Your English is virtually unaccented and perfectly fluent, and you write in English. Where did that fluency come from?

Khaled Hosseini: I think part of it is youth. Farsi was my first language. I learned French when I was eleven, and we lived in France for about four years, so that became my second language. And then we moved to the States, and I was 15 at that time, so I began to pick up English. Actually, I picked up English pretty quickly, probably within a year I was pretty fluent. And part of it is that you’re still very pliable mentally at 14, 15 years old. You still are not fully rooted in that, so you still have that ability to absorb things in a kind of a childlike way. And so I picked up the language pretty quickly. And I think part of it also is that I always had kind of an ease with foreign languages. I always had an ear for it and seemed to pick it up more quickly than some of my friends and fellow students. So I think it was a combination of both things.

As a teenager in America, you really have to learn the idiom, you have to learn the slang fast so you can fit in, right?

Khaled Hosseini: Fitting in in the U.S. when we first moved here — boy, that was quite a difficulty, because I moved to the States when I was 15, and 15 is a strange enough age, regardless of who you are and where you are. And this is a strange enough age if you’re in your own environment, and you are growing up, and you still feel alienated and isolated, and you feel like the world is against you and so on.

You are neither a child nor an adult.

Khaled Hosseini: It’s a cliché, but it’s really true. You really are kind of searching for who you are. You have gone through this period of metamorphosis, both physically and emotionally, mentally in every way. But it’s that much more tricky when you are 15, and you have abandoned everything that you are familiar with, and you have come to an environment where you don’t speak the language, you don’t understand the ambient culture, and you feel completely at a loss.

I went to high school — my family moved to the U.S. in September of ’80, and two weeks later, I was in high school in a regular English language class. I will never understand why I was never put in ESL, but I spoke virtually no English, but I was sitting in this English class, and it was pretty much sink or swim. So that’s how I learned English really on the fly like that. I just had to learn it — there was no choice. But in terms of fitting in, I felt like a complete outsider. I felt like I was like looking in through the glass at a party that was going on, and I wasn’t invited to it, I didn’t really understand the behavior and the mores of high school, all of the different cliques. I felt like — the only people that I kind of connected with at that time were other refugees, and there weren’t that many Afghans at that time, as I said. There were only a handful of families at that time. There were a lot of Cambodian refugees, and I became friends with them. Probably my first year of high school I hung out with them and hardly any of them spoke any English, and they were speaking Cambodian among themselves. But I kind of felt natural for me to be among them. Gradually other Afghans came and I learned English and made friends, but I never felt, I never really felt like I ever belonged in high school.

Can you talk about the decision to write your novels in English? For an America-born person, that would be akin to saying I think I’m going to walk on the moon. I’m going to write a novel in my third language.

Khaled Hosseini: When I started writing The Kite Runner, the novel, which was in March of 2001, by then I had been in the States for over 20 years. So English had become a very, very natural language for me. I felt very comfortable with it. In fact, I had been writing short stories in English by then for almost two decades. So I felt at ease in the language and it felt — my default setting for storytelling was English. I began writing when I was a kid in Farsi, and when we moved to France, I dabbled in writing in French. But at this point my prose voice, my fictional voice, the rhythm and the cadence and everything that goes into creating fiction, for me all of that, my setting, I was in English. So that is the language that I feel most natural with telling stories.

You ended up going into biology. Talk about that.

Khaled Hosseini: Deciding to pursue a career in science, specifically medicine, was very much a rational decision. When my family came to the States — from a fairly affluent background in Kabul — but when we came to the States we were political refugees. We had lost all of our belongings, our land, everything that we owned was gone. We had suitcases of clothes, and that was about it. So when we came to the States, my family was on welfare. I think that was a very difficult adjustment for my parents, because they were always kind of on the giving end of charity, and now suddenly they were on government sponsored aid, which was a real embarrassment for them, I think. I remember how ashamed my mother was when we would go to the grocery store, and she would pay with food stamps, and her big worry was that a fellow Afghan would see her doing that, and she would be mortified at the thought of it. So in that environment, I felt, my parents told us, “Look, this is our life now. We’re going to work, but you guys have to study. That’s what you have to do. You have to make something of yourself. We came here because there is opportunity for you guys here, and we want you guys to make something of yourself.” And at that point, the thought of pursuing writing or something, to be honest, it never even crossed my conscious mind. It seemed so unachievable, so outlandish that in that kind of an environment where you feel like you have to become something, you always have this fear of economic instability, you always have a fear that you’ll end up homeless or dependent.

Did you think trying to be a writer was self-indulgent?

Khaled Hosseini: Self indulgent, frivolous, almost. It seemed ridiculous. And so I never — not to mention that I didn’t speak the language. So I decided early on that I would pursue sciences. I had always been comfortable with the sciences, and I decided on medicine, biology for college, and eventually medical school, because I felt that was a profession where I would be good at it. It would provide me both financial and professional stability forever. And I felt that was a sensible thing to do. As I said earlier, I was always very sensible. I was never ever really a great risk taker. And so I went to medical school, but it was really more of a rational decision. Like a lot of, I think, first generation immigrants that come to this country and end up somehow as over-achievers, I think that’s what happened to myself and my siblings, too.

Did they become professionals in their fields?

Khaled Hosseini: Yes. I have a sister who is a vice-president of sales at a company. I have a brother who got his master’s degree in physics and electrical engineering at Stanford. I have a brother who is a chiropractor. They all pursued their dreams and did really well.

Were there teachers that were particularly important to you after you came here?

Khaled Hosseini: I had really good teachers in high school. Probably I connected the best with an English teacher that I had my junior year in high school, Miss Sanchez, Jan Sanchez — God bless her. I’m still in touch with her, had lunch a couple of years ago, and we email each other and still exchange, recommend books to each other: “What novel are you reading lately? I read this book — you want to read this.” That kind of thing. But she really was the first time — I remember it was in her class that I read The Grapes of Wrath, which was the first time I had read a novel in English where I felt like I got it at the time. I had the, I felt really connected to the writer and to the story. I told her how much I loved that book and what it meant to me, and I think I saw part of my own family, and a lot of the Afghans in that story — people who would, they become uprooted and homeless and kind of drifting around trying to find a new home. So Jan Sanchez was probably my favorite teacher in high school, and although I never shared with her any of my writing, she came to one of my book readings as a surprise. I hadn’t seen her in over two decades, and she showed up, and she goes, “Remember me?” Obviously, I knew immediately who she was, and it made me so proud that she had read my book and she had loved it. I felt like I had done good. You know, when your teacher comes up to you, even if you are middle-aged and have your own family, having your teacher come up to you and pat you on the back is still a pretty special feeling.

Did your parents’ economic situation stabilize after they arrived in the U.S.?

Khaled Hosseini: Yeah, I mean, they worked really hard. My mom, who was a vice principal of a high school in Kabul, started getting a bunch of jobs. I remember she worked the grave shift at a Denny’s, where she was a waitress, and my dad would take all of the kids in our new used car, and we would go to see my mom and sit in her section, and she would serve us ice cream sundaes. But she did that for a while, and then she had a bunch of other jobs. Eventually she studied cosmetics and became a beautician and worked at a little hole-in-the-wall salon in East San Jose for close to 20 years until she retired a few years ago. My father worked — God, he held a bunch of jobs — he worked on an assembly line, he worked, he tried to sell insurance, he did a bunch of different things. Eventually he became a driving instructor. He was a driving instructor for years, and his specialty was teaching the physically challenged how to drive. So he had these vans, and the school had given him this van that came with all of these lifts and levers and all of these gadgets, and he would pick up the students and then drive them up and down the hills of San Francisco and teach them how to drive. And then eventually he found a job with the City, the County of Santa Clara ironically enough, as a welfare dispenser to recent immigrant families. So he was then back to the role of dispensing aid and charity to people who needed it. And he worked that for 15, 20 years until he also has retired.

