We knew that the front page was going to be a historical document, it was going to be reproduced in the history books.

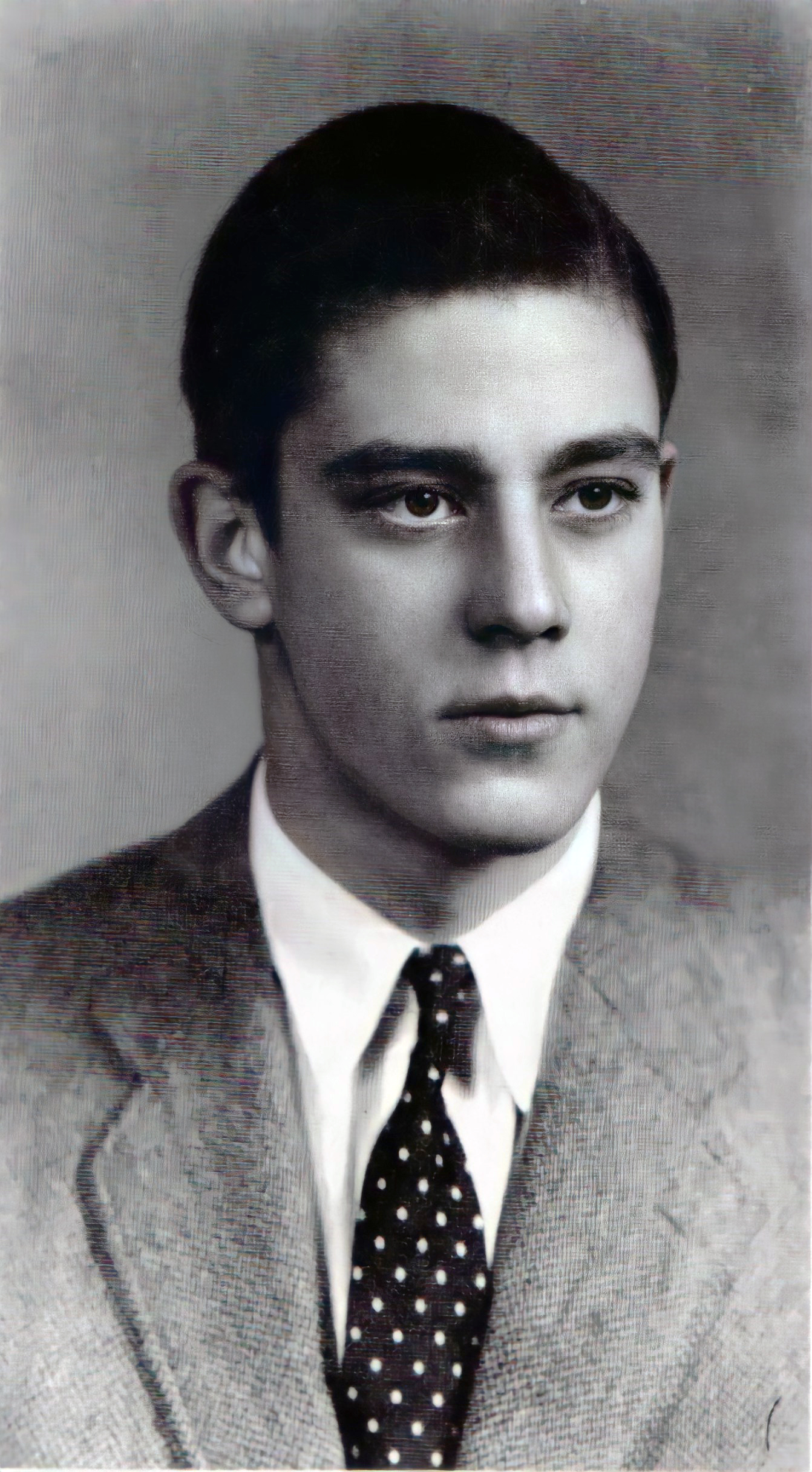

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to a family with deep roots in New England on his father’s side, and European aristocracy on his mother’s. Relatives had achieved prominence in the law, banking, diplomacy and publishing. He spent his first eight years in an atmosphere of wealth and privilege, but his family lost most of their fortune in the 1929 stock market crash. His father, who had been a bank vice president, supported the family by part-time work as a bookkeeper and managing the janitorial staff at the Boston Museum. Young Ben Bradlee’s relatives helped him to attend private schools. He was at St. Mark’s School when he was stricken with polio at age 14. For months he lost the use of his legs, but he exercised rigorously to recover from the disease, and within a year was working as a copy boy for a local newspaper. Like generations of Bradlees before him, he enrolled at Harvard College, where he studied English and Classical Greek and participated in Naval ROTC. On the same day in 1942, he graduated from Harvard and was commissioned as an officer in the United States Navy. He married his college sweetheart, Jean Saltonstall, before departing for active duty. Assigned to naval intelligence, he saw action in some of the most intense battles of the Pacific campaign, including the battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval engagement in history.

After returning from the Pacific, Bradlee worked as a reporter for the New Hampshire Sunday News. In 1948, with the paper failing, and a wife and child to support, he joined The Washington Post as a reporter. His first stint at the Post was a brief one, but he became friendly with the paper’s associate publisher, Philip Graham, son-in-law of the Post’s publisher, Eugene Meyer.

In 1951 Bradlee secured an appointment as press attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. While in Paris, he joined the staff of the U.S. Information and Educational Exchange (USIE), parent organization of the Voice of America radio service. In 1953 he left the USIE to become Paris correspondent for Newsweek magazine. His marriage to Jean Saltonstall ended in divorce, and Bradlee married Antoinette “Tony” Pinchot, an American he met through the U.S. Embassy.

