights on the ends of these strings, and you see at what weight they break.” And I said, “No, I don’t think I want to do that.” So I left, and that was when I went to Burroughs-Welcome. That was 1944.

Was it very daring for Dr. Hitchings to keep you on and promote you without a doctorate?

Gertrude Elion: It was very daring. I never questioned him about it. I think he thought there was a certain gleam and a certain intensity in my work. It would take me a little longer perhaps, without a Ph.D., but he was prepared to give me the opportunity. That’s what made the difference. Not everyone would have done that.

If you had it all to do over again, would you still follow the same path?

Gertrude Elion: I think under those circumstances, I would follow the same path. It isn’t the path that I would tell other people to follow. I think it’s much easier if you get your Ph.D. first. It just was the wrong time for me to drop my job, and it had been too difficult to find the right kind of job. In a few years, I realized that I had made the right decision, because we began to find compounds active in leukemia, and the excitement of the work was such that it couldn’t possibly have happened, I think, in another laboratory. Maybe in a much larger laboratory. So I was in the right place at the right time.

Did you sense that you were accepted as a woman right away at Burroughs-Wellcome? You’ve said Dr. Hitchings was open-minded, but were there other people who resented you?

Gertrude Elion: I didn’t find anyone who resented me, but I don’t know that I would have noticed. There was so much to learn, and I was so focused on learning. It was a new field for me, actually. What he was doing was new for its time, as well as for me, so there was a great deal to learn, a lot of reading to do. I had a lot of encouragement from him, so I’d never stop to think whether anybody resented me or not.

The Nobel Prize rewarded not only your invention of specific drugs, but the way that you revolutionized the way that drugs are developed, in general. When did it occur to you that you could design drugs, rather than follow the traditional trial-and-error approach?

Gertrude Elion: I don’t think I can take credit for that. It started out in almost a naive way. I was only following what Dr. Hitchings had decided was the way to go. He didn’t know any more than I did whether it was going to succeed at the time. We knew something about the nucleic acids which make up the nucleus of the cell. We knew it was very important for cells to have this in order to divide. We didn’t know much about the structure — it was prior to the Watson hypothesis of the double helix — but we did know that there were four bases that were essential for nucleic acid. So the thought was, “What would happen if we made artificial bases? Things that look very close to the regular ones, but couldn’t really be utilized by the cells.” That was the approach. We didn’t understand all the pathways, how these compounds could be used, or what would happen if they got into the nucleic acid. So, the idea was not that we knew exactly what to make, only that we would make things so close to the original that it would fool some enzymes, some cells into taking them up. We used to call it a rubber donut. It looked like the real thing, but it wouldn’t work, and that’s what we found.

Then we had to find specifically in what kinds of cells these compounds would work. Some of them worked in bacteria, some of them worked in malaria, some of them worked in cancer cells, some of them worked in viruses. It wasn’t predictable in the beginning, so we looked as widely as we could. As soon as we got a lead, we could make compounds similar to that, find the best one, and so on. In a sense it was trial and error, but something Dr. Hitchings used to call “enlightened empiricism.” In other words, you knew the kind of thing you were looking for, and you were making that kind of compound, but you couldn’t predict which one would work for what. In a sense, I think of it now as invention of new compounds and then discovering what they were good for, because it wasn’t really a single process. We didn’t know ahead of time which one would work for what. Perhaps that’s why we went into so many fields.

Can you explain, in layperson’s terms, how that approach differed from the traditional approach?

Gertrude Elion: The traditional approach was to take something that worked and to make some changes in it, and see if you could get another compound that worked as well. Or to take things off the shelf and try them. Things that had never been looked at before, even natural products, or just chemicals. Well, we didn’t do that. I mean, we made specific kinds of chemicals with very specific ideas in mind.

We had a bacteria in the laboratory that we used to say was our little black box, because it knew how to grow with very simple bases that were nucleic acids. If we gave that bacterium the wrong compound, it didn’t grow. So the bacteria knows that it’s close but not the right thing. Then you have a lead to follow. You might have put in a sulfur instead of an oxygen. That’s what we did with a very simple base that turned out to be an anti-leukemic drug. The bacterium, which is a milk bacterium, Lactobacillus casei, knew that compound wasn’t the right one. It tried to use it, and then it was inhibited, it couldn’t grow. So we said, “OK, that will inhibit growth. Let’s try a mouse tumor. Let’s see if that will be inhibited.” And sure enough, it was. “Well, how about a mouse leukemia?” Yes, it inhibited that. “Well, how about a human leukemia?” So, it was a step-wise thing from a simple organism that recognized that this was not the right base, to go on from there.

What people in general were doing in pharmaceutical companies was saying, “I want to develop a diuretic. I’m going to test everyone of these compounds as a diuretic.” Even though you don’t know what the mechanism is. We learned a lot about biochemistry with these compounds. We learned some of the pathways that existed but which we hadn’t clearly identified before. So the compounds themselves ended up being tools for discovery as well as ends in themselves. One of the most important things about discovering new drugs is to let the drug lead you to the answer that nature is trying to hide from you. We were able to deduce that certain enzymes existed, even if we didn’t have a name for them. Then these enzymes were discovered, and it was this wonderful feeling of “There it is!” We knew it was there, now it has a name.

It sounds to me like your approach was to respect and to analyze the bacteria itself, rather than just throw things at it blindly.

Gertrude Elion: That’s right. We could say, “OK, the bacteria is inhibited. Why? Let’s give it the natural base that it needs. Will that reverse the inhibition? And the answer was yes, it would. Therefore, those two are on the same pathway, and we have hit the pathway we are looking for.” You could organize your tests in such a way that you could actually determine what would reverse the inhibition, and that would give you a clue as to where it was working. This is what made it so exciting. There was so much to learn. In the 1950s, when all these things began to come together — we learned how the nucleic acids are synthesized, what the structure looks like, what the enzymes were — we already had all these things to plug into it. We had known that they existed, but we didn’t know what to call them.