Did you and your family face prejudice here in America?

Khaled Hosseini: I can’t say there has been an instant where I felt anything. And I don’t think I’m aloof or dense about it. Quite the opposite.

I thought that maybe when September 11th happened — I said to myself that morning — especially after it became clear that the Taliban, who were then in Afghanistan, had had a hand in it. At that time, I said it hasn’t happened in 21 years, but now we’re going, now we’re going to feel something. People are going to say something. I was a practicing, a full-time practicing physician at that time. And then the next — when I went back to work and my voicemail was full — and it was calls from my patients, some that I had seen maybe once, some that I had seen a couple of times, some of my more chronic patients. But all of them had left messages for me. You know, “We hope that you’re not being harassed. We hope you’re okay. We hope you know nobody blames you, your people.” It was really kind and gracious. I never felt, my family nor I never felt personally attacked in any way.

So what direction did you take in medicine?

Khaled Hosseini: I went to general medicine. You know, you have a chance to dabble into a little bit of everything in medical school — surgery, pediatrics and so on. But I like general medicine, because it seemed to me rather than surgery, it seemed to be more of a people and more of a social work. And surgery, it’s skill-driven. Most of internal medicine, primary care, is really a people skill. It’s the — the science of it is pretty easy to pick up, it’s the art of talking to people, being able to hear what they are really telling you, what they are not saying but what they are really trying to tell you. Knowing how to break bad news, knowing how to handle grief and anxiety and fear and those things. That’s really what separates a competent doctor from a really great doctor. And that’s what was attractive to me about internal medicine. So I went to internal medicine and practiced for a total of eight and a half years as a primary care physician, first in Southern California and then in Northern California.

Where were you in Southern California?

Khaled Hosseini: I trained, I went to medical school at UC San Diego. I trained at Cedars Sinai in Los Angeles and then was in practice in Pasadena for three years. Then my wife and I decided to move back up north to be close to both of our families, and we were thinking about starting a family and so on. So we moved back to the Bay Area, and I worked in the Kaiser system for five and a half years. I worked in Mountain View in the South Bay.

Was it rewarding?

Khaled Hosseini: Absolutely. I had a rough time of it at first. The first few months were very difficult for me, and there were days when I thought I had made a very, very big mistake. It’s overwhelming to suddenly be responsible for people. As a medical student, as a resident, you always have the luxury of having the attending who takes the ultimate responsibility and cosigning your orders and so on and so forth. But when you have your own practice, suddenly there is nobody behind you — you’re it. And so that — and every young doctor feels this. That first day at work when they worry that they did the wrong thing or they — should I have sent that patient home, maybe I should have sent him to the ER. You know, you are kind of wracked by those anxieties, but eventually you get the hang of it. And I grew into medicine, and it became a very rewarding career for me. I grew to like it over time. It wasn’t love at first sight at all. It really took me a few years to really grow into it and to really appreciate it. In fact, by the time I left medicine, which was in December of 2004, is when I was most at peace with my career and when I was enjoying it the most. But at that time, I had to leave.

When you were practicing medicine, did you still feel the pull to write fiction?

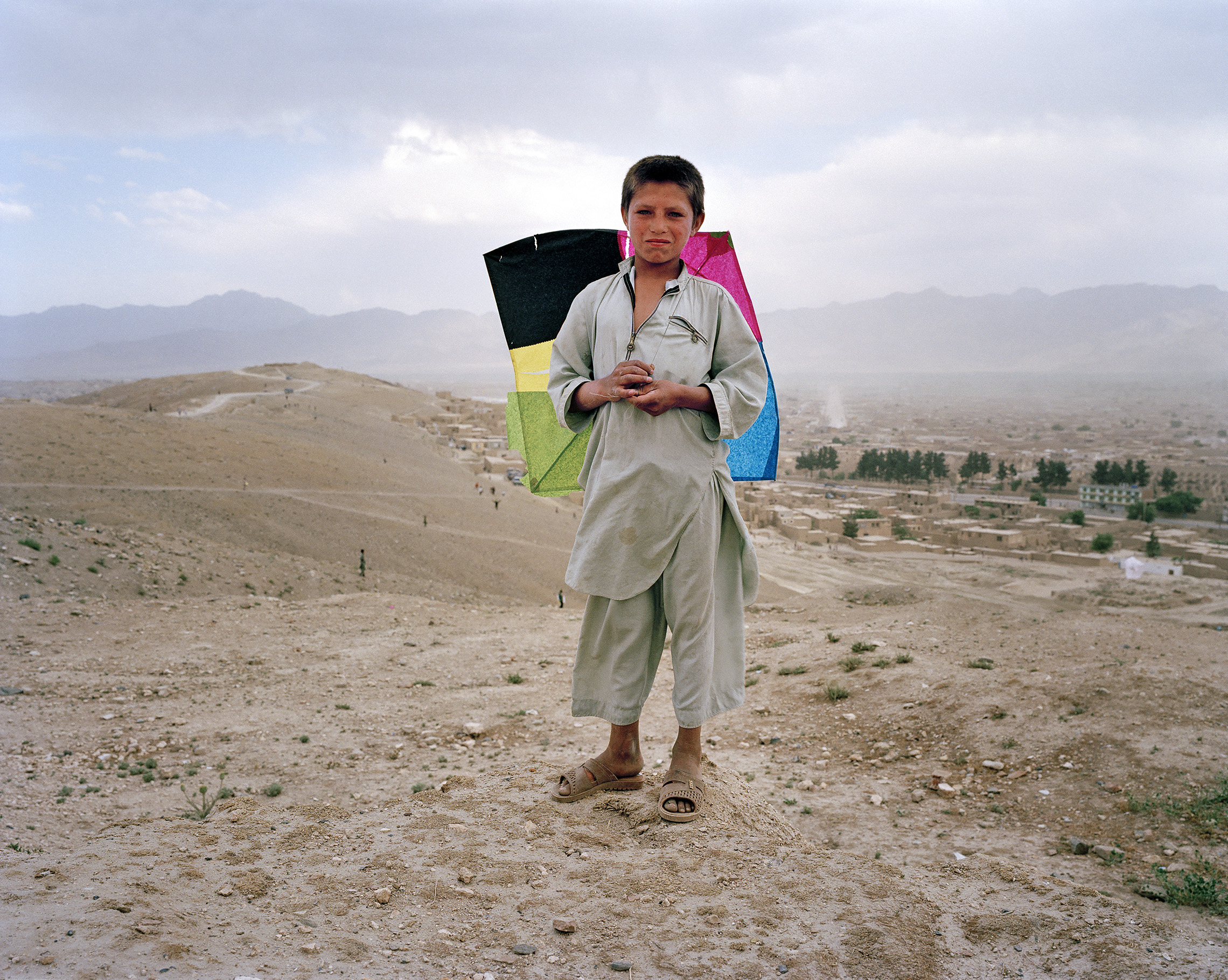

Khaled Hosseini: Well, I had been writing most of my life. I started as a kid in Kabul and wrote steadily most of my life, with the exception of the four years of medical school and three years of residency, which really takes away everything from you. You basically are slave to your schedule. But I had been writing as a hobby, as a way of just personal reward for years. And I happened to write a short story called The Kite Runner back in the spring of 1999. I had seen a story about the Taliban banning kite flying in Kabul, and since I grew up in Kabul flying kites with my brother and my cousins, my friends, it struck a personal chord, and I wrote a short story, which I thought was going to be about kite flying, and it ended up being about something altogether different. And that short story sat around for two years until March of ’01 when I picked it up, and my wife found it and read it and she loved it. I went back to it, and I realized, “Wow! I think there is a novel in this thing.” And I had been thinking about writing my first novel for years and never had the courage to, never had the right material. I said to myself, “I think this short story is very flawed as a short story, but it could make maybe a good novel.” And it kind of was a personal challenge to finally write that first novel, and I began writing it.