As the Newsweek correspondent, Bradlee interviewed guerrillas who were fighting French rule in Algeria. The French government objected to his contact with the rebels and sought his expulsion from the country. Newsweek brought him back to the United States to serve as the magazine’s Washington correspondent.

Bradlee and his wife, Tony, bought a house in Washington’s Georgetown neighborhood, where they became friendly with their neighbors, U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy and his wife, Jacqueline. Kennedy had graduated two years ahead of Bradlee at Harvard and both had served in the Navy in World War II. Their friendship developed quickly, and the senator became an invaluable source of information for the journalist. Bradlee covered the presidential election of 1960, and after Kennedy’s election, his friendship with the new president enhanced his profile in Washington’s journalism community. When Bradlee learned that Newsweek was for sale, he encouraged his friend Philip Graham to buy it for The Washington Post Company. Graham gave Bradlee shares in the new company’s stock as a finder’s fee and made him the Post’s Washington bureau chief.

The future looked bright for Bradlee, his paper and his country, when he suffered three startling losses in succession. In August 1963, Philip Graham committed suicide after a long struggle with depression. Graham’s widow, Katharine, became the Post’s new publisher. The following November, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The death of the president was followed within a year by the murder of Bradlee’s sister-in-law, Mary Pinchot Meyer, a close friend of the president’s. Many years later, Bradlee admitted that after her death, he and his wife had disposed of a diary in which Meyer had recorded details of an intimate relationship with the president.

In 1965, Bradlee became managing editor of The Washington Post and moved aggressively to expand the newspaper’s national and international coverage. Mrs. Graham came to rely heavily on his direction of the paper, and in 1968 named him to the newly created post of executive editor.

One of the high points of Bradlee’s tenure at the Post came with the discovery of a classified Defense Department study tracing the history of America’s involvement in Vietnam. Daniel Ellsberg, formerly an employee of the State Department and the Department of Defense, was one of the authors of the study. He shared a collection of the Pentagon Papers, as they became known, with Neil Sheehan of The New York Times.