Did you have any inkling of the far-reaching effects of these ideas in the medical world?

Gertrude Elion: Not until they happened. Many of them happened maybe because the time was right, the instrumentation changed, we could determine things we couldn’t have determined in the 1940s. We were able to do things much faster because of mechanization of spectrophotometers, radioactive precursors, being able to have scintillation counters. The revolution in instrumentation that happened after the war was so phenomenal. Looking back on it now, I realize experiments that took five years could have been done in five days.

It sounds like a scientist has to be able to get along well with colleagues and have a spirit of team playing. Otherwise you are stuck in your own laboratory with no input.

Gertrude Elion: Absolutely. I think that there is no question in my mind that it is a team effort. It’s a team in the beginning, and it’s a team effort all the way through. There are so many aspects of drug development, finding out what are the side effects are, finding out the best way to give it, finding out any number of things. One person can’t do that. You could, I suppose, if you spent a lifetime on every drug. I’ve always compared it, in a way, to an orchestra. Everybody plays his own instrument very well, but it isn’t until you put them all together that you have anything that sounds like music.

It also sounds like you have to be brave enough to spread the word about what you are doing, and not be too possessive of it.

Gertrude Elion: That’s true. I think we publish very widely. There are short periods where you can’t do that, especially working in a pharmaceutical company, where you have to protect your work with patents for the sake of the company. You have to keep it under wraps for a year or two, particularly if you know you have something very novel and very hot. Then you know that other companies, with three times the staff, will jump into the field almost immediately. That happened to us with the antiviral drug, acyclovir. Nobody was working on antivirals until the first big success, and then everybody was working on antivirals. As soon as we had the patents not just filed but issued, we began to publish prolifically. I’ve had over 200 publications, so I know how much we’ve published.

What was the influence on your work of the findings of James Watson?

Gertrude Elion: It was a very important finding for us because we were involved in nucleic acids. There weren’t many people interested in nucleic acids. There weren’t many people who believed that was the way to find drugs. But when we found out the structure, and we began to understand what kind of bases could be incorporated, and which ones couldn’t, and where they could be incorporated, it put a whole new dimension on it. So it had a very significant effect. Up until then, we weren’t quite sure what the effect of incorporating an abnormal base would be. We didn’t know there was such a thing as a double helix. We didn’t appreciate that we could get something in there that could distort that helix and make it non-functional. It was a wonderful piece of discovery for us, right at the most appropriate time.

So, in a sense, it speeded things along.

Gertrude Elion: Oh, yes. And again, it explained a lot of unknowns. It explained things, it gave us clues on which way to turn and what kinds of compounds to make next.

Were colleagues of yours in the field skeptical at the new approach that you and Dr. Hitchings were taking?

Gertrude Elion: Yes, I think they were. They thought we were just playing. When the first successful drug came, people sort of raised their eyebrows, and said, “Wait a minute, maybe there is something to this.” Of course, it also came at the right time. It came in the early ‘50s, when a lot of these enzymes were being discovered. The double helix was in ‘53. They got the Nobel Prize for it, so the timing was perfect. Everybody began to think maybe this is the way to go. From a time when everyone interested in nucleic acids could probably sit around one table in a lunch room, it got to the point where a conference on nucleic acids was oversubscribed, and you couldn’t let everybody come who wanted to come.

Were you affected by other people’s skepticism?

Gertrude Elion: Not really. My feeling was “Maybe you are right, maybe we are right, we’ll see.”