In your spare time?

Khaled Hosseini: Well, what passes as spare time. I was working full-time as a doctor then, so I would basically get up at about 4:45, 5:00 in the morning, and I would write the novel for about three hours and then get ready and leave, see my patients at 8:45, and then I would do it again the next day. But it became a routine for me. I learned a lot about myself that year. I learned a lot about what it takes to write a novel. There is a romantic notion to writing a novel, especially when you are starting it. You are embarking on this incredibly exciting journey, and you’re going to write your first novel, you’re going to write a book. Until you’re about 50 pages into it, and that romance wears off, and then you’re left with a very stark reality of having to write the rest of this thing. And that’s where a lot of novels die. A lot of 50-page unfinished novels are sitting in a lot of drawers across this country. Well, what it takes at that point is discipline, and it really comes down to that.

You have to be more stubborn than the manuscript, and you have to punch in and punch out every day, regardless of whether it’s going well, regardless of whether it’s going badly. And I said to myself, “I’m going to wake up every day at 5:00, and I’m going to keep wrestling this thing until I’ve got it down, and I’m going to win this thing.” And that’s pretty much what it took both times to write my novels. It’s largely an act of perseverance and outlasting the manuscript who really, really wants to, wants to defeat you. The story really wants to defeat you, and you just have to be more mulish than the story. And that’s what it came down to. I’m being slightly facetious, but it really is, you really can’t give up. And of course, at one point the story, something grabs, took hold of me, and at that point, there was no choice left. I was so taken with the story, and so swept up in that world, that I had to write it. At that point, there was no choice. I really had to finish it.

It must have taken a lot of support from your wife to work at a very demanding full-time job and give three or four hours to writing every day.

Khaled Hosseini: Well, but she was snoring away while I was writing. I was getting up at 5:00. You know, she was — she indulged me with it. I mean, at that point, she knew very little that I really loved to write. She saw it as something that I’m doing on the side, and it really wasn’t until I gave her a draft of it that she was — she looked at me in a different way. She looked at me like, “Oh, so there is this other person that I’ve been living with for years. I didn’t know this side of you. I didn’t know this dimension of you.” And then simultaneously, I found another dimension in her in that I discovered that she’s the greatest editor I’ve ever met. And she started editing my manuscript, and she’s one of these incredibly gifted readers. She’s not a writer herself, but she’s a very astute, smart reader. And she now edits everything I write, and she’s my first editor at home. I don’t send anything out until she reads it.

What does she do for a living?

Khaled Hosseini: Well, at the time she was an attorney. When we married, she started law school and she was an attorney. And really, I have to credit her for getting The Kite Runner published, because when I was writing The Kite Runner, I was about two-thirds of the way through, September 11th happened. And at that point, I stopped writing the book, and especially when politically it became obvious that there was going to be a war in Afghanistan and that — not the Afghans, but certainly the regime of Afghanistan, the Taliban had hosted the people who perpetrated the attacks. I said to Roya, I said, “Nobody is going to want to hear from me now, nobody wants to read this book.” And you know, it also felt like I was, to submit the book at that point, it felt like the timing was too good. It felt opportunistic.

It was some sort of defense of your people or something like that?

Khaled Hosseini: It felt more like I was capitalizing on something that was suddenly of intense interest, and just because it was in the news and everybody was talking about it, and then here comes a guy with a book — you know. I said to Roya, I said that, “Good timing is a good thing, but this feels like I’m capitalizing on this.” And besides, quite misguidedly, I thought, “We’re the pariah now and nobody wants to benefit me by reading my book. I’m from the country that…” But it was really kind of naive and really short-changing people and not giving them enough credit. People were, as I said, people have been incredibly kind and gracious. So Roya said, “No, you’re being really silly. You have to finish this book. A: You have to go back to writing it, and B: you have to submit it, because it will help readers appreciate a different side of Afghanistan that they are not getting, especially now. All that we are hearing is Taliban, Bin Laden, war, Taliban, Bin Laden, war, Taliban, Bin Laden, war. And your story is about family. It’s about friendship. It’s about love and forgiveness and very, very human, simple human things. And your book can at least give people a glimpse of something other than the usual things that we hear about Afghanistan.” And so, as I said, she was an attorney, and she made her case, and I listened to her, and I eventually submitted the novel in June of 2002.

And who did you submit it to?

Khaled Hosseini: Well, as I said, I didn’t know anything about what it takes to publish a novel. And so as I wrote the novel, and increasingly it looked like I was going to submit it, as unlikely as that seemed initially, I had to learn how books are published. So I went and bought a book called How to Publish Your First Novel, and I learned through that book that you have to find an agent. So then I went and got a book that is called How to Find an Agent. And then I eventually just sent submissions to agents in New York and got connected with a woman named Elaine Koster in New York, who called me, and I had one of the most amazing, surreal phone conversations of my life with her. She called me at my home — I had absolutely no expectation that anybody would look at this thing, read it, talk to me about it. I fully expected the thing to end up with a slush pile, in a trash bin. She called me and she said, “You’re going to publish your first novel. There is no question in my mind about that. The question is: where?” And I was like completely stunned.

So she had read the manuscript.

Khaled Hosseini: Yeah. She loved it, and she called me, and she said, “If you let me, I will find you a publisher in a matter of days or weeks, and this will get published. And I think it will be a very big success.”

Did you have an introduction to your agent, or did you find her by cold-calling?

Khaled Hosseini: I cold-called a bunch of agents through mail. I just sent them three or four chapters with a query letter and a synopsis, and I said, “Look, I’m a doctor working at Kaiser, but I’ve written this novel. I’m from Afghanistan. Here’s a novel, here’s a story. Call me if you like it.” That was basically the way it worked out. And as I said, I didn’t expect anybody to — in fact, I got rejected more than 30 times before Elaine called me. I still have the manila folders of all of the rejections that I received from agencies. I didn’t take it personally, I knew that you have to have a thick skin, that rejection is part of the game. If I’m going to submit, I have to expect that I’m going to get rejected a whole bunch of times, and hopefully somebody will respond, and that is what happened.

Did you actually get the 30 rejections before she contacted you?

Khaled Hosseini: I had waves of submission, and I started getting lots of rejections, and I would just kind of stubbornly keep submitting to six, seven agents at a time. And I had a nice little collection of rejections by the time she called me. Most of the rejections were very impersonal: “Your book is not right for us. Thank you.” — which led me to believe that they hadn’t read it. Some of them had actually read it, and I remember one rejection was, you know, “We like your book, but we think Afghanistan is passé. We think people don’t want to really hear about Afghanistan, they are sick of it, maybe in a few years if you submit it again.” And it was at that point that I realized what a subjective industry publishing is, and you can’t give up, you can’t just let that get you down and you just have to accept that and move on and keep pushing, so I did and found Elaine. She said that, “Your book is going to be a very, very big success, and the publisher said that.” So I was all geared up for the book the day it comes out, and then the reality, of course, is that when the book is published, it’s just a book in a sea, in an ocean of books. And the odds against it becoming a success are astronomically high. So I feel like for me to be here today speaking to you, and everything that has happened, it’s just been a series of really kind of very, very unlikely miracles.

The short story writer Ann Beattie says she had 22 stories rejected by The New Yorker before they finally accepted one.

Khaled Hosseini: The New Yorker, Esquire and Atlantic Monthly, and I have those three rejections as well. Esquire had actually read it, and I got a nice handwritten — an actual nice handwritten response that they had actually read it. But, you know, you can’t take it personally.

