That, in a nutshell, is that design.

It’s notable for its simplicity. Is less more?

Maya Lin: In that case, yes. For the way I work, absolutely. My goal is to strip things down, not so that they become inhuman but so that you need just the right amount of words or shape to convey what you need to convey. I like editing. I like it very tight.

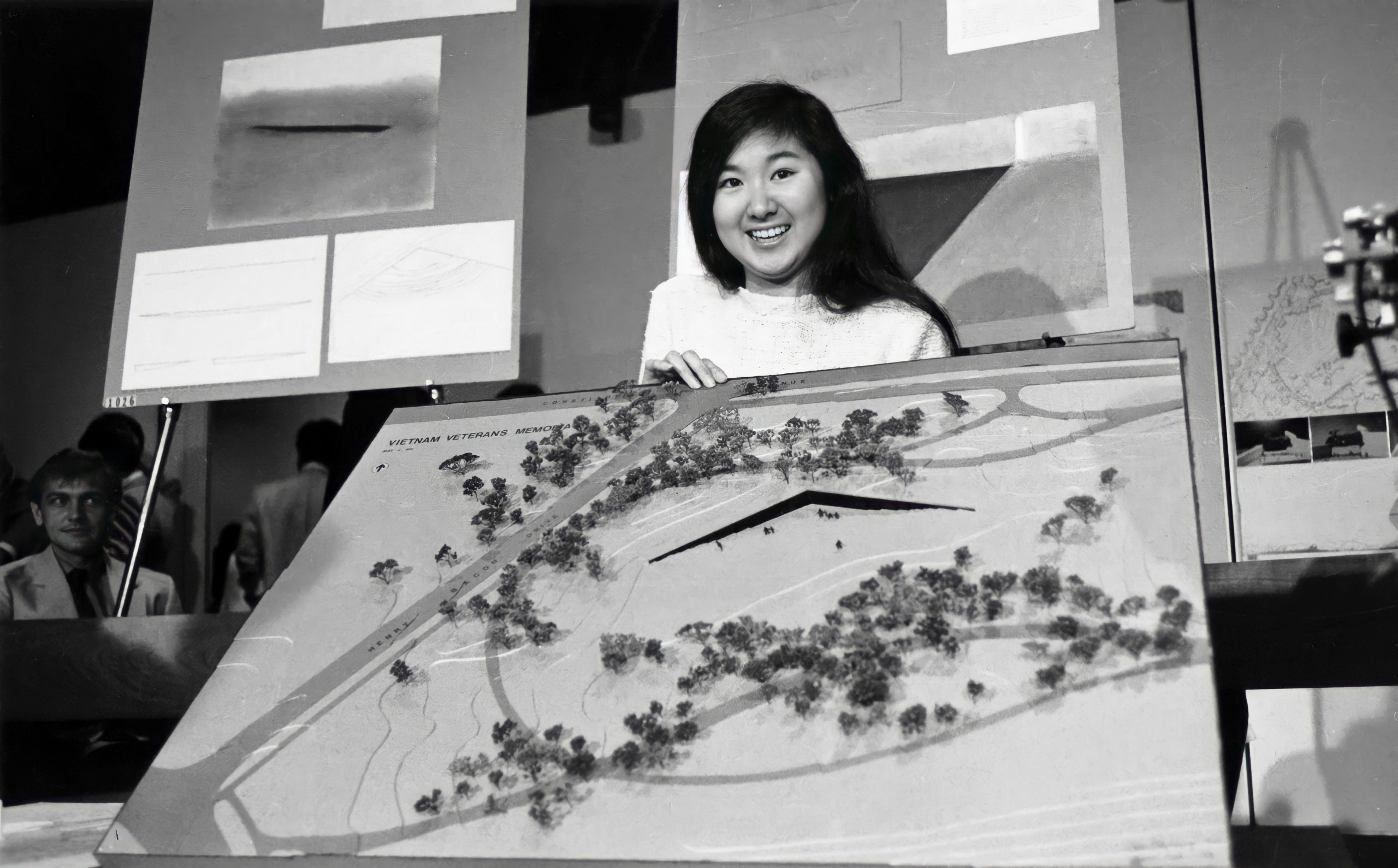

So your design for the Vietnam War Memorial was accepted, and then all hell broke loose?

Maya Lin: Not right away. It took nine months. Hell was breaking loose; I just wasn’t aware it was breaking. It didn’t even occur to me that it was a big deal. I had studied how competitions are handled in Washington. For the most part things never get built the way they were drawn. It is a small miracle that the memorial looks exactly the way it was designed.