Among other things, the documents disclosed U.S. government complicity in the overthrow and assassination of South Vietnamese President Diem. They revealed that the second Gulf of Tonkin incident — the immediate pretext for America’s direct military involvement — had not taken place as described in official accounts, a fact later confirmed by participants in the alleged incident, including Admiral James Stockdale. The documents also revealed a series of covert U.S. military actions in Laos and Cambodia, as well as North Vietnam. The cumulative effect of the disclosures was to suggest that the government had misled the American people about the rationale for war, its progress, and its likely outcome.

The Nixon administration feared the precedent of allowing classified information to find its way into print. When The New York Times began to report on the content of the papers, the administration obtained a court order enjoining the Times from further disclosures. This was the first instance of a U.S. court imposing prior restraint on a publication. While the Times appealed its case to a higher court, the Post obtained portions of the documents from Ellsberg.

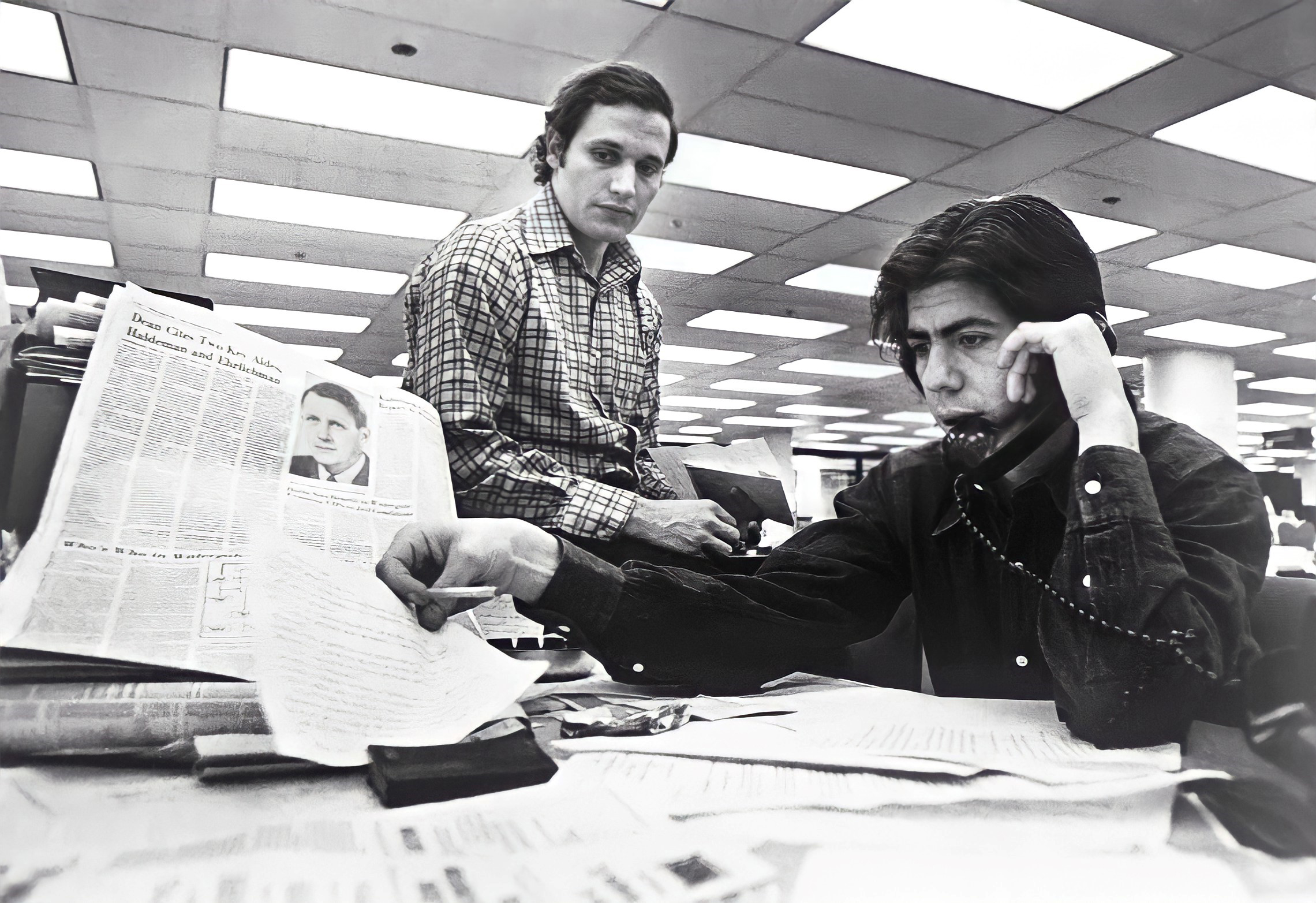

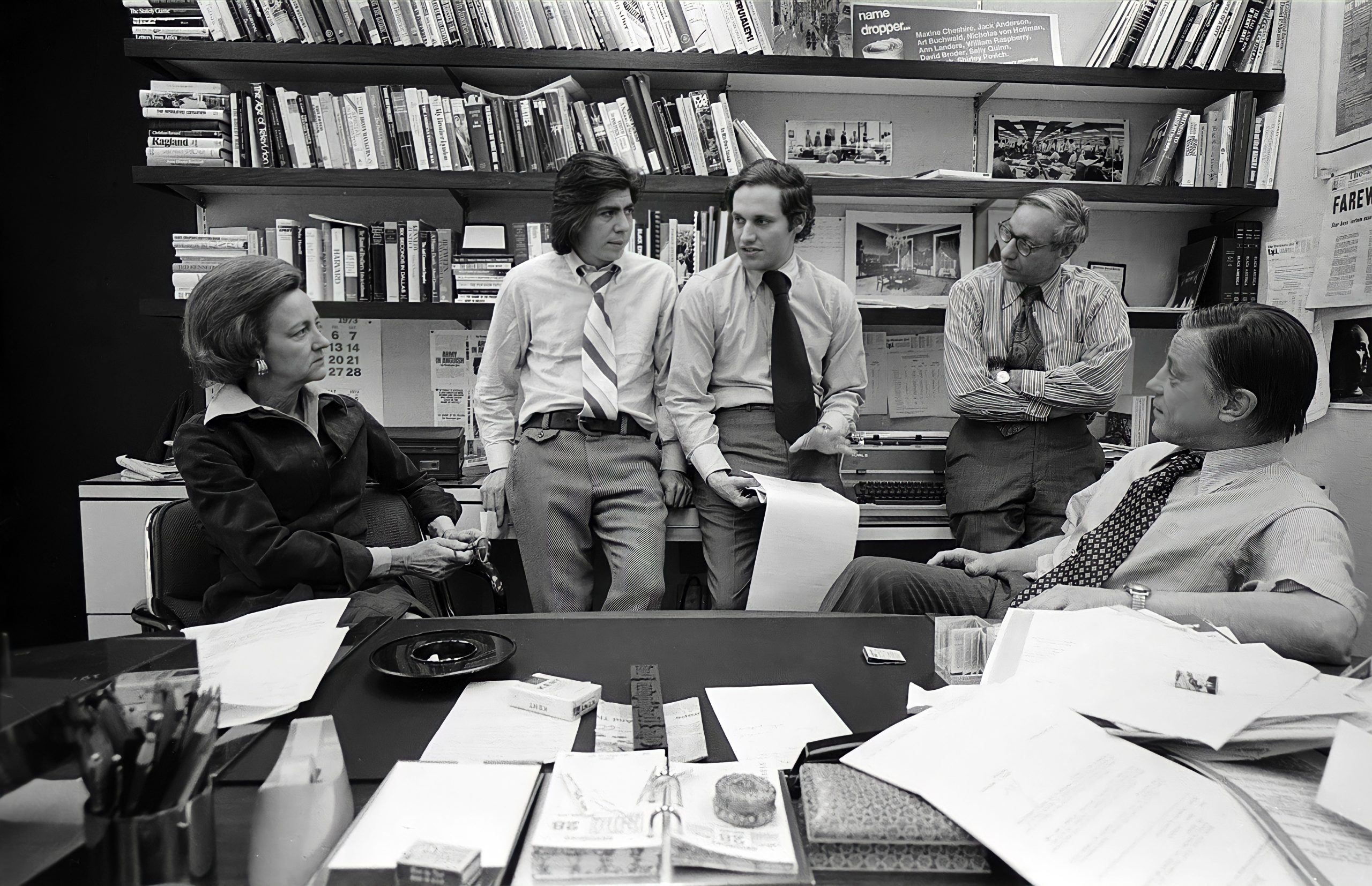

Bradlee and publisher Graham knew they too would face federal legal action if they reported on the contents of the Pentagon Papers. The opportunity came at a difficult time for The Washington Post Company, as it was preparing a public offering of its stock. In addition to the Post newspaper and Newsweek magazine, the company owned a number of radio and television stations, licensed by the federal government, whose licenses could be suspended or