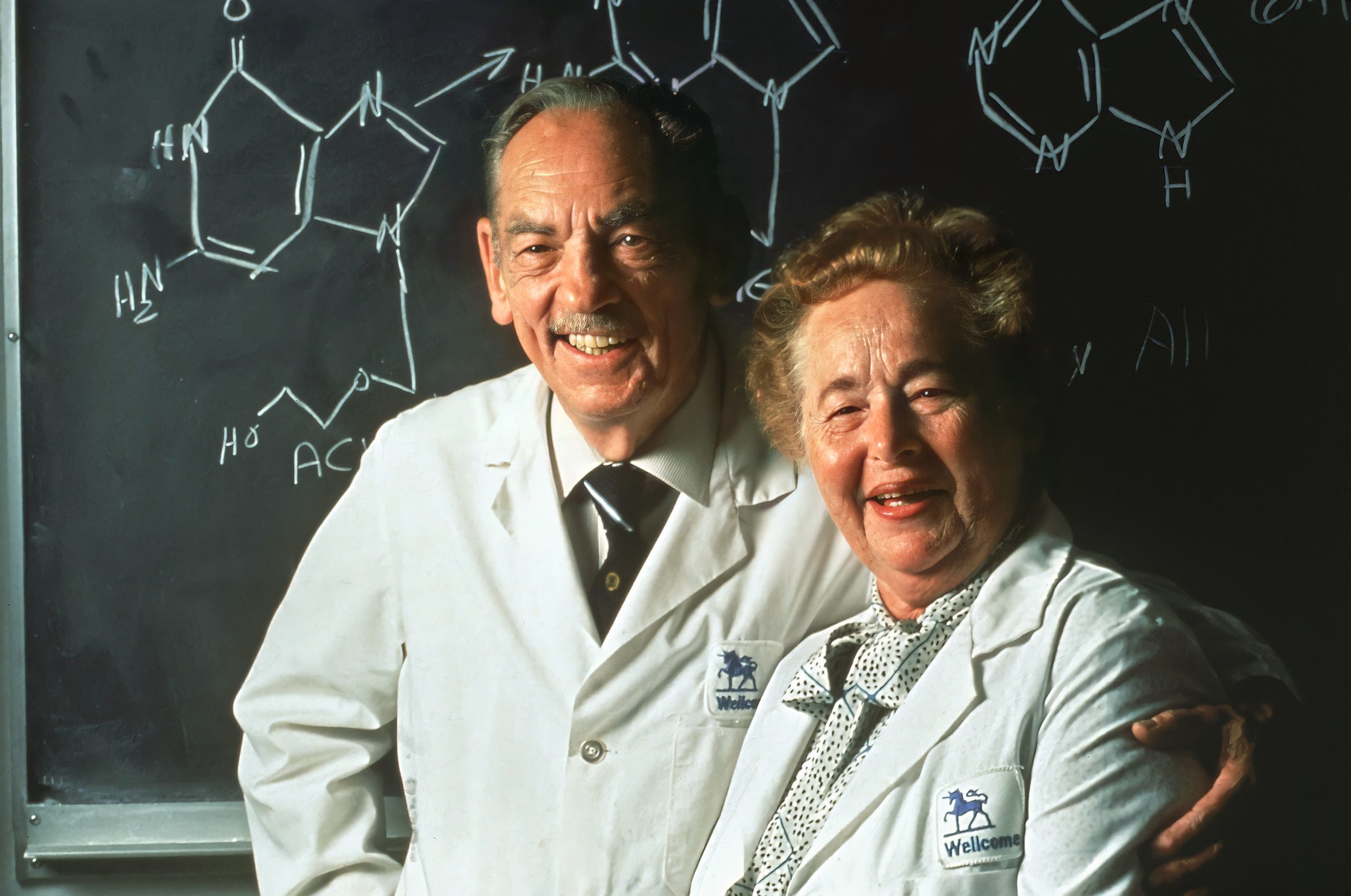

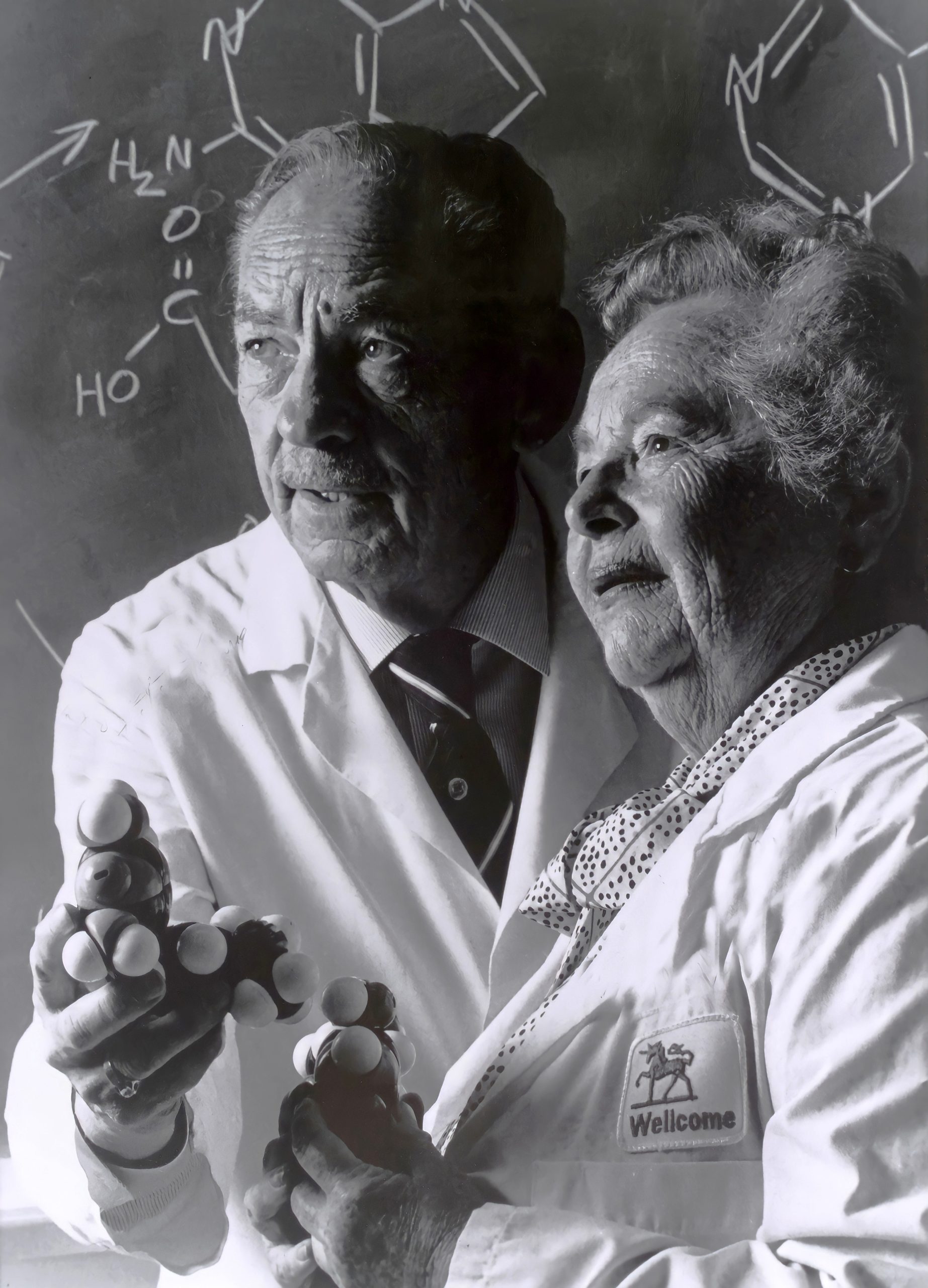

This partnership that you had for many decades is quite an extraordinary one. How did you and Dr. Hitchings complement each other? Was it immediate?