You have to go through five governmental agencies two times for review. That’s normally where architectural projects get extremely modified, to put it kindly. I was amazed. Kent Cooper (of Cooper, Lecky, the architects of record) came up to me before my first meeting and he said, “Now be prepared. These people are going to be pretty tough on you.” I get in there and right away this tough architect on the Fine Arts Commission leans over and says, “Maya, is this what you want? Are you sure this is what you want? They haven’t done anything to change it.” These people are so nice! Everyone was so nice within these five legal correct channels. In fact, technically, if you look at it, there should have been no problem. The controversy was completely extra. President Reagan, Secretary of the Interior Watt, H. Ross Perot, all kind of got together and decided the design wasn’t right.

Secretary Watt withheld ground breaking until a technical compromise was met. By that time the Secretary of Interior was only supposed to check to see if the funding was in place, which it was. But Washington is political and full of compromises. So it was decided the three statues would be what was necessary. Now you have to understand, the walls are only 10 feet high, and they were proposing 14 foot-high statues that would go right at the apex. So we fought like hell, and the Fine Arts Commission was instrumental. We all knew a compromise had to be meted out. But exactly where was that compromise?

How difficult was it for you? You were only 21.

Maya Lin: It was difficult.

Suddenly all of this controversy was stirred up. They don’t even mention your name at the dedication ceremony. What hurt you most about that experience and the veterans’ reaction to the memorial?

Maya Lin: I completely understood why there was such a strong opposition to it. What a lot of people didn’t realize was that there was a requirement that all the names be listed. Ironically, that was something the veterans chose.

Now politically, deep down under you have two camps. And basically in American memorial art/architecture, the camp has always been the latter. It’s a little bit of denial: “I don’t want to see the dead. I don’t want to acknowledge that, because it’s too painful. I want the parade. I want the happy. I want the exalted.” And I think it was a very modern notion in a national capital to list all the names. That’s what was very controversial. Okay, it was black, it was below grade, I was female, Asian American, young, too young to have served. Or even the way I would talk, “Oh, I didn’t know much about the war. ” It was sort of like, “You have to be that person in order to understand those needs.” And I think none of the opposition in that sense hurt me. There were a couple of things that did hurt. I think the artist who did the three statues… as an artist to another artist, I didn’t understand that.

What did you take away from that experience? What did you learn from it?

Maya Lin: I probably went in there with more of an egomaniacal young artist confidence. And I actually became a little mellower. When you’re young you’re so idealistic and you’re so headstrong, or at least I was. I probably decided, “People are going to think I’m so egomaniacal because of the Vietnam Memorial,” that I tried to be a little bit more humble. My friends say I’m not at all more humble, so I don’t know.

As far as what I took away from it, at a certain point nobody would touch me with a ten foot pole. There were my lawyers, and there was one writer, a person who used to own The New Republic, who came to my support at one of the Senate hearings. No one else would touch me. I tried Yale connections.

I tried anything to try to protect the design. The AIA was wonderful, you know, the arts groups were. But you know, I was sort of like untouchable because everyone didn’t quite know how people would react to it. And then, a year later, when like the millionth visitor came to it, everybody wanted to say hello, that sort of thing. And I was a little jaded. My attitude is: I’m glad it’s a success. I’m glad people really are moved by it, that was its goal. But you do these things because you personally believe in it. And it was lonely. I mean, it was lonely being in this one testifying room where everyone else was on the other side looking at me like I was trying to deliberately hurt them.

It requires a certain amount of conviction.

Maya Lin: When you’re young, maybe that’s all you have. You have conviction. That’s valuable. Then you get experience and then you have less conviction. Maybe there’s a balance going on.

What was your childhood like, growing up in a small town in Ohio as the daughter of Chinese immigrants?

Maya Lin: It’s funny, as you live through something you’re not aware of it. It’s only in hindsight that you realize what indeed your childhood was really like. Growing up, I thought I was white. It didn’t occur to me that I wasn’t white. It probably didn’t occur to me I was Asian-American until I was studying abroad in Denmark actually and there was a little bit of prejudice — racial discrimination — because as I get a suntan I look like a Greenlander. And as the U.S. had a certain prejudice against Native Americans, the Danes had a similar read towards the Greenlanders, and all of a sudden they would be moving away from me on the bus. They wouldn’t sit next to me. There would be these weird comments.

Growing up, I think I was very naive about fitting in. In reality, I was not a participant in many school functions. Our home life was very close knit. It was my mother, my father, my brother and me. I never knew my grandparents on either side. When I was very little, we would get letters from China, in Chinese, and they’ be censored. We were a very insular little family. I really didn’t socialize that much. I loved school. I studied like crazy. I was a Class A nerd. My dad was dean of fine arts at the university, and when I wasn’t in school studying, I was taking a lot of independent courses at the university. And if I wasn’t doing that, I was casting bronzes in the school foundry. I was basically using the university as a playground.

I didn’t fit in in high school at all. And I don’t know if it was because I was different. I think it was my age. I looked much younger than most of my classmates, and in a way they were really nice to me, but almost as a baby sister. I think as a little girl there was a bit of a China doll sort of syndrome. They were friends and they were friendly, but I didn’t date. I didn’t really even begin to understand. I was really naive. So I studied and I loved getting A’s. I think I had the highest grade point average in my high school. And I loved to study, but I had no extracurricular activities. My activities were absolutely isolated. I would make anything artistic at home. And I think creativity and my artistic drive emanates from that childhood. In a way I didn’t have anyone to play with so I made up my own world.