revoked. Bradlee and Mrs. Graham decided the public’s interest in learning the truth about the war outweighed any potential risk to themselves or the Post and proceeded with publication. The administration brought a suit against the Post, but the federal court denied the motion, and subsequent appeals ended with the Supreme Court affirming the press’s right to publish information in the public interest without prior restraint. Graham and Bradlee had won a great victory, but the Post’s conflict with the Nixon administration was far from over. Bradlee assigned two young Post reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, to investigate an attempted burglary at the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate office complex. Their investigation quickly discovered a connection between the burglars and a CIA employee working in the White House. In the face of criticism from the president’s side, and skepticism from many in the news media, Bradlee supported his reporters.

After President Nixon won re-election in a historic landslide, Woodward and Bernstein’s reporting led to a Senate investigation and the revelation that the president had authorized the payment of hush money to the burglars — to conceal their relationship with the president’s re-election campaign, and to block the revelation of other covert activities, including an attempt to burglarize the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist. As the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings, the president resigned. The Washington Post had established an international reputation for investigative reporting that would remain unchallenged for many years.

The Pentagon papers and Watergate made Ben Bradlee a public figure on the national stage. He saw himself portrayed by the actor Jason Robards, Jr. in the film All the President’s Men, based on Woodward and Bernstein’s chronicle of the Watergate affair. In 1975, Bradlee published Conversations with Kennedy, a memoir of his friendship with the late president. By the end of the decade, his marriage to Antoinette Pinchot ended and he married Post reporter Sally Quinn.

Bradlee’s tenure as editor of the Post was marred when it was discovered that a 1981 Pulitzer Prize-winning story about a juvenile heroin addict had been fabricated by the reporter, who had also falsified her credentials when she was hired by the paper. Bradlee ordered a full disclosure of the facts and personally apologized to the mayor and the chief of police of Washington, D.C. for the story’s implied criticism of the city’s administration and law enforcement.

In his 26 years at the editor’s desk, Ben Bradlee had doubled the Post’s circulation and made it one of the world’s leading newspapers. He stepped down as executive editor in 1991 and assumed the less demanding position of vice president at large. The shares of Washington Post stock Bradlee received at the time of the Newsweek purchase had made him a wealthy man. In his later years he set out to give much of his money away. He endowed a professorship of Government and the Press at Harvard, raised millions of dollars for the National Children’s Medical Center and served as Chairman of the Historic St. Mary’s City Commission. For many years, Bradlee had maintained a second home in St. Mary’s City, Maryland, the state’s oldest European settlement, and he was pleased to play a role in preserving its history.