Gertrude Elion: No, I don’t think it was immediate. It was a boss/assistant relationship for the first couple of years. He is always willing to let people do the maximum that they are capable of doing. That’s not true with a lot of people. I would read a lot, I would question why, I would have my own ideas, and he would encourage me to do that. Little by little, I began to have my own thoughts about what to make, and I began to get assistants to help me. I was working in the purines, someone else was working in the pyrimidines, and gradually these two began to branch out into different diseases. I was following one line, someone else was following another, and Dr. Hitchings was the overall coordinator. Each branch got bigger and took on more and more people. Suddenly had a department of 20, and 25, and 50, all responsible to me. It just happened gradually, as the need arose. “He never said, “OK, you’ve gone as far as you can go.” That’s why I stayed, and that’s why I prospered. I felt it was up to me to do the best I could, and not to be hampered in any way, to be encouraged along the way.

Some people are threatened by a young upstart.

Gertrude Elion: That’s correct. He was very unusual.

Obviously, this grew into more of a partnership.

Gertrude Elion: As time went on, he became more and more the administrator and the coordinator, and we were the soldiers in the field doing the actual work, the actual synthetic, biochemical work, and reporting to him. I think I had a little more patience to do the nitty-gritty kinds of things in the laboratory, but he had more insight, more appreciation of what these things all meant. We would have long talks about it. At the end of a long talk, you wouldn’t really remember who said what and whose idea it was to do the next thing, which was great. You could never say, “You told me to do this,” or “I was the one who thought of it.” It was very much a meeting of the minds.

That’s quite admirable for that period, for a man to treat a woman as an equal.

Gertrude Elion: Yes, it is.

Could you tell us how you figured out the difference between normal cells, cancer cells and bacteria?

Gertrude Elion: It was experimental testing. What you had to do once you found a lead compound was to put it into a whole animal and say, “OK, this tumor is not growing. What about the animal’s bone marrow? What about the animal’s intestinal mucosa?” These are natural, normal tissues that divide rapidly. So if you’re only hitting a rapidly dividing tissue, you may end up with toxicity. You can’t determine the toxicity ahead of time, until you begin to compare what it does on the tumor versus what it does on the rest of the animal. You find, in cancer therapy mainly, that there isn’t a large difference. In other words, you will eventually reach a level which will be toxic to the host. You’re sort of walking on a tightrope, trying to find out just how much is necessary before you run into toxicity, or you try to find a compound that may have a better therapeutic index.

It’s not as true in antivirals, because the virus metabolism is very different from the host. It was possible to get big differences between the normal cell and the affected cell. You could find things that were very safe, that really inhibited bacteria, because they have a different metabolic route for getting there. You could do that with malaria. The malaria parasite has a different mechanism of making its nucleic acid from the normal, but until you tested it in an animal, you really couldn’t be sure. I’m not very patient with animal rights activists these days, because they seem to think that you can predict toxicity on a computer, but you don’t have a liver in a computer, or a kidney, or bone marrow. Until you have it tested in an animal, you really don’t know what you have.

As I understand you, this is why people have strong reactions to chemotherapy. This stuff does affect normal cells.

Gertrude Elion: It does. Most of the anti-cancer drugs we have today are really not that selective. That’s been their problem. Nowadays, I think, we are beginning to understand a little bit more about the cancer cell. What is different about it? Maybe we will eventually have compounds that will be more specific and more selective. The outlook is really good in that direction, but it may take a long time.

It seems that you and Dr. Hitchings were going in a completely new direction with your research. How were you looked upon in the field?

Gertrude Elion: The field was new. People hadn’t thought of anti-metabolites, which is the name it finally got. Except for two people, Woods and Fildes, who had postulated that the reason sulfonamides affected bacteria was that these sulfonamides look very much like a natural nutrient that bacteria needed. This interfered with their getting it, and it was structurally quite similar, and people were willing to believe that was possible. But then Dr. Hitchings said, “If it happens with one nutrient, why not with nucleic acid derivatives?” In his doctorate he had worked on the purine and pyrimidine bases. “Why don’t we try this anti-metabolite approach to the nucleic acids?” People thought that was a real wild dream. “Just because you work with sulfonamides and bacteria, now you are talking about the structure of a living cell. Obviously, you are not going to find something that will work on one kind of cell and not on others. So all you are going to end up is making a lot of poisons.” So we were off in our little ivory tower and nobody bothered us, and nobody paid much attention. It took the first active compound for people to say, “Maybe that’s not such a stupid idea after all.”

People were still skeptical until it showed activity in man. You could report that these worked in bacteria, and nobody paid much attention to that, because often the bacteria weren’t even the real pathogenic bacteria that cause disease. It was just a bacteria that grew in milk, and who cares if you can inhibit that? I don’t think we really cared whether they believed us or not. We knew it was working, and we knew we were on the right track. It got to be almost a joke in the lab. “Now we have all the cures, we have to find the right diseases for them!” We were obviously interfering with nucleic acid in some of these. The anti-malarial compound and the pyrimidine series came at just about the same time as the anti-leukemic drug in the purine series. So we had both arms showing activity in two entirely different types. Then people began to say… “ Here’s two different kinds of drugs coming out of this work. Maybe it’s not so silly after all.” That was nice, although it made for more competition of course.

And then people jumped on the bandwagon?

Gertrude Elion: They jumped very quickly on the bandwagon. It was obvious that there were a lot of changes that could be made that we hadn’t tried yet. We just kept plugging away. We knew that we didn’t have enough chemists to compete with Merck, or Ciba-Geigy. So we just went on with our business as best we could. I didn’t worry about it.

What was the general philosophy at Burroughs-Wellcome? What were they trying to do as a company?