Were you the oldest or the youngest?

Maya Lin: I’m the youngest. I have one older brother.

How did that affect you? Did it matter?

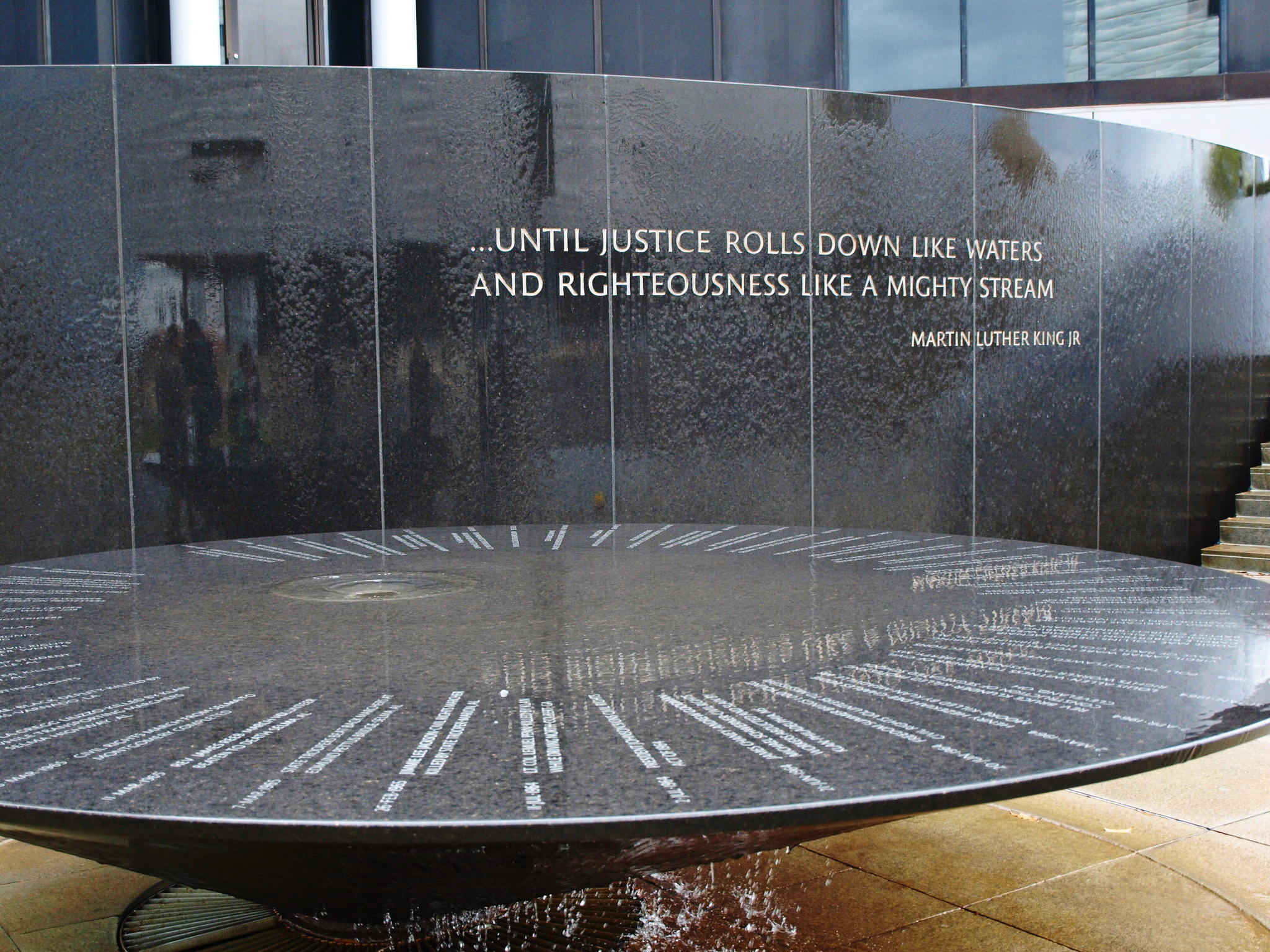

Maya Lin: Always tried to impress the older sibling. What does the older sibling do? Always try to humiliate the younger sibling. We had a very healthy sibling rivalry and fought a lot, and are best friends. We’re very different and yet we’re very close, in fact we collaborated on an art work of mine. He’s an English professor and a poet. We did a piece for the Cleveland Public Library called “Reading A Garden.” The centerpiece is a pool of water, and the title of the piece, “Reading A Garden” is spelled backwards but reflects forward in the water, which clues you in that this is a poetry garden. It’s a poem laid out three dimensionally. It’s all about words and the directionality and weight of reading. So we didn’t fight the whole time. Collaborating on a work of art — when you have two artists — is very tricky. It took us 30 or 40 years to get to that point!