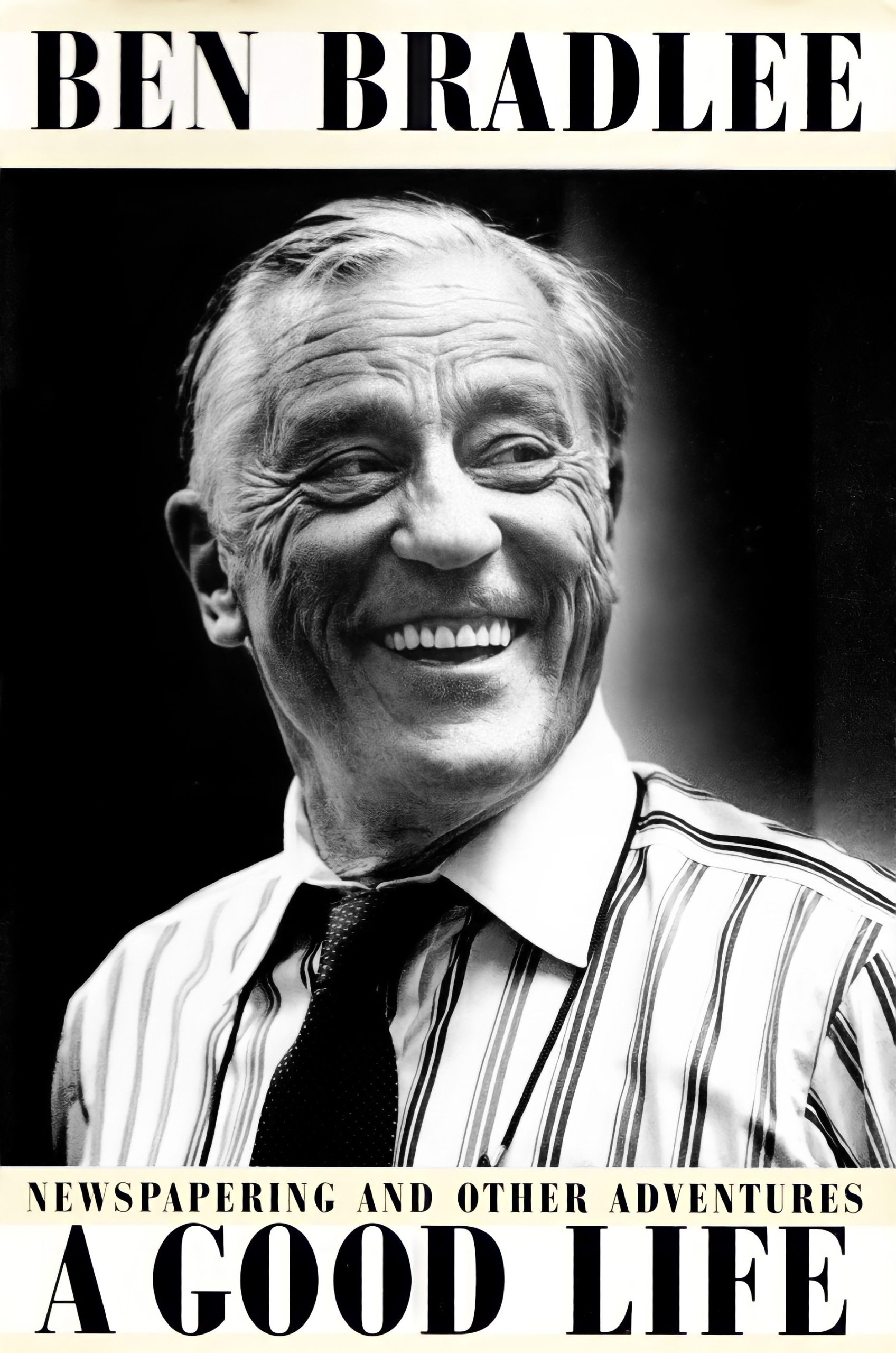

In 1995, Bradlee published a memoir, A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures. By 2007, the French government had forgiven him for his reporting on the war in Algeria, and it gave him its highest decoration, the Legion of Honor. In 2013 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. He died at home the following year at the age of 93. He was survived by four children, ten grandchildren and a great-grandchild. His oldest son, Benjamin Bradlee, Jr., became an author and editor of The Boston Globe, and received the Pulitzer Prize for his paper’s investigation of child abuse in the archdiocese of Boston.