Gertrude Elion: Burroughs-Wellcome is a very unusual company. It was founded as a foundation, and all of the money that was made by the company went to the foundation and then to the trust that distributed it in philanthropy. So there were no stockholders. It was the vision of Henry Wellcome that this would be a research organization, and it would make its money by selling pharmaceuticals, and that money would go back into research. Our research lab grew very rapidly as we began to be successful. The money did go back to research. Some of it went to our research, some of it went to other people’s research, via the Wellcome Trust. It’s a little different now, because the trust has sold a quarter of the stock into the open market and there are stockholders, but the trust still owns 75 percent of it, and the mission is still to have new drugs, not repetitions of things that are already in existence, but to open new fields. That was what we tried to do. We weren’t trying to imitate anybody. We weren’t trying to make another diuretic, another analgesic, things that are already doing pretty well. Not to say that we don’t have such drugs, we do: over-the-counter antihistamines and things of that sort. But on the whole, the idea was to do research, find new avenues to conquer, new mountains to climb, and very supportive of research.

It’s extraordinary that you stayed at the same company all these years. You obviously found a comfortable home.

Gertrude Elion: I wouldn’t say it was comfortable, but it was challenging. It was a place where you could do good work. People wouldn’t be looking over your shoulder saying, “What have you done for me lately?” For example, we ended up in the field of gout, which nobody had any intention of getting into, until we discovered that one of the ways that 6-mecaptopurine was destroyed was through an enzyme in the body that oxidized it. We set out to prevent the oxidation. We did, and we ended up with a compound that prevented the formation of uric acid. That became a very big item for the company because there were many people with gout, and it was very good treatment. As long as we continued to come up with novel things, nobody said, “Why haven’t you done this, or why haven’t you made that?” Which is a very enlightened research management. Considering the size of the company, which was much smaller than most of the big ones, we probably wouldn’t have done as well if we hadn’t been allowed to go into new fields.

You repaid them by being very faithful.

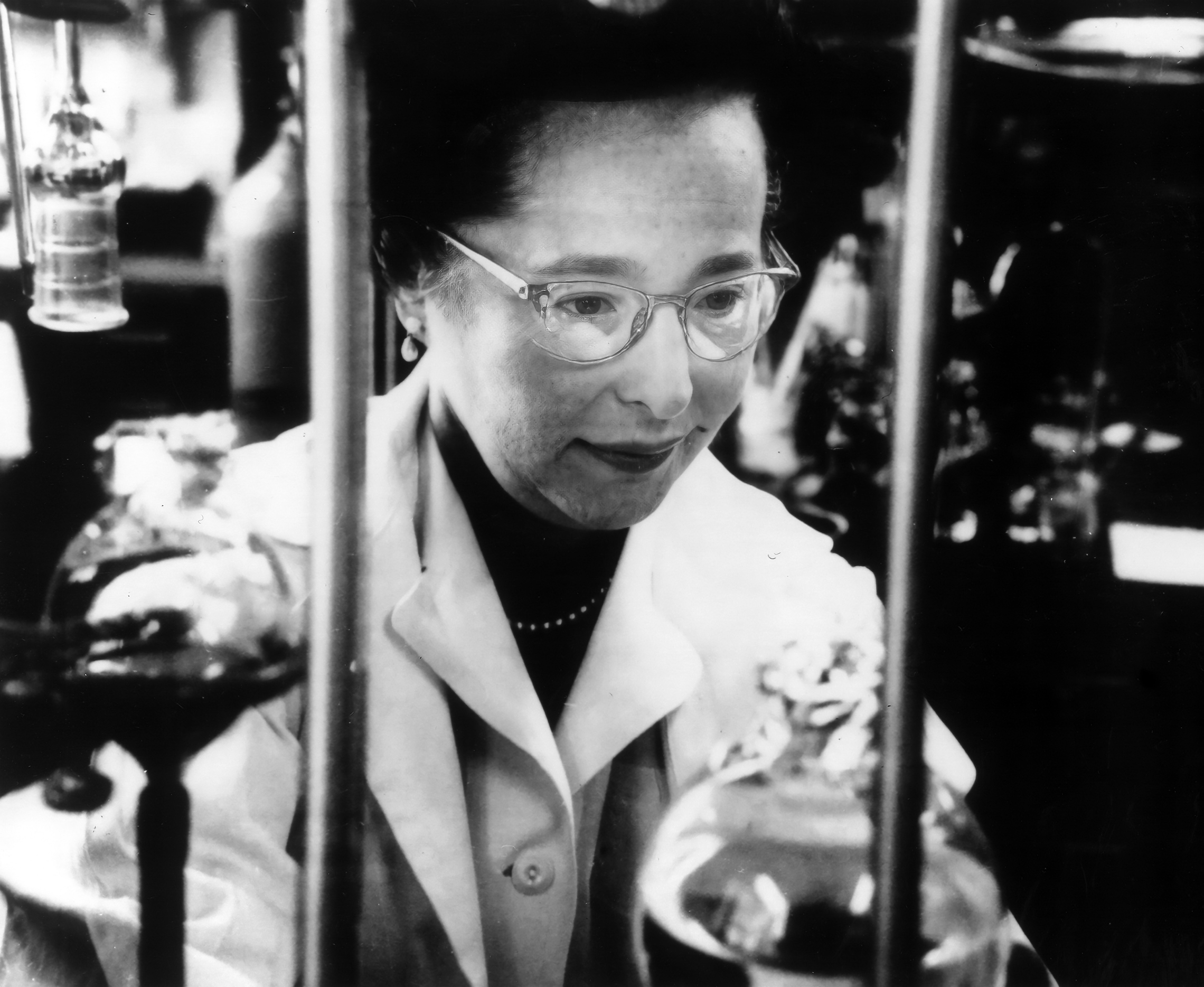

Gertrude Elion: I originally set out thinking, “I’m going to stay here as long as I continue to learn.” Here I am, 46 years later and I’m still learning.