Do you think your experience in school was a social circumstance or do you think you were really different? Even in high school you were a kind of super achiever, taking college courses.

Maya Lin: I had very few friends. I think my brother had a few more friends than me, but we stayed close to home, and I think we always ate dinner with our parents. We didn’t want to go out. I think the whole American adolescence was a lot wilder than I would have felt comfortable with. We stayed very close to home. I think it wasn’t just me. I think that’s Chinese.

We weren’t going to the proms or going to the football games, or doing anything of that nature at all. I don’t think I ever went to a football game, which at Athens High School was, you know, the Bulldogs were the Bulldogs! So there was a part of me that was like, “Oh, how many days do I have before I can get out of this town?” I mean, at one hand, you had a university there, so I could sneak out and take courses. But at the other hand, it’s Athens High, and it was tough to fit in, and I was aware of that by the time I hit my senior year. I basically was taking almost all of my courses independent study, and taking many of my courses at the university, and counting the days, ’cause I knew I didn’t quite fit in at that point and I was desperate to kind of get out of there, and you know, it was almost more instinct.

How do you think that experience affected you?

Maya Lin: I probably have fundamentally antisocial tendencies, let’s face it. I never took one extracurricular activity. I just failed utterly at that level. Part of me still rebels against that. You couldn’t put me in a social group setting. It’s different with a group of friends, but as far as clubs go — I’m probably a terrible anarchist deep down. My parents are both college professors, and it made me want to question authority, question standards and traditions.

How did your parents influence you?

Maya Lin: We were unusually brought up in that there was no gender differentiation. I was lucky as a girl to never ever be thought of as any less than my brother. The only thing that mattered was what you were to do in life, and it wasn’t about money. It was about teaching, or learning. There was a very strong emphasis on academic study within the family, especially on my mother’s side. I loved school, and all I wanted to do was keep going to school.

I think I went through withdrawal when I got out of graduate school. All my friends were going, “Phew, aren’t we glad it’s over?” but my whole world has been a college environment. I really respect people that focus their energies on education, on learning for the sake of learning. As a child, I was never told I couldn’t do something because I happen to be a girl. It’s what you learn up here, what you think up here. That’s all that counts —nothing else really matters.

How much of your family’s history were you aware of?

Maya Lin: Not much. I think it happened with the first generation of a certain era. If you talk to Asian Americans now, they’re probably brought up bilingual. Back then, our parents decided not to teach us Chinese. Now they’ll say that we weren’t interested, but I think part of it was they wanted us to fit in. It was an era when they felt we would be better off if we didn’t have that complication. Ten years later, it had already switched. Now you want both cultures when you’re very young. I think 30 years ago, it was more like, “Oh, let’s make you comfortable in your new climate.

I’ll say, “Oh, you didn’t tell us much about your family history,” and my mother will say, “Oh, you never asked.” And I think in that is a key. I would probably venture to guess that they didn’t speak much about it because, in a way, it might have been painful for them because they had to leave all their family, all their friends. And because they weren’t going to be offering it up, we didn’t ask. And I think it actually got me into a lot of trouble later on. Like say, for instance, when I was building the Vietnam Memorial, because I never once asked the veterans, any of the group that I was working with, “What was it like in the war?” Because from my point of view, you stay reserved. You don’t pry into other people’s business. They, I think, in turn, were hurt that I didn’t ever seem interested in their lives. I think again, that is very much a part of my upbringing. It’s very hard for me to ask people, unless they offer it.

I didn’t find out more about my family’s history until later. There’s a wonderful part my father told me on my 21st birthday, after we were in Washington. There was a party at the Chinese embassy, and my father was going on and on with the Chinese ambassador; they were just talking and talking. And afterwards I said, “What were you talking about”? and he said, “We were talking about my father.” It turns out my grandfather, on my father’s side, helped to draft one of the first constitutions of China. He was a fairly well-known scholar.

Then it turns out one of my father’s sisters and her husband were Lin Hui-yin and Liang Si-chen, who are these very well-known architectural historians in China. They actually studied at the University of Pennsylvania, brought modernism back to China and helped design Tienanmen Square. They realized later on that they should be preserving more of the old than the new, but by that time it was too late. They helped bring modernism in, but at the same time they put together a manuscript documenting all the architectural temple styles of ancient China. The manuscript was lost, and then Wilma and John Fairbank found it years later and published it. Wilma Fairbank just published another book on Liang and Lin. They were written about in Jonathan Spencer’s book, The Gate Of Heavenly Peace. I knew nothing about my aunt, who was this architect.