Can you imagine how chagrined all of those publishers are now? When did you and Elaine realize that you had a hit on your hands with The Kite Runner?

Khaled Hosseini: Not for a long time. You know, the novel was published in June of ’03, and I couldn’t pay people to read it. I mean, it didn’t come with a big marketing campaign. It was fairly modest, went to a handful of cities.

Who published it?

Khaled Hosseini: River Head, over at Penguin. They did some muscle behind it, but we didn’t have the benefit of an Oprah or The Today Show or a TV appearance, anything of that magnitude. It was mainly doing local radio and a couple of NPR appearances.

It was very kind of sobering to walk into a bookstore at a book reading and see three people or two people, especially when you are in your mind, you think, “Oh, it’s going to be successful,” and it really wasn’t. It took it about 15 months before it finally took off. In fact, it never took off in hard cover. And it really wasn’t until about two or three months into its paperback publication that suddenly — but all, the whole time that I was under the impression that nobody was reading it, people were reading it, but they were reading it in small numbers and telling their friends to read it. So the word of mouth was building throughout that whole year so that you reached that tipping point about a year later, and when it came out in paperback, suddenly it kind of became this phenomenon. And then the next thing I knew, I was going to convention centers, and there was like a thousand people. Or going to the TV, and I was seeing people at the airport reading it.

Did you quit your job right away after your book was published?

It was really, really stunning to see suddenly this book that I thought was going — and I kept practicing medicine. I mean, when my book was published, I took two weeks of vacation from work, I went on a book tour, came back and resumed my normal life of seeing patients. And that went on for a year and a half, even after the book became a New York Times bestseller. After it became big, I tried to continue practicing. And I did until December of ’04, and then it became unmanageable. The book really needed its own career. My travel demands and my speaking engagements, everything became — I had to — and medicine is not the kind of thing you can do part-time, really half-heartedly. You owe it to your patients to be available all of the time and to be there and I felt like this is doing a disservice to my patients if I stay. So at that point, I said, “You know, I can’t do both anymore. I’m going to go and write full-time and take a year off.” So I went on a sabbatical at that time.

From Kaiser?

Khaled Hosseini: I went on a sabbatical from Kaiser. I thought it was going to be for a year. By then I had started writing my second novel, and I really took a year to write my second novel. A year later I hadn’t finished my second level, and I decided to take another year, but decided, “You can have one year. You have to resign after a year, so I did.” But they left the door open for me and said anytime I want to come back, we would love to have you. But it is starting to look pretty small in the rearview mirror for me, and it looks like the writing, which I used to kind of facetiously call a gig, has just turned into a career for me.

Did your patients read the novel?

Khaled Hosseini: Yeah. In fact, towards the end of it, by the time I left Kaiser, I began to notice that a lot of my patients were making social visits, and that they were coming in, got some minor thing wrong with them, but they were really coming in to get the book signed. Or Christmas was around the corner, and they had brought like six or seven copies, and they wanted to sign to Uncle Joe. It was really sweet and endearing, but I started to — this is what I went to med school for? And so at that point, that made my decision to leave a little easier.

That’s pretty funny.

Khaled Hosseini: They would come in with legitimate problems, but they would spend ten of the 15 or 20 minutes talking about my book and then five minutes left to talk about their heart disease. So I felt like I was kind of hurting my patient encounter.

The Kite Runner is such a vivid portrayal of Afghanistan. How much of it is autobiographical, how much of it is fiction?

Khaled Hosseini: Like any other first time novelist who writes a novel in the first person, those first books, as you know, tend to be a little more autobiographical than the subsequent ones. It’s not a memoir by any stretch of imagination, although I have surprisingly a hard time convincing some of my readers of that. You know, there are some parallels within my life and the life of the boy in The Kite Runner. I grew up in Kabul in the same era, I went to the same school, we both were kind of precocious writers, we both love film, loved those early Westerns of the ’60s and ’70s. We love poetry and reading and writing from a young age, both me and this character. And both of us left Afghanistan and became political refugees in the U.S., and probably the sections in the book that resemble my life more than any other are the ones in the Bay Area, where Amir and his father are selling the goods at the flea market and socializing with other Afghans who left Afghanistan. I did that with my father. We would go to the flea market to sell some junk, and we just socialized with other Afghans. So there is quite a bit of me in the book. The story line itself, what happens between the boys and the fallout from that, that just — that is all imagination.

Did you have a sense of guilt about being raised in a family of great privilege economically when there were people nearby who were so much worse off? It seems like the emotion of guilt is very powerful in that book.

Khaled Hosseini: Yeah, it is. I don’t want to say that I was an exceptionally observant child, but I think to some level, I must have been. I must have had some sense of awareness about my life and some ability to put it in context for myself. Because I remember when I was a kid in Kabul writing stories, and all those stories, now that I think about them, and I don’t remember them all, but I remember some of them, had this idea of social class. They had this theme of the clash between the different social classes and the kind of inequities that exist in the world. Because when you grow up in a Third World country, you know, poverty and affluence are juxtaposed. It’s literally next door — you don’t have to go to another zip code. It’s right there when you walk out in the street, and there are beggars and so on and so forth. So it becomes part of your life, and you can either not, just not reflect on it, but I must have, because I remember my stories always had to do with these things. There was always some guy who came from a very affluent background and some person who came from a much less privileged background, and their lives collided in some way, and tragedy would ensue inevitably. I mean, sort of a recurring theme in my stories, and The Kite Runner is very similar to that. So I think I must have had that, and maybe you call it guilt or it’s quite possibly that.

Certainly there was a sense of survivor’s guilt about my life in the U.S. when I went back to Kabul in ’03 finally. Went back there as a 38-year-old doctor, and I had left an 11-year-old boy. And I saw what my life could have been. I saw these Afghans were living there, and I realized the reason I’m not there and my life is — I have a 401K at home, and I have a home with children and everything, is sheer dumb luck. That’s really all it is. So there is a sense of you that questions whether you made the most of what you were given and whether you deserve to be where you are. And that’s a kind of guilt that I think a lot of people that are refugees from states that are in conflict have. And then you go through a phase where you kind of get over that, and you think, “Well, how do I turn that into something a little bit more positive, more productive? How do I turn that — instead of turning you inside, how do you turn it back out and externalize and do something useful with it? And so I reached that stage as well.” And part of the reason why that happened is because people began contacting me because my books became quite well read, and I had credible organizations that wanted to work with me and give me an opportunity. To use a tired old phrase: “to give back” — and to kind of segue my literary success into something, hopefully a little bit more meaningful.

What response did you get from Afghans in exile to The Kite Runner?

Khaled Hosseini: Largely positive, although I should footnote that by saying that people who hate a book usually don’t take the time to write the author. Most of the letters that authors receive are from fan letters. I got some hate letters and that sort of thing, too, but by and large, it was very positive. When people saw their own lives on the pages of that book, they identified with the characters and what happened to them, and there was also a sense of pride and an improvement in self-esteem. Afghanistan has been associated with so many horrible things — war and famine and terrorism and these things — that to have something be associated, even in a modest way, with something that gets more positive recognition, for a lot of people that is a source of self-esteem and a source of pride, of community. So I got a lot of letters for that theme as well. That said, I also received letters, in my estimation the minority of people, but certainly a distinct minority in the community, who feel that the book is harmful. That the book talks about things that shouldn’t be talked about and that it paints a negative image of Afghans and that it destroys the image of Afghanistan. In fact, one person went so far as to say that I had managed to do what the Soviets could never do, which was destroy the image of Afghanistan, which I felt, even by Afghan standards, was really over the top. But my response to those things, and I understand that criticism, and this was the reason why The Kite Runner, the film, was not released in Kabul. I understand that.