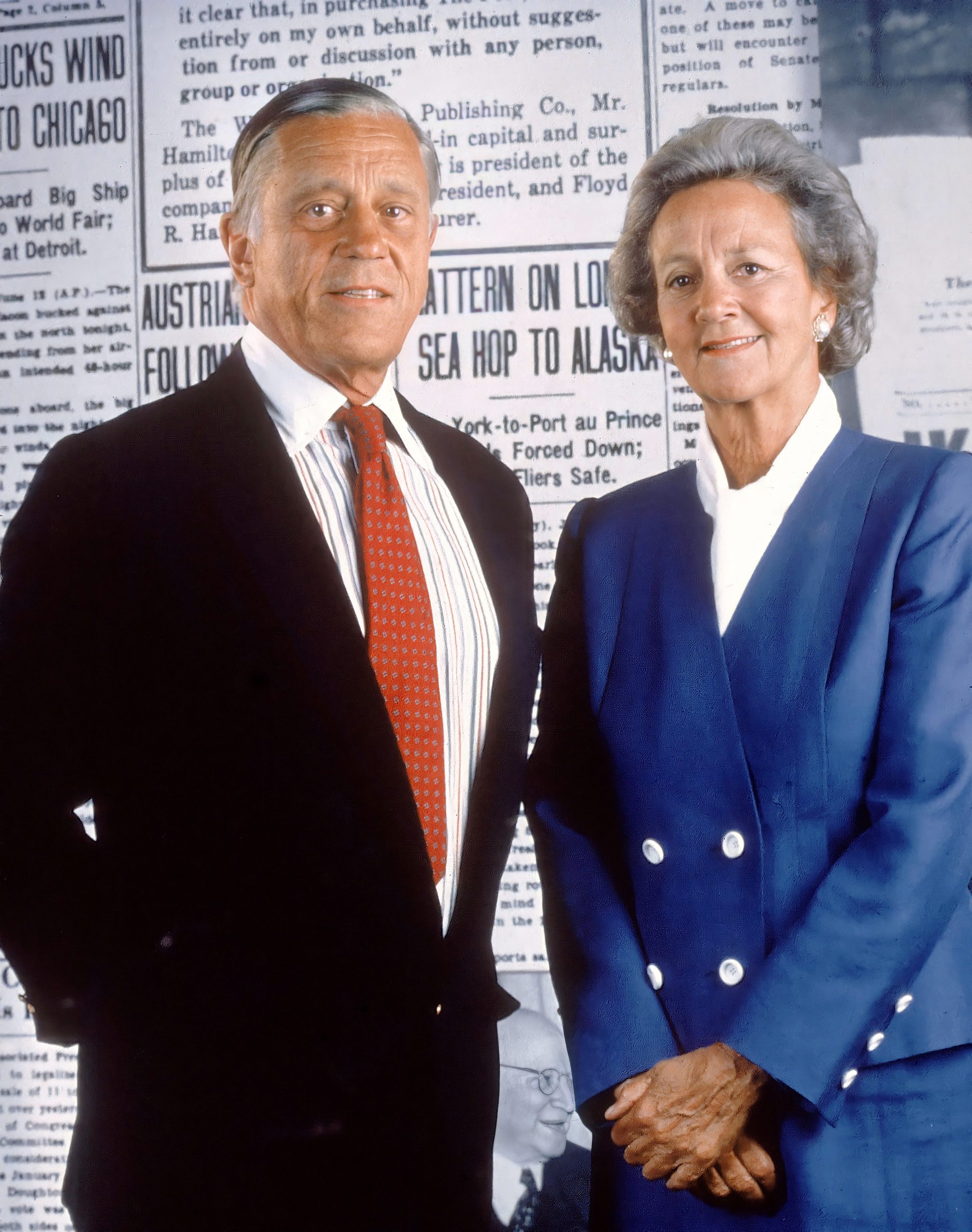

As vice president and executive editor of The Washington Post, Benjamin Bradlee guided the leading newspaper of the nation’s capital for nearly 20 years, through some of the most dramatic episodes in the history of American journalism.