On my mother’s side of the family, one of my great-grandmothers was one of the first doctors in the Shanghai region. In fact, as I was having our first child, I had a doctor at New York University, Dr. Livia Huan spelling? who’s from Shanghai, just like my mother. Dr. Huan started speaking to my mother, and it turns out that Dr. Huan’s father, I think, was delivered by one of these two sister doctors in Shanghai — my great-grandmother or her sister. So it’s this very strange world that comes together, and connects, and then disconnects. But I didn’t really ask much about it, growing up.

Were you more preoccupied with trying to be American?

Maya Lin: I think I wanted to fit in. I didn’t want to be different. I probably spent the first 20 years of my life wanting to be as American as possible. Through my 20s, and into my 30s, I began to become aware of how so much of my art, and architecture, has a decidedly Eastern character. I think it’s only in the last decade that I’ve really understood how much I am a balance and a mix. There’s a struggle at times. I left science, then I went into art, but I approach things very analytically. There’s the fact that I choose to pursue both art and architecture as completely separate fields rather than merging them. I sometimes think the making of architecture is antithetical to the making of art. Then there’s the East/West split. I think a lot of it is a struggle because I come from two heritages.

Does being aware of that make it easier or more difficult to do your work?

Maya Lin: Neither. It might make me feel a little more whole and peaceful after the fact, but it doesn’t really change. The process I go through in the art and the architecture, I actually want it to be almost childlike. It’s almost a percolation process. I don’t want to predetermine who I am, fanatically, in my work, which I think has made my development be — sometimes I think it’s magical. Sometimes I think I’ll never do another piece again. But basically you don’t know who you are. But yet I feel much better as I’ve hit the 40’s, so to speak — it’s sort of frightening to say — that I’m more whole because I understand. I’m more at peace. I’m not fighting it. I was fighting it in my 20’s, really hard. I mean, it was a real — there was an anguish in that. I mean ironically, the work is much more peaceful. All my work is much more peaceful than I am, and maybe the work, in that sense, is trying to find a resolution between what was probably a struggle.

Aside from your parents, were there any other people in your life who inspired you or motivated you?

Maya Lin: I would say there were many influential teachers. A funny phrase comes to mind, it’s an awful phrase: teacher’s pet. And yes, I was one of those. The other kids probably hated me. That’s probably why I didn’t have any friends. I really enjoyed hanging out with some of the teachers. I remember this one chemistry teacher, Miss McCallan. I liked making explosives. She liked hanging out. We would stay after school and blow things up.

One time I made this incredible powder, flash powder, and I made way too much of it. And I remember I was working out of a crock that must have been this thick — walls. And it exploded! I mean it was bad. It was stupid, stupid, stupid of us. And I couldn’t hear. Like it was loud. It was louder than a rifle report. And the head science teacher comes in, a very serious man, and he’s looking around. And he’s going, ‘What did I just hear?” And we were deaf at that point. We couldn’t hear anything. And we went, “Nothing, nothing. I didn’t hear anything. Did you?” And so what you don’t realize, I think, is that some of your teachers are actually closer in age to you than you think. And so there’s supposed to be this distance, but by the time I was a senior in high school, she was maybe four or five years older than me, maybe a little older. But we had a lot of fun doing that. There were other teachers; both my art teachers were just wonderful throughout. I really enjoyed my whole educational process. And it was fun. That’s what I actually thought was really fun. So yes, there were many influential people.

Was there anything you were bad in as a student?

Maya Lin: Gym. I failed. In fact, that was the only teacher, I think, that really disliked me, and I disliked her just as much. We won’t name her. I was really good at track, but anything else in gym, just shoot me. I was the smallest in my class. When I was little you play that stupid game where they pick teams or you would have to break through the line and nobody would want me on their team because I was half the weight of everyone else. There was no way I could break through the line. From that moment on, anything involving gym was like, “Get me out of here.”

Were books important to you when you were growing up?

Maya Lin: I read like a demon. If I’m working on an art work, I tend to daydream when I’m reading so I can’t read when I’m working on a few projects. So I would take summer breaks, in between work, and then I would just devour books voraciously. Like one year back from college I think I read nothing but Nietzsche. Another summer was Nabokov.

When you were a kid, what books did you read that excited your imagination?

Maya Lin: The Hobbit, the J.R.R Tolkien series, The Narnia Chronicles, anything that was science fiction, or fantasy related. I have the most obscure science fiction/fantasy collection that you could possibly have. The Gormenghast Trilogy by Mervyn Peakes, top that! It was actually really awful, but yes, I read it. I think I had shelves and shelves of this sort of pseudo sci-fi, not hard core sci-fi, but sort of in between science fiction and fantasy. That’s what I pretty much focused on if I wasn’t making something, which I was mostly doing.

So how did you feel when you finally left home and went to Yale?