I wanted to focus on your revolutionary development of acyclovir, which has been called your crowning achievement. What was so dramatic about this discovery?

Gertrude Elion: Antivirals up until the late ‘60s, beginning of the ‘70s, really were considered to be a kind of field that drug companies didn’t get into. Because viruses are nucleic acids, that’s what they are. And therefore, a few compounds had been found that inhibited the growth of viruses, and they were inevitably toxic to the cells. And it became the philosophy that had to be that way. If it was going to hit the nucleic acid directly, the virus couldn’t modify this compound, and it was a no-no, stay away from viruses.

Then in the late ‘60s, a compound that had some antiviral activity was isolated from a natural product. I think it was from a sponge. It was toxic to normal cells but the therapeutic index was a little bit better than what had been found before. It was a purine, and I had been working all my life on purines. People hadn’t been working with purines as antivirals. They had been looking at pyrimidines and those were pretty toxic. Why not go back and see if some of our purines aren’t antiviral? It had an unnatural sugar on it. So we began to make these modified sugars, and we found things that were just as good, or better, than this thing that was found in a sponge. They still weren’t a large therapeutic index, but they were manageable.

In the meantime, Dr. Schaeffer came to work for us in 1970. He had been playing around with the sugar molecule on these bases. Instead of the whole ring system, he’d made just a piece of the sugar. He saw that you don’t need the entire sugar to bind to the enzyme he was working with. The enzyme will recognize even this one piece. That sounded like a good idea to exploit, so we put his false sugar on the purines we were working with. We tested it on herpes virus and, lo and behold, this compound had high activity. Amazingly, they were very non-toxic. We didn’t even have the virus growing in our laboratory, so we would send these compounds over to our laboratory in England, and every time something was really active, we’d get back a telegram with the results. We were in a state of absolute frenzy, because these things were so much more active than we had expected, and so much less toxic.

And that became the question mark. Why is that the case? We put all our efforts into finding out what was going on in a virus-infected cell. Then we began to find that these non-toxic compounds were actually being activated by the virus itself. The virus was converting it to the toxic compound. It took three steps to get to the really active antiviral compound before it inhibited the polymerase that the virus needed to make another copy.

The revolution came partly from having made the compound, but even more from having shown why it was so active and so non-toxic. It was just a big explosion after that. Now people look at all the viruses to see what specific enzymes they have. It’s true with HIV, its true for the Epstein-Barr virus. There are so many viruses, and they each have different enzymes. Even herpes type I and II are different. It turns out they are very close as far as acyclovir is concerned, but not so far as all the other compounds were.

Do you remember a particular afternoon when you got the high active results?

Gertrude Elion: In order to find out what was different about the drug in a virus-infected cell compared with a normal cell, we made a compound with radioactive carbon in it. We incubated the compound with the virus-infected cell for seven hours, and did the same to normal cells in which the virus would ordinarily be found. We made an extract of these cells, put it on a high pressure liquid chromatographic column, which would separate out the various components in the extract. And there, lo and behold, were four radioactive peaks in the virus-infected cell, and only one in the uninfected cell. That was the day when you knew where to look. And something was happening that was really specified by the virus.

How did you feel?

Gertrude Elion: We felt it couldn’t be true. Everybody was very excited. I had the most wonderful group of young people working together on this. If ever there was a team effort, that was the one. Everybody in the lab would come and say, “What can we do? What part of the action can we have? “ It was really tremendous.

What was the time frame between that day and acyclovir being sold in the drug stores as Zovirax?

Gertrude Elion: It was only about eight years, which is very short for a drug these days.

Did you realize the far-reaching implications of that discovery?

Gertrude Elion: Probably not. We were too busy. The fact that it had an activity was known in ‘73, the discovery of the mechanism, was in about ‘74. The fact of why it had the activity took maybe six months to a year. But… Well, I think we realized the far-reaching consequences for that compound, but I don’t think we appreciated immediately for a lot of other viruses.

What was the connection between your research with viruses and the first successful treatment of AIDS?

Gertrude Elion: I retired as department head in ‘83. I think the first successful treatment against AIDS came along about two years later. The same group of people that had worked on acyclovir worked on the AIDS drugs. Viral research was now a major effort for the company. At that particular time, we didn’t even have the AIDS virus in the laboratory. We had to build a special lab, because it’s such a dangerous virus to work with. But we had continued to make of the same sort of compounds these with strange sugars. We tested it on a number of viruses and we sent it out to NIH (National Institute of Health). We said, “Would you test compound S and compound T on the AIDS virus?” without telling them what they were. Lo and behold, this one was very active. From the time that activity was discovered to the time we really had an AIDS drug was very short, about two years. It was done by people that were trained to do viral research, and they did the right things. But I don’t think I should get credit for anything to do with the AIDS drug.

Except that they couldn’t have done it without your research.

Gertrude Elion: That’s true, but they knew what to look for, and they know how to look. All science is a continuation of science that went before.

In your field there’s one great stumbling block, and that’s curing viruses. Any hope in that direction?

Gertrude Elion: There are some viruses, probably, that one can cure. But mostly, if you think about viral diseases, the big success has been with vaccination. It was true with polio, it was true with smallpox, it was true of measles. When you can get a good vaccine, and prevent the disease, that’s the best thing to do. The next best thing is to prevent the virus from becoming latent. The reason it’s so hard to cure virus diseases is that you may stop it from multiplying, but it doesn’t necessarily go away. It stays dormant in some cell types, depending on the virus, and comes back. The patient gets elderly, or sick from some other disease, or the patient gets into an emotional state, and suddenly this virus reappears. It’s true with the AIDS virus. It actually integrates into the normal DNA of the cell. Until it comes out and tries to reproduce itself, it just sits there, and there is not much you can do about it. So if you could prevent it from getting there, if you could prevent it from integrating, if you could kill off every cell in which it was integrated, maybe you could cure it.