These issues of contempt, of rivalry between the ethnicities, for instance, between the Pashtuns and Hazaras, this goes back centuries, and it has very bigger old roots and wounds that have not healed. And this book talks about those things in a very unveiled, open fashion. And for a lot of people, that was a jolt. Things were being said in this book that it would be unimaginable that it would be said publicly within the Afghan community. Lots of people would think it and maybe discuss it privately in their home, but would never blog it, they would never write in the newspaper an op ed or let alone write a book. And so it became — I understand why it’s a subject of controversy, but I feel as a writer that writers, artists, cannot shy away from things merely because it makes people uncomfortable. I don’t feel that that’s a good reason to not write something. In fact, that’s a very good reason to write about things. If things make, if a subject matter makes people uncomfortable, if it touches on those things that people fear, if it touches on those things that are sensitive, then maybe that is what is worth writing about. I don’t think we, as writers, shy away from things that are wreathed in reality and shape a society and not write them out of mere politeness. And so in whatever modest way, I hope that The Kite Runner has opened a useful and productive dialog within my community. And I think, to some extent, it really has.

There was concern for the safety of the young actors who appeared in the film version of The Kite Runner. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

Khaled Hosseini: This was less than a year ago. This was about six or seven months ago. A lot of the concern came from the father of one of the children who feared that something might happen were his family to stay. And I don’t think it was entirely unreasonable. It is imaginable that people would do something foolish and drastic. So I think the studio, and I applaud them for this decision, because it went really against commercial grain, delayed the release of the film six weeks, which may have hurt the film commercially, and waited until the boys were out of Afghanistan and in a place of safety before releasing the film. So the children were removed to the United Arab Emirates, and nothing really happened. I mean, the film was released, the revolts and the demonstrations and the violence, the doom and gloom that everybody had predicted never materialized. The boys and their families were never threatened. They were never attacked. I spoke to one of the boys a couple of months ago, and they are doing well. They are in private school, and the parents have jobs. They have a home of their own now and are quite happy.

Did you participate in making the film?

Khaled Hosseini: As a consultant. I didn’t really want to be that involved because I felt, I don’t know that much about film, and I don’t want to become one of those people that have worn out their welcome and be an intrusive, an annoying presence. And so I said, “Look, I’m here. If you need me, you can contact me.” And so they did. So I became pretty good friends with the filmmakers, the director, some of the stars and the producers as well. And you know, I chimed in when they needed help. For instance, we decided together on the location, after we looked at hundreds of pictures, of where this film should be shot. Kabul was not an option, unfortunately.

Why not?

Khaled Hosseini: For a variety of reasons. There is the issue of security, and also a film production is like a moving village, and you really need an existing infrastructure and an existing film industry locally to support it. And that just does not exist in Afghanistan today. So we saw pictures of Western China, Kashgar, and I was stunned at how reminiscent it was of Afghanistan architecturally, geographically, ethnically. So they shot the film in Western China. I took my father on the set, and he was so amazed at how much it reminded him of Kabul. And I chimed in on issues about clothing, about language, wherever they needed help.

How did you feel about the film when you saw it?

Khaled Hosseini: Oh, the first time I saw it, it was so hard for me, because I saw it at a special screening with the studio, and all of the studio people were there. The director was there, and I felt like all of the eyes of the theater were on me because — “Is he going to like the film or not?” So I really had to see it a second time, and I saw it a second time, and I liked it quite a bit. You know, as the writer of the book, there are always things — they say, “But I wrote this, and it’s not in the movie” or “You changed that.” But I understood film to be a completely different medium, and I didn’t have expectations that everything I wrote on paper would be on the film. Otherwise, you would be talking about an eight-hour miniseries. So it was a two-hour film, and you have to live within those confines. That said, for me, I was very proud of the film in two ways. One, I was really proud of the children in the film, particularly since they were amateur actors. Not only were they amateur actors, they had never been to a movie theater in their whole life. The scene where they are watching the Western in the movie theater, and the movie, that one, when we were shooting that scene in China, the boys told me, “You know, this is our first time in a movie theater.” And the irony for me that they were acting in a Hollywood production before they had actually been inside a movie theater was — it said so much about the lives that those kids have and what Afghanistan is today, to me. And secondly, for me, the film is a positive step forward for Hollywood that I think has a very checkered past in dealing with that region of the world and its depiction of the people who inhabit the Middle East. Not that Afghanistan is strictly Middle East, but that region of the world. Usually those films center around political violence, terrorism, things of that nature, and this was a film largely about family, about friendship, about personal guilt and betrayal and redemption, regret. Very, very human things. And yes, the characters in the film were Muslim, but they weren’t in the film because they were Muslims. Their faith was incidental to that. And I think that is a really good, positive development.

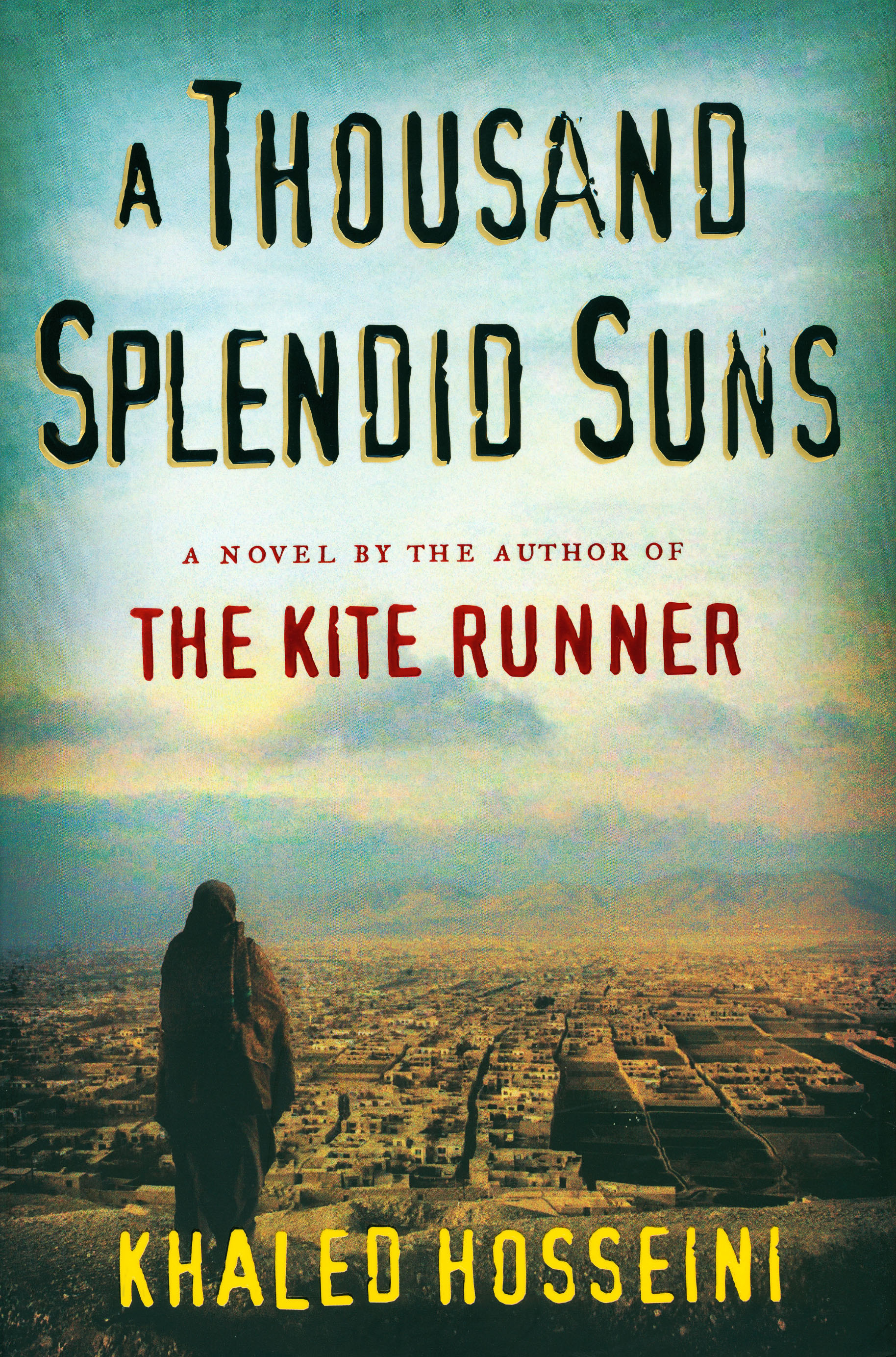

Let’s turn to A Thousand Splendid Suns. You portray the Soviet invasion and the subsequent civil war so vividly. You weren’t in Afghanistan when these events took place, but you write about it with such vivid detail and passion and pain. Where did that come from?