Maya Lin: I was probably the first kid in my high school to go to Yale. And you know, Athens, Ohio, town of 15,000. I applied almost as a lark. I didn’t know where I was going to go to school and I got in, and I was just so happy, and it was really surprising. And then, when I got there, the whole shock of being in a way not as well prepared academically for an Ivy League school and learning that you were the dumbest person in your class, not the smartest. No, it was very, very, intimidating. And it was also funny because my — as I started to really focus on art and architecture, my roommates were appalled. Like one semester I never went to the library. I mean, I was pulling all nighter after all nighter obsessing about this project or that.

My brother to this day hasn’t forgiven me that I didn’t take a history course. I always took soft history courses like sociology. I think if I could do it all over again, I really missed out on some great courses. But in art or architecture your project is only done when you say it’s done. So if you want to rip it apart at the eleventh hour and start all over again you never finish. And I was one of those crazy creatures. The saving grace is I still got a fairly solid liberal arts undergraduate education minus the history, which I’m still regretting.

I really sometimes question students who have chosen to go into like an architecture school from day one, because I think they’re missing out on the English courses, the science courses, the math courses. If you can afford the time to do graduate and undergraduate, I would broaden your mind in undergrad and then specialize. Because I think for both art and architecture, you have your whole life ahead of you. Don’t think that at age 18 you want to like just focus in on your own personal world. It’s like, open it up for a while. I think it’s invaluable.

It’s this whole thing about public school versus private school. It was tough, and yet I wouldn’t have wanted to go anywhere else. A lot of my classmates went through an incredibly rigorous, competitive high school for four years, but by the time they hit sophomore or junior year, they were so tired. I am actually glad I didn’t have any of that. I wasn’t obsessing about my SAT scores or my PSATs. I loved getting straight A’s, but that was more for me. Now I look at the pressure kids go through in high school!

You should be having more fun in high school. You should be exploring things because you want to explore them and learning because you love learning, not worrying about the fact that, “Oh, at this private school only three are gonna go to that school.” That’s tough competition. We have two young children, so we’ll have to go through this debate.

When did you realize what you wanted to do in life?

Maya Lin: Oh, about five years ago, seriously. I loved animals when I was growing up. I thought I was going to become a veterinarian. Then I sort of switched. In high school I was definitely going to become a field zoologist because I love animals and I love the environment. Half the kids I went to school with would say, “Oh, she’s going into science.” The other half would say, “Oh, she’s going into English”. My mother is a poet and English professor. My dad’s a ceramicist, and a Dean of Fine Arts. I was always making things. But it was always very academic and none of this connected. Even though art was what I did every day, it didn’t even occur to me that I would be an artist.

Then I get to Yale and my advisor is a science advisor because I have specified my interest is field zoology and animal behavior. I actually wanted to go out in the field and understand why animals are what they are. It was Dr. Apville, who I still talk to every now and again, and he says, “Yale’s animal behavioral program is probably not what you’re going to approve of.” And I said, “Well, why?” He said it’s neurologically based and that it dealt with vivisection. I didn’t even know what vivisection was, but it basically means dissecting the animals while they’re still alive. I looked at him and I said, “You’re absolutely right. Ethically there’s no way.”

Though I was actually tracked pre-med at that time, I thought, “This isn’t going to work.” Then I thought of architecture because I thought it was this perfect combination of art and math, art and science. In high school, two or three of the independent courses I took at the university were teaching myself Fortran, Basic and Cobol.

I loved logic, math, computer programming. I loved systems and logic approaches. And so I just figured architecture is this perfect combination. Then it takes me seven years of architecture school to realize that I think like an artist. And even though I build buildings and I pursue my architecture, I pursue it as an artist. I deliberately keep a tiny studio. I will hire firms or cause firms to be hired to work with me. I don’t want to be an architectural firm ever. I want to remain as an artist building either sculptures or architectural works. And in a way what I disliked about architecture was probably the profession. I still am an artist. And basically what does that mean? It’s much more individual. It’s much more about who you are and what you need to make, what you need to say for you. Whether someone’s going to look at it or not, you’re still going to do it.

Can you generalize about what you’re striving for in your work? You deal with some very important ideas: women, peace, civil rights, environment.

Maya Lin: I think there are two things going on. One, because my parents were both educators, I might be making up for all the history courses I didn’t take, through these larger issue subjects. Two, it is a way we can teach the next generations. It’s this need in me to help out, whether I’m doing that or whether I’m volunteering for some environmental organization.