Is that possible?

Gertrude Elion: Nothing is impossible.

Do you feel that luck has had a role in your career?

Gertrude Elion: Luck has a role in everybody’s career. You can find a dozen times when it could have gone either way. That interview could have been the other Saturday, and someone else would have interviewed me. I think about it often, how a particular person who wrote to me and asked for a compound, and made a discovery with it, which changed the whole line of what we were doing. You can’t do it without luck, I’m sure, but I think you have to recognize the luck when you see it.

And be prepared to change directions?

Gertrude Elion: Yes, absolutely. We changed many times. We got into fields that I never expected to be in originally. I thought cancer was what I was going to do, and it is what I did for the first ten years. But then it changed to other things.

I’m struck by the drive and the sense of confidence that is apparent in the whole path of your career. Did you have fears of failure?

Gertrude Elion: Not really. I had fears that a particular experiment wouldn’t work, or maybe a drug I thought was going to work would not. That happened, of course, all along the way. It has to happen in a long career. What you have to gird yourself to do is to say, “OK, that one failed. It was a step which was in the wrong direction, so let’s go back to the crossroads, and go in a different direction and not let the failure be the end of the line.” I did learn how to do that. “OK, now I know that doesn’t work. I don’t have to do that again, I can head this way. Somewhere there is an answer. It may take five years, maybe ten.”

I think you have to have infinite patience to be a scientist. I used not to realize that, because I remember telling someone once that I didn’t want to be a teacher because I didn’t have the patience. And they laughed, and said, so you want to be a scientist. And I said yes. I didn’t even think it was funny at the time. I now think that it was very funny. You have to have the patience. That’s what I always tried to instill in the people in my lab, that they shouldn’t be too discouraged if something didn’t work, that it wasn’t the end of the line.

Describe your alleged retirement schedule.

Gertrude Elion: I am a consultant at Burroughs-Wellcome. I have an office which I go to every day that I am home. I do work for the World Health Organization as a chairman of a committee on the Chemotherapy of Malaria. I am on the National Cancer Advisory Board, which meets in Washington four times a year and reviews policies of the National Cancer Institute. I am on a panel for the Office of Technology Assessment which is supposed to advise Congress on matters concerned with basic research. I give lectures at universities all over the country, and abroad. I get roped into being on a lot of committees. I try to keep that at a minimum, unless I feel that I can do some good on them, because I think sometimes you get asked to do things simply because you have the reputation and not really because you can do some good. I don’t want to waste my time that way.

It doesn’t sound like a terribly relaxing schedule.

Gertrude Elion: Well, I relax. I go to the opera occasionally. I still have my Metropolitan Opera subscription after I don’t know how many years. It means going up to New York for the weekend, but I have friends in New York, and we enjoy it together. I enjoy traveling. I’ve traveled most of the world now. For example, I went to the International Cancer Congress in Hamburg last summer. I go to meetings, because I don’t want to stop learning.

What mystery would you most like to crack as a chemist?

Gertrude Elion: I would like to find something that is a cure for cancer, even if it’s not in 100 percent of people with that cancer. There is a secret still to be learned about the cancer cell, that we need to unravel. We certainly haven’t solved the problem in AIDS, but the cancer problem has been around for a lot longer, and it’s a lot of different diseases. It is a much more prevalent disease than it used to be because people live longer, and it is generally a disease that hits people in their 50s, 60s, 70s. These are people with useful lives still ahead of them. We need to put a lot more effort into cancer research. I am worried that we are beginning to throw up our hands and say, “There is nothing we can do about it.” That’s not true.

If you had had that attitude with viruses, we wouldn’t have the antiviral drugs we have today.

Gertrude Elion: That’s right. There are a lot of new leads and new information about what controls the cancer cell. If you find out what the key to the control of cell growth is, you could probably stop the cancer from growing. It may not have to be a toxic compound, it may just have to be a regulatory compound. That’s what cancer is, it’s a growth out of control. You shouldn’t necessarily have to kill the cell, if you could teach it how to get under control again.

Let’s go back to the moment you found out you were a winner of the Nobel Prize. Where were you, and how did you come to find out about it?

Gertrude Elion: I was getting dressed, It was 6:30 in the morning. A phone call came from a reporter, who said “Congratulations, you’ve just won the Nobel Prize in Medicine.” And I said, “Quit your kidding. I don’t think its funny. Whoever put you up to it, I think it’s a sick joke.” And he said, “No, really, it’s true.” I said, “I haven’t heard anything about it, how do you know about it?” And he said, “They put out a press release from Stockholm at noon Stockholm time,” which is 6:00 am New York time. I told him “I don’t really believe you. And he said I won it together with Dr. Hitchings and Sir James Black. And I thought, “I wonder where he got those names from.” I hung up, and a minute later, another reporter called. We went through this for the rest of the day. When I got on the McNeil-Lehrer Report that night, they said “When did you find out you won it?” And I said, “I still haven’t heard from the Nobel Committee!” Lehrer said, “Take my word for it, it’s true.” I did finally get a telegram the next day. They had been trying to reach me by phone, but the phone was constantly occupied. So that’s how I found out. I never finished dressing, before there was a reporter at the door from a local newspaper, and I’m trying to answer the phone, and trying to comb my hair, and the photographer is taking pictures, and some of those pictures are really weird.

Why were you so surprised?

Gertrude Elion: It just never occurred to me. For one thing, I had retired, the work had been done. I think Dr. Hitchings felt the same way. He thought, if they were going to give it to him, it would have been ten years ago, 15 years ago. I never thought they’d give it to me. I knew he’d been nominated because people would write me to ask for a copy of his CV (curriculum vitae), but I didn’t know anyone had nominated me. In any event, if they had, it was all in the past. So I had no reason to believe that in 1988 this would happen.