Khaled Hosseini: Largely from my conversations with people on the streets of Kabul. In the spring of ’03, before The Kite Runner was published, but after it was done, so in that period between the two, I went to Kabul for the first time in 27 years and spent two weeks talking to people. Now at that time, I didn’t go there with the purpose of research. I mean, it was really there for me to reconnect, see the city and fulfill some kind of nostalgic longing that I have had for years. And three, to understand for myself what really happened, how it impacted people and how people coped.

One thing about Afghans is they are incredibly generous with their storytelling, and so when I was walking the streets of Kabul, you can literally walk to any shop and stop somebody in the middle of whatever they are doing and say, “So who are you? Tell me your story.” And they will stop what they are doing, and they will talk to you. And chances are, they will invite you to dinner afterwards. And so I learned a lot about — I knew the facts, I knew the figures, I knew the statistics and so on and so forth, but what it missed, what it lacked for me, my understanding, was a human dimension. It was the, “How did people survive and what was it like for them?” And so I spoke to hotel doormen, taxi drivers, people who sold baked beans on the side of the street, people who worked in clothing stores, women who worked in schools and in hospitals. And I got their stories from them, just so I could understand for myself personally. So a lot of the details, the incidents that are in that book come almost directly from things that I heard or saw in Kabul. For instance, there is a scene in the book where this young woman who is delivering a baby has to have a C-section. Unfortunately, the hospital has no anesthetic, and so she has a C-section without anesthetic.

I have visited a hospital in Kabul, and I was talking to a neurosurgeon, and he told me that when the mujahideen were fighting over Kabul, and on particularly violent days, the hospital waiting room would be packed with people who were badly injured. Some of them needed amputations and so on, and the hospital was already running on a threadbare kind of supply and had almost no supplies anyway. He would frequently have to perform amputations, C-sections, appendectomies, all sorts of things without the benefit of anesthesia. And so that’s the kind of indelible, vivid detail that you can’t forget, and I didn’t begin writing this book until a year after that visit. But when I sat down to write it, a lot of those stories came rushing back. And they coalesced together and formed for me a world where I could plant these characters and navigate them.

Sometimes there is a delicate balance between portraying violence and brutality, and exploiting the suffering of others in some way. Were you at all conscious of that?

Khaled Hosseini: Yeah, I think the charge is legitimate if those things are being written about merely for the sake of shocking, or for the sake of the cringe factor, and they are not done in a greater context of creating an understanding, of painting a picture of a world in which people live that they actually suffered. Of creating, hopefully, a sense of enlightenment and illumination about the truths of that place and that time. I was quite sensitive to that, and in fact, there are things that I saw and heard in Kabul which I decided not to write about, because to me, they were so harrowing that there was no way of writing about them. You would have to be a far more skilled writer than I am to pull that off. So I stayed within the confines I think that would help me create this world for these characters and lend a sense of authenticity.

I went into this book, as opposed to The Kite Runner, with a slightly more sense of mission. And that The Kite Runner was really about, “Wow, I’ve got this little short story. Can I write a book? Can I make that novel?” At least that is how it started; it became something else. But the second book, I had decided already that I was going to write a book about women, and I wanted this book to be a fictional account, however narrow in its aim of what happened to these women in Afghanistan. So many people suffered in Afghanistan over the last three decades, but it’s hard for me to find a group that has suffered more than women. Because they suffered the same things as the men did in terms of the violence and the indiscriminate bombings and so on, but they also had to suffer from gender-based abuse. So here are these stories of girls —12, 13, 14 years old — being forced into marriage with militia commanders or being abducted and sold abroad. Or girls that were being raped as a means of punishing a family that had maybe supported the rival faction, girls being sold as prostitutes and so on. It was so harrowing, I felt that this was a really important story. It’s a relevant story, and it’s a story that is still developing today and that has not resolved. We still have many of those problems in Afghanistan today, even though it doesn’t get as much press. Those problems are still very real today. And it had never been done in fiction before, at least not to my knowledge, and I felt like that was something very natural for me, and I felt a personal sense of passion to tell that story. But I didn’t want to just write about those things. As a novelist, I need character, I need story, I need something to sit me at the computer, and I want to find out for myself a mystery about somebody. And it really wasn’t until the characters of Mariam and Laila began to form in that fog that I was able to sit down and actually write this.

The form of A Thousand Splendid Suns is interesting, because it switches back and forth between the heads of these two women. How did you decide on that form?

Khaled Hosseini: The structure of this book took a lot of work, because I knew I wanted to tell the story of two women who were separated by quite a bit of age. And I felt the flip-flop between the two was gimmicky and distractive, so I decided that at some point, after trying various different forms, including a kind of an unfortunate flirting with an epistolary form, that I would tell the story of Mariam, stop, and then go to Laila, stop, and then tell their story together. And so the book kind of unfolded naturally into three different sections with a short epilogue at the end.

When you said epistolary form, do you mean you thought about writing the whole novel in letters?

Khaled Hosseini: Well, it was semi-epistolary because I felt one way out of this would be to meet Laila through the letters, a diary that she was keeping of letters that she was writing, and her section would be composed entirely of letters. And I gave it a try, and it just didn’t work at all. But for me, writing is always like that.

I know that I’m going to do things that aren’t going to work, but I have to do them to find out for myself. I have to go down those blind alleys, whack my nose against the wall, turn around, walk out, go a different way, bang my head against another wall. I mean, there is no going directly to where you want to be; you really have to go through all of those other turns to get to where you want to be. At least for me, it has always been that way. The really gifted, the really great writers, I’m sure you have interviewed many of them, they have a clear path. You know, there is no detour, or at least that is what I imagine. But for me, I have to go through various drafts. I mean, I wrote probably five or six drafts of this book, some of them complete drafts. And so eventually this structure of seeing Mariam from childhood to womanhood and picking up Laila from childhood to womanhood, that felt the most natural format for me.

It was a daring choice to have the connection be that they are married to the same man at the same time.

Khaled Hosseini: I saw this book as a story in which there is a smaller drama and a greater drama. There’s the human drama of what is going on in the household, and it comes with its own tension, its own violence, its own rivalries and camps and factions, really. And then there’s the bigger story of what’s happening outside the doors of that house, the rivalry between the different factions, and the war that is unfolding and its effects on the household. So it was kind of a bit of a juggling act to balance what is going on in the interpersonal human stuff with the political events outside, which in many ways, impact those interpersonal relationships. That juggling act took a bit — especially there is a natural tendency to want to be an historian, an amateur historian and talk more about the political stuff, and that is very seductive to do. But ultimately, a novel is not about — it is really about the characters and their emotions and so on, so I would have to restrain myself a little bit.

In your novel, we read about the proclamations that the Taliban made, restricting women in your country. Where does that contempt or fear come from? What was it about women working professionally or showing their faces that was so threatening to them?