After serving as a communications officer in the Navy during the Second World War, Bradlee founded the New Hampshire Sunday News and served for a time as the press attaché to the American Embassy in Paris. He worked as a European correspondent for Newsweek magazine, covered the presidency of his friend John Kennedy for The Washington Post, and became the Post‘s executive editor in 1968.

At Bradlee’s insistence, the Post risked criminal prosecution by publishing the controversial Pentagon Papers, a devastating exposé of government deception in the Vietnam War. When the trail of the Watergate conspirators turned cold, Bradlee urged his young reporters to continue the investigation. The Post‘s coverage earned the paper one of its numerous Pulitzer Prizes. His autobiography, A Good Life, was published in 1995. Benjamin Bradlee died in 2014 at the age of 93. His remarks on Watergate are interspersed throughout our interview with Bob Woodward.

(The Academy of Achievement interviewed Ben Bradlee and Bob Woodward, the award-winning investigative journalist of The Washington Post, on May 1 during the 2003 International Achievement Summit. Their interviews are combined here.)

Mr. Woodward, can you tell us about the night you first got that phone call about a break-in at the Watergate?

Bob Woodward: June 17, 1972. I had worked for the Post for nine months. They had this — it looked like a local burglary at the Democratic Headquarters, a police story. I covered the night police beat. It was a Saturday morning, I think the summer. Editors looked around and thought, “Who could we call in? Who would be dumb enough to work on this story on a Saturday morning?” And they thought of me immediately. So I went to work with about seven or eight other people, including Carl (Bernstein), and I went to the arraignment of the five burglars, and the judge wanted to know where one of them worked, and he was mumbling. He wouldn’t say. Kind of going, “CIA.” And the judge said, “Where?” And he went, “CIA.” And the judge said, “Speak up. Where do you work? Where did you work?” And he went, “CIA, Central Intelligence Agency.” And I know my reaction was one of “Oh! This is not your average burglary.”

Why did they think of you? You mentioned that you had been at the Post for nine months. How long had you been at the previous paper?

Bob Woodward: One year exactly. So I did not have two years’ experience. I was the lowest-paid reporter at The Washington Post, because they would only give you credit with the Newspaper Guild if you had worked for a daily, and I had worked for a weekly.

What an incredible jump in your fortunes as a journalist, from one year on a little suburban paper to The Washington Post. How did you do that?

Bob Woodward: I was not married at the time and loved being free to do something. I worked quite hard, did a number of stories that the Post and The New York Times picked up. The Post is a very competitive institution, and I think that was the main reason.

How old were you at the time of that break-in?

Bob Woodward: Twenty-nine.

Mr. Bradlee, when did it become clear to you that the Watergate break-in was something more than a simple burglary?

Ben Bradlee: Probably the first or second day, really. It was strange. You had a lot of Cuban or Spanish-speaking guys in masks and rubber gloves, with walkie-talkies, arrested in the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at 2:00 in the morning. What the hell were they in there for? What were they doing?

The follow-up story was based primarily on their arraignment in court, and it was based on information given our police reporter, Al Lewis, by the cops, showing them an address book that one of the burglars had in his pocket, and in the address book was the name “Hunt,” H-u-n-t, and the phone number was the White House phone number, which Al Lewis and every reporter worth his salt knew. And when, the next day, Woodward — this is probably Sunday or maybe Monday, because the burglary was Saturday morning early — called the number and asked to speak to Mr. Hunt, and the operator said, “Well, he’s not here now; he’s over at” such-and-such a place, gave him another number, and Woodward called him up, and Hunt answered the phone, and Woodward said, “We want to know why your name was in the address book of the Watergate burglars.” And there is this long, deathly hush, and Hunt said, “Oh, my God!” and hung up. So you had the White House. You have Hunt saying “Oh, my God!” At a later arraignment, one of the guys whispered to a judge. The judge said, “What do you do?” and Woodward overheard the words “CIA.” So if your interest isn’t whetted by this time, you’re not a journalist.