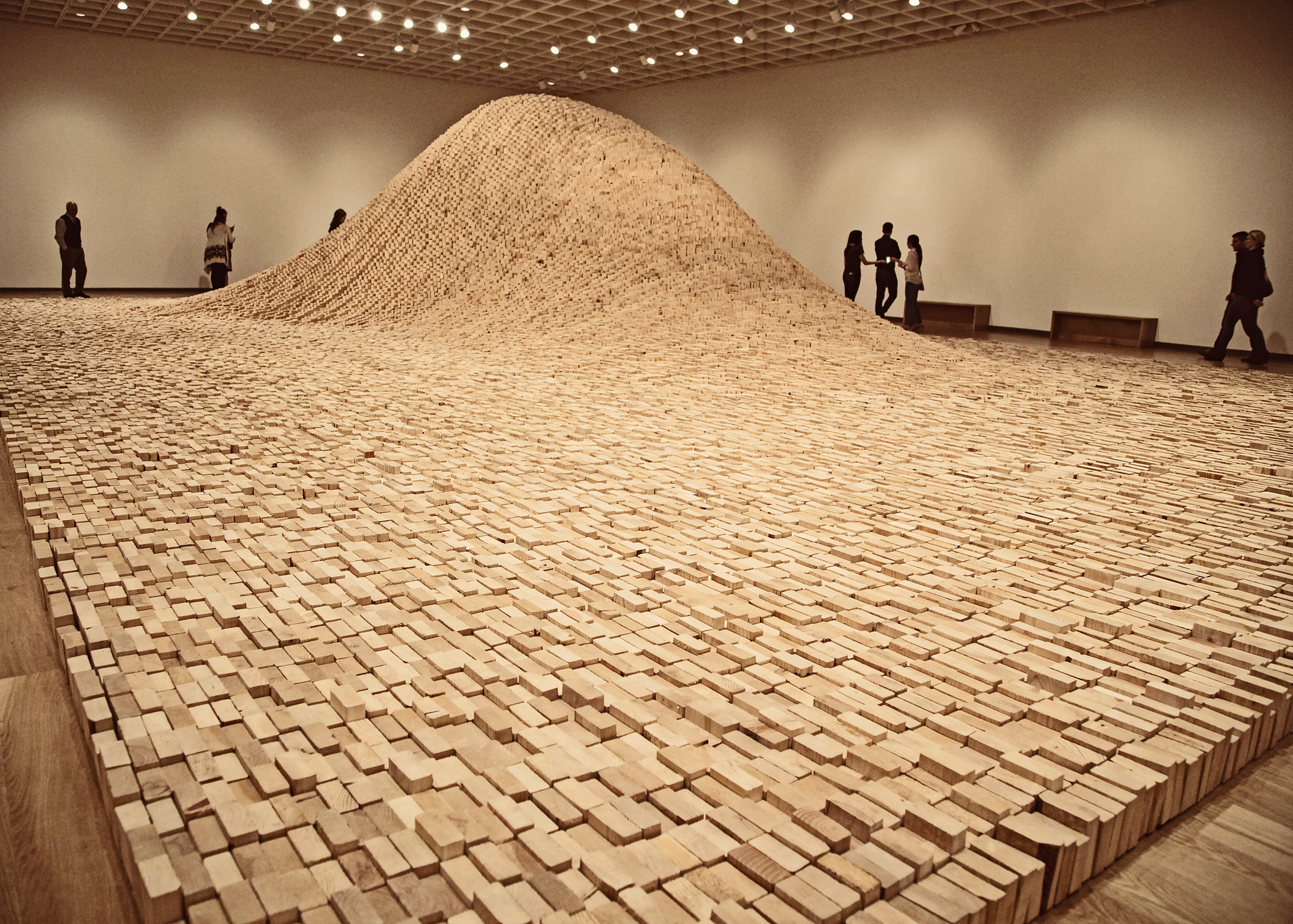

The other side of me is solidly pursing art and architecture out of my own drive. Not that the monuments aren’t also part of that aesthetic, but the monuments in general draw on a larger social issue. The art works deal much more specifically with my personal love of landscape, the environment, how we see the land through a microscopic view, a satellite view of the Earth. That’s my art. And there’s been a very strong progression in the last ten years as that’s developed. There’s a show called Topologies that went throughout this country — part of it’s traveling in Europe right now — which deals with a love of nature, naturally occurring phenomenon but seen through a 21st Century lens, the lens of technology. So it’s a landscape art, compared to 19th or18th Century landscape painting. We have a couple of different technological ways of viewing our world. I play off that in my art.

I think art is very tricky because it’s what you do for yourself. It’s much harder for me to make those works than, in a way, the monuments or the architecture because those have functions. Architecture, the monuments, it’s a symbolic function, but it’s still you’re solving a problem. The architecture, you’re definitely making art, but it’s surrounded by a problem solving. It’s like math. It’s a puzzle to me. I love figuring out puzzles. The art work, on the other hand, is, “Go into a room and make whatever you want to make.” And it’s very, very hard.

What is the role of art in society?

Maya Lin: The role of art in society differs for every artist. I try to give people a different way of looking at their surroundings. It’s making people aware of nuances, changes in depth, height, making you aware of perceptions in a very, very subtle level. Focusing you on a new way of looking at your surroundings, at the land. That’s art to me.

I think what makes art valuable is: it is about an individual expressing what they think is a part of them, and variety and difference and clashes is what makes art valuable, that there is no one defining idea of what art is or what it should do. And that’s what makes it art, that it has no rules, that it’s so individualized in that sense. And yet, because we are born and we come from a very specific time, it is a reflection of exactly who we are at this time without ever having to be consciously thought of that way. It just is.