Khaled Hosseini: The Taliban’s proclamations have a root in the history in Afghanistan for centuries. Afghanistan is largely a rural country that is religious and uneducated. That’s a sad truth. In many parts of Afghanistan, at least in the tribal and Pashtun regions of Afghanistan, the way the Taliban perceived the role of women in society is pretty much the way women have been perceived for a long time. In that tribal code of life, it is considered dishonorable for your wife, your sister, to be seen in public by the eyes of a stranger, to be seen alone, to be seen that she is speaking with a stranger. It is considered an insult to the family. There is also, in that tribal code, an inherent distrust of women. They are seen as somehow immature, more immature than men when it comes to social conduct, sexual conduct. And so not only they’re the center of honor of the tribe and have to be protected from outside influences, but they also have to be controlled. And so the practice of purdah, or living in seclusion, comes from that.

So largely, if you go to a village outside of Kandahar, for instance, a very deep tribal Pashtun region, you are very unlikely to see a woman on the street, and if she is seen on the street, she is probably fully draped and is walking with a male relative to whom she could not legally be married. So that is the code.

The thing that was really remarkable about the Taliban was that it took something that is a tribal custom in some parts of Afghanistan and turned it into national law and imposed it on the entire populace at large. And that was a shock to the system for urban professional women in Kabul who had grown up working in universities, as doctors, as lawyers, as teachers. And suddenly they had to behave like an illiterate, uneducated young woman from a village in the middle of the desert outside of Kandahar. Suddenly they had to be indoors all of the time, couldn’t work, couldn’t get an education, had to be fully covered when they go outside, and the litany of things that have now become very, very familiar to the public. That was the remarkable thing about what the Taliban did, and the hardship that it imposed on women who were not used to that was enormous.

Where do things stand today, in the summer of 2008? Do you have a sense of optimism about Afghanistan?

Khaled Hosseini: If you’re optimistic, you have to be quite sober about your optimism or you look foolish. You have to admit to things. One is that some good things have happened in Afghanistan and not lose sight of that. It’s important to remember that the country is in a better place than it was seven, eight years ago. There is more personal freedom, the economy is better. Some will say that it’s largely because of drug trade, but it is better.

Are women going to school?

Khaled Hosseini: Women, at least in urban regions like Kabul, are back in the workforce and some of the infrastructure has been rebuilt. So those are positive things. Education actually is one of the success stories of the regime. On the other hand, some things either have not changed at all or have got worse. Security certainly has gotten worse since the last time I was there in 2003. We have a full-blown insurgency in the south and in the east. The suicide bombs, which were unheard of in Afghanistan in the two decades before, have suddenly become commonplace. You have a flourishing opium trade which is criminalizing the economy and supporting the insurgency. And you still have, you have a populace that is growing disillusioned with the regime and Kabul and with the West, in that they are not seeing the promises that were made, they are not seeing the fruition of those promises, seeing that those promises have been kept. They are not seeing enough difference in their day-to-day life. They are still jobless, homeless, have no access to water, schools, doctors — not everybody, but a significant portion of people feel that way.

I know that from visiting Kabul this past September, and actually going outside of Kabul to Northern Afghanistan, and talking with people who come back from Iran and Pakistan and have tried to resettle in Afghanistan, and the enormous challenges they face in Afghanistan and the little support they feel they get from the government. It should also be remembered that that government is still in its healing stages. It is trying to rebuild a country that has unraveled for the last 30 years and is recovering from a massive catastrophe. Even acknowledging that, though, I think most people felt that Afghanistan would be, seven years later, in a different place than it is today. There is a frustration with the pace of reconstruction and the pace at which people are seeing their lives change.

How is the U.S. viewed in Afghanistan today?

Khaled Hosseini: Still in a positive way. There is still, I think, a reasonable amount of goodwill for the U.S. They were never perceived in a negative way. I think Afghans are a sovereign people, they have a long history of not welcoming invaders. But I don’t think the States, the U.S., or NATO are seen as invaders largely. I think what preceded the arrival of the Western forces was so horrible, namely the commanders, followed by the Taliban, that the West is seen as, at least hopefully an antidote to those ills. So people are still, have goodwill for the U.S. I think when you talk to people, there is actually a fear that the West will pack its bags and leave. They feel, not that there is a great love for having foreign troops on their land, but because they feel that if they were to do that, it is all too easy to imagine that the country would slide right back and be back into chaos and be, once again, a playground for commanders and drug traders and extremists, which you have to agree with. And so there is still quite a bit of goodwill, but I think the danger is that we have to — we being the West — and I say this purely as a lay person, I don’t think there is a military solution in Afghanistan. I think the military — I think the solution comes not only from military, but it comes really, I know a tired clichÈ, of winning the hearts and minds of the people. It’s a race between us and the Taliban to convince people which is better for them and which will keep their promises and which understands them better. And I’m not sure that that’s a battle that we are winning right now.

We spoke to President Hamid Karzai shortly before the last elections.

Khaled Hosseini: Five years later, you have to say that, fairly or unfairly, that his image has eroded to some extent. I met him as well last September.

He was very convincing in his optimism that things could get better fast. Five years later, it doesn’t look like things have gotten better that fast.

Khaled Hosseini: No, they haven’t. To give an analogy, the rebuilding of Afghanistan is not a hundred meter dash, it’s a marathon. And we have to be ready for long-term commitment. When you go to these conferences about Afghanistan, those three words come up again and again and again. It’s natural to want to see results fast, and I also think things could be better than they are today. There’s definitely some legitimacy to the concerns that people have, but I think we also have to wait. This is a country in which every meaningful institution was ravaged, and that saw massive human displacement. Millions of people live as refugees abroad, and in which there was a destruction of an already threadbare infrastructure. This country has to be raised from the ashes, basically. Is it reasonable to expect that in six or seven years it would be great? I think any success in Afghanistan has to be measured in decades. That’s probably what we are looking at.

Your poor country has had such a history of invasions and massacres. What is the draw for other countries? Is it geographical?

Khaled Hosseini: Afghanistan’s great draw is its position. As Afghans call Afghanistan the heart of Asia, it’s always been a gateway, a passage, throughout history, for different empires to march through. Peter the Great always had dreams of the waters of the Indian Ocean, and for that, he needed Afghanistan. And of course, the British Empire wanted to prevent that, so they had a stake in Afghanistan, and it was the genesis of the Great Game in the 19th century. For the Soviet Union to invade Afghanistan in the late ’70s, there is a lot of debate over why exactly they did that. By no stretch of the imagination am I an expert, but one school of thought is that the situation had gotten out of hand in Afghanistan, that the puppet regime, the communist puppet regime was losing control of the country, and the Soviets invaded really to take matters into their own hands. But Afghanistan’s draw has always been its position, and it’s a passageway.

The success of your first two novels has been astonishing, but there were a few negative reviews as well. How do you react to criticism of your writing?

Khaled Hosseini: You have to have a very thick skin, and also to not dismiss somebody who is critical of your work right off the bat. It may be that they have a legitimate point about something. If it’s personal — it’s rarely personal, but if it’s just done to be clever, to be glib, that is one thing. But I find that most people, most critics don’t write that way, and whatever objection they have, whether I agree with them or disagree with them, comes from a viewpoint that has coherently been thought about. It’s never easy to see unkind things said about your writing, but I actually have benefited from largely good reviews in both of my books. And certainly you can’t have uniformly great reviews, but the reviews on both of my books have been great. And the fortunate thing for me is that the reviews for my second book were actually better than The Kite Runner, and that was rewarding for me, because I felt like as a writer, I definitely had grown, I had become a better writer the second time around than I was when I wrote The Kite Runner. But you have to take negative criticism of your writing with a grain of salt. It’s a privilege to be published, and that comes, that is part of the game.