You had a couple of strikes against you as tradition goes, being a woman and not having a Ph.D.

Gertrude Elion: Yes. And being in industry. That’s three strikes. Very few Nobel Prizes have been given to people in industry. Some in physics, people working for General Electric, and so on. But in medicine, practically nobody. If you look back you will see this. And women, there… well, I was number five in medicine. There had been some in chemistry, and a few in physics. But industry is definitely not considered the place for discovery in medicine. So it was unusual in many regards. It was that. It was also… that generally they are given earlier in life for some one’s discovery, some sort of landmark thing. Not generally for a sort of lifetime of work. That’s unusual. So there were many reasons why it was not expected.

How many medical Nobel Laureates have not had Ph.D.s? I read somewhere that you were it.

Gertrude Elion: Gertrude Elion: That may well be. I’ve never looked to see.

These days, the big question is how to balance family and career. It’s a difficult juggling act, and many people are bewildered about it. How do you view that?

Gertrude Elion: In my generation, it really wasn’t feasible to have both. Partly because people wouldn’t hire you if you were married. If you had a child, that was the end of it, they didn’t let you come back. That’s all changed, and I think it is possible for women to have both, but I do think it’s difficult. I think some of them underestimate the difficulty. Something has to give part of the time, and you can’t expect to have everything. If people realize that, they can do it. I’ve had women who have children working for me in the laboratory, and many of them have done very well. Sometimes they had to take a break for a couple of years until the children were in school before they came back. I understood that. I think that was the right thing for them to do, if they felt they had to. But it is much more difficult for women. I don’t underestimate the difficulty. It’s probably worth it, but not everybody can do it.

There is an element of danger in chemistry. Did you ever have a scary accident?

Gertrude Elion: I had some minor accidents. One where I was pipetting something that I probably shouldn’t have been. It was a very thick solution of lye, and I got it into my mouth, and suddenly the whole lining of my mouth seemed to come off. Fortunately, I didn’t swallow any of it. It hurt for a couple of days. It was very scary. I never did that again. Usually, you are supposed to use a rubber bulb pipette when you are doing anything dangerous like that. It’s okay to pipette water, but that taught me a lesson. And another time I was doing a reaction in a glass tube, which was sealed, and I had it in a water bath. And I took it out, I looked at it, put it back, walked out the door, and the thing blew up into a thousand pieces. And I often thought, “What would have happened if it had happened in my hand?” I never did that again either. And other than that, I really was very fortunate.

What caused it to blow up?

Gertrude Elion: It was an alcoholic ammonia solution. Actually, it should have been in a glass tube, but the glass tube should have been in a casing to protect it, in case it broke, because it goes under tremendous pressure. We didn’t have anything like that in the lab, and it just never occurred to me that this could happen. And it happened.

You’ve worked with a lot of younger scientists over the years. What personal characteristics do you feel are necessary to be successful in this career?

Gertrude Elion: I think the first thing is to want to do it, to really feel that this is what you want to do. The other is not to let people discourage you by telling you this isn’t what you should be doing, or this isn’t what people of your kind do. I always quote Admiral Farragut, and say “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”

What problem now, in society, concerns you?

Gertrude Elion: I’m concerned about education. I’m concerned about peace. You can’t live in this world without realizing how many lives are destroyed needlessly. I think that we don’t put enough stress on education anymore. The kind of education that we used to have for young people had more discipline and made more demands on them. We’ve sort of let things slide and say, “We shouldn’t teach math. We shouldn’t teach Latin. That’s too difficult.” Children are very impressionable, they are very curious. You’ve got to take advantage of that curiosity, to let them realize that there is a big world out there they can discover. If you don’t do it when they are young, you are not going to get them back again.

You’ve done a lot of speaking out about protection of the rainforest. Why?

Gertrude Elion: I was in Brazil at a meeting, and I was interviewed by a reporter from Reuters, who asked me only questions about the environment. It’s not my specialty. I am very well aware that there are interesting medicinal plants in the rain forest that people have begun to discover. I also had taken a trip on the Amazon, on boat, and had seen the burning forests, and was very upset by that. All of this was being destroyed without any appreciation of what was being destroyed. So when I was asked about it, I spoke my mind.

And are we on the right track, then?

Gertrude Elion: I think people are beginning to appreciate the problem, but the problem is multiple. The rain forests are being burnt is because people need more room to live. On the other hand, they are destroying their livelihood. They are going to have floods, they are going to have problems with the air and so on by destroying all these trees. It’s a case of solving one problem by creating another one. It’s all very well for us to come and say, “You people are destroying your rain forests,” but they can say, “But we have to live. Where are we going to live? We don’t have any more space in the cities, we have to expand.” Unless somebody takes that problem into consideration, they are going to create a new one.

If you could come back in another life, is there any secret ambition that you would love to accomplish?

Gertrude Elion: I’d love to be an opera singer. I have a terrible voice. Essentially a monotone. As a kid, I can remember trying to sing and being asked if I really had to. I enjoy the human voice so much. I don’t think I’d really seriously want to be an opera singer. But that’s one of the things in my life that I’ve always felt very sorry about, that I wasn’t more musical, myself.

What is it about opera that is so wonderful?

Gertrude Elion: It’s a combination of music and drama. The emotions that one gets from listening to people who can act well as well as sing well is, I find, much greater than either one alone. I can cry over Madame Butterfly, and feel a kind of feeling I would never feel from seeing the same thing in drama, or just hearing music without the human voice.

Is there a composer you are especially fond of?

Gertrude Elion: Puccini, mostly. And Verdi… and Mozart.

Well, thank you so much. I’ve really enjoyed it.