Should it provoke? Should it make people think?

Maya Lin: Some art should. Other art might not. Some artists want to confront. Some artists want to invoke thought. Some artists want to please in a different way. They’re all necessary and they’re all valid.

If I read correctly, you once said that you don’t want to tell people what to think, you want to present them with information. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Maya Lin: That probably is very eastern. It’s the idea of the well. You take from the well. You offer up information, but you have to let the viewers come away with their own conclusions. If you dictate what they should think, then you’ve lost it. That’s not the goal. I think that is very much an Eastern approach.

At this point in your life, what haven’t you done that you would like to do?

Maya Lin: I think I’m very young, architecturally. Because I spend equally as much time in the art, I can only take on one or two architectural projects at any given time. So my career in architecture will take twice as long, maybe three times as long. There’s a project on extinction which I’m starting now, but I’m not in a hurry to do a lot of projects. I am very resolved in each project I take on. In the art work, I have sort of made myself whole, so there’s a sense of arrival. I’m very curious to see where I go next with landscape. The architecture is younger.

I’ve had very few free standing projects. And I’m working on one right now, a bakery for the Grayston Foundation. They’re a not for profit group that build housing for the homeless, AIDS hospices. This one bakery in particular hires, at times, people out of prison, but also other people in sort of economically hard neighborhoods. And I am drawn to institutional, not-for profit-museums, educational. I did a library for the Children’s Defense Fund. I’m working on a chapel for them. I’m interested in keeping the balance between the art and the architecture. And I think that is the goal, to keep it up, to build, make more works, see where I go with it, not lose one to the other. I think a lot of the architectural works will deal with being environmentally sensitive, sustainable, using solar passive cooling. They’re very simple, with a warmth isn’t what minimalists are thought to have. There’s a humanness, an intimacy, a real warmth to the simplicity. But again, can I reduce it? Can I keep it to clean-powered all natural materials?

One of the key things in the architecture is that I want always to have you feel connected to the landscape so that you don’t think of architecture as this discrete isolating object, but in a way it frames your views of the landscape, which is a very Japanese notion. So that the house is a threshold to nature, or basically begins to explore our relationship to nature. So again, this love of the environment comes back through all the work.

What do you say to young men and women who might come to you and ask, “How can I do what you do? How can I become an artist?”

Maya Lin: You have to work very hard. I don’t know how many days and nights I’ve spent. I think you have to be forever questioning what you’re up to. I think you have to have conviction and at times completely question everything and anything you do. I think you have to understand that no matter how much you study, no matter how much you know, the side of your brain that has the smarts won’t necessarily help you in making art. That’s a frightening notion. Nothing you learn will help you in being creative. In fact, at times it could hurt you if you think too hard. Sometimes you have to stop thinking. Sometimes you shut down completely. Every time you do that, you’re afraid you’ll never start up again. I think that’s true in any creative field. Nothing is ever guaranteed. Nothing is ever a sure thing and all that came before doesn’t predicate what you might do next.

Looking ahead at the 21st Century, what do you see as the greatest challenges we face as a society?

Maya Lin: How we are using up our home, how we are living and polluting the planet is frightening. It was evident when I was a child. It’s more evident now. I think we have had a bad habit, as a species, of thinking of ourselves in our separate little pods. And those pods went from being the village, to being the country, to being — you know. And now we have to think in terms of environmental solutions, in terms of a global outlook. If we’re going to be making pesticides illegal in this country, but then shipping those same chemicals down to other countries because they don’t have as strict an environmental law, that is a crime. That’s got to stop. We have to take responsibility and we have to start solving these problems on a global outlook. And yet we have no mechanisms to govern on an international level really. That is what is going to be key.

I completely believe in what’s happening with the greenhouse effect and with the ozone layer. Only x percentage of the population are contributing to those pollutants. What happens when the rest of the world modernizes? Can we learn from our mistakes before we make them in another country? Does one country have a right to say that to another country? I think in the next 10, 20 years, if we don’t have a much stronger concern for the environment on a very political level, we’re in trouble. We are in trouble. Yet everyone focuses on the economy or individual prosperity. We have to figure out how we can deal with this.

What does the American Dream mean to you?

Maya Lin: To me the American Dream is probably being able to follow your own personal calling. And to be able to do what you want to do is an incredible freedom that we have. It provides for opportunities that you don’t get in that many other countries. I think the American Dream also represents that we have a responsibility to share it, and to not just sort of hoard that freedom, but hopefully share that freedom with other countries and with people within our own country that don’t have that freedom.

Does the artist have a responsibility to society?

Maya Lin: Artists have responsibility to themselves as individuals. It goes back to diversity and variety. Some artists might want their work to be socially focused. Other artists won’t. You need both; otherwise you kill art and we all lose out.

Thank you very much.

Maya Lin: You’re welcome.