One of the challenges of your second novel is writing largely from the point of view of a woman, something that writing teachers frown upon in college. Could you tell us about the challenge of writing from a woman’s point of view?

Khaled Hosseini: Had I known that college teachers frown upon that, I might have been less enthusiastic about doing it. I think part of my good fortune is that I trained in the sciences, so I have never been in those conferences. I never sat in those classrooms where you are told what is allowed and what is not. So I said I want to write this story, and it’s going to be about a woman, and then I realized it’s about two women. And I called my agent before I began writing the book, and I told her, “Here’s what I think the book is,” and there was a long pause at the other end of the line, and she goes, “Well, you have your work cut out for you.” I said that I thought I would be okay, and then I began actually writing it and realized what I had taken on. This novel took me almost three years to write. The Kite Runner took me a year, and that was with working full-time. I wrote this novel largely away from medicine. I had already quit my career and yet it took longer.

I struggled with the notion that I’m writing from a woman’s perspective, and the last thing I want is to sound like the reader to read it and say, “Oh, yeah, this is a guy imagining what it’s like.” You know, I became borderline obsessed with the idea of capturing that voice, definitely, of writing with the understanding that women live in a slightly different emotional arena than men do, and that they perceive the world in a different fashion than men do. And that somehow I have to find that. I have to slip my feet into those shoes and live in that skin. And until I do, it’s never going to work. And of course, the harder I tried, the worse the writing and the more self-conscious and stilted and contrived it came across. Eventually, all of the solutions that I’ve ever found in writing have been very simple, but I have to go through all of those blind valleys to get to it. And of course, with this one, I finally gave up on this and said, “Look, I’m just not going to worry about it, I’m just going to write these people as people, as human beings, and just focus on what it is that they fear, what it is that they hope, how were they disappointed by life, what are their illusions, their disillusions. You know, what way are they deluding themselves, in what way are they honorable or less than honorable. Let’s just figure those things out and just write them as people and not worry about whether it’s a man or a woman.” And of course when I did that, suddenly I began to notice that my voice was fading away and that these women, these characters, were starting to speak for themselves. And that was, for me, in the writing of this book, really a watershed moment. I should not think of these characters as Afghan women in italics, but rather are just people. Write them and hopefully it comes across as genuine. And I haven’t had too many complaints about the voice and so on, and so I feel, personally I feel pretty pleased with it, and I’m glad to see that a lot of people agree.

Does having a medical background help you in any way as a novelist?

Khaled Hosseini: To some extent. I never really thought about it that way. I think writers have the ability to kind of get out of their own skin for a while and imagine what it would be like to live in somebody else’s skin. And for me, there were periods where I imagined what it would be like to be wearing the burka and to see the world through that grid. Okay, so imagine you are standing on that street corner with five or six kids to feed and that’s the life you have. What is your next move, what do you feel, what are you thinking? There is some element of that, and maybe writers have slightly a better ability of doing that than people who aren’t writers. I don’t know, but once I made that leap that I discussed, it seemed far more natural for me. I had also the benefit of talking to my mom and my wife and consulting them now and then on things, and they were very helpful, they were very helpful. But I met women in Afghanistan and I heard their stories. I mean, you can’t walk up to a woman in a burka on a street corner and talk to her. I don’t want to give that image, but I spoke to women who work for NGOs, who were taking care of those women who are fully covered and who won’t talk to men. You know, and I heard a lot about their lives, about what they go through and the hardships and the challenges and what is the hope. And what I found is, by and large, the things that they want were very modest in scope, basically a roof for their kids and water. And so I always keep honing back on that and to come back to the idea. And these characters, these women Mariam and Laila, were not based on any individuals that I met in Kabul, but rather they are created out of that collective experience of those collective voices that I heard during that trip.

It takes tenacity to survive a bad first draft. If you feel like you have to write Nobel Prize-winning prose when you begin, it can be paralyzing. How do you find the patience to go through all of those drafts?

Khaled Hosseini: Writing a book, as I said earlier, is largely an act of perseverance, and you have to stick with it. The first draft is very difficult to write, and it’s often quite disappointing. It hardly ever turns out to be what you thought it was, and it usually falls quite short of the ideal in your mind when you began writing it. But what I would say is a first draft is just really a sketch on which you can now add layer and dimension and shade and nuance and color.

So I use the first draft purely as a frame on which to build the actual story. So a lot of my writing is done through rewriting. And I don’t become discouraged by the notion that my first draft is not going to win any prizes or that it’s not going to be — I understand that it’s going to be lousy, but I want all of the essential elements to be there. The heart of the story has to be in that first draft, and then I can use that to create something and discover things about the story. When I wrote, for instance, The Kite Runner, there were a lot of things in that first draft that stayed, but some things in that first draft were tossed, and the transformation in some passages were very dramatic. I wrote an entire draft where the two kids were not brothers, and it really wasn’t until a subsequent draft when I realized that the kids, suddenly the idea came — well, what if the kids are brothers, and that changed the whole tone of the story. And when I rewrote it, writing it with that knowledge, it changed everything. And so you can get discouraged. Writing is largely about rewriting, and I abhor writing the first draft. I love writing subsequent drafts because that’s when I can see the story getting closer and closer to what I intended and what my original hopes for it were.

What other advice would you give young fledgling novelists?

Khaled Hosseini: I have met so many people who say they’ve got a book in them, but they’ve never written a word of it. I think to be a writer, you have to write. You have to write every day, and you have to write whether you feel like it, whether you don’t, and be stubborn. And you also have to read a lot. Read the kinds of things you want to write, read the kinds of things you would never write. I find I learn something from everybody. I would never say I’ve been influenced directly by a given writer, but I feel like I’ve learned something from every writer that I have read. And I read with kind of a different — I read to pay attention to the voice. I pay attention to how they write dialogue. I pay attention to how they resolve conflict, how they form structure, the rhythm of a story. Sometimes with a critical eye, often with an admiring eye with really great writers. And so keep writing and — probably the best advice that I can give is to write for an audience of one, and that is yourself. The minute you start writing for an outside audience, that immediately taints the entire creative process. I wrote both of these books because I was telling myself a story. I really wanted to find out what happens to Amir after he betrays his friend. Why does he go to Afghanistan? What does he find there? I wanted to find out for myself how the relationship between these two women changed. You really have to tell it to yourself, and then when you are done with it, hope that other people will enjoy it, and just shut everybody else out during the writing process and put yourself in a mental bunker.

Do you think that the more you can do that, the more others will respond to it?

Khaled Hosseini: Well, you hope so. Sometimes it doesn’t happen, and I’m sure a day will come when that won’t happen for me, but I’ve been lucky twice now.

What is in your future? Are you working on another novel?

Khaled Hosseini: I hope to be starting on a new novel very soon. I have mentally been working on it for some time and turning ideas over, but hopefully I will start something quite soon. But that’s all I can say.

What do you think of the American Dream? Do you have a conception of that?

Khaled Hosseini: I feel like I’m the poster child for it, whatever that phrase means now. I came here basically penniless, with a suitcase of clothes, a family of nine people. I find myself now having written these books, and even well before the books, I was already a poster child because I had a very successful career as a doctor, I had married a great woman, had healthy children. But certainly, anybody who writes an article about the American Dream today should call me. I feel like I am a good example of it.

Is it about accomplishing something you couldn’t even imagine?

Khaled Hosseini: It’s about discovering what you can be and giving yourself the chance to do it and be open to the possibility that it will actually happen and taking a risk. For me, writing these books, I am taking a chance with them and hoping that it will be perceived the way it eventually was received. I mean, it is a dream, whether it’s an American dream or a personal dream, but for me certainly the entire thing has a dreamlike quality about it, these last five, six years.

Thank you very much.

Khaled Hosseini: My pleasure. Thank you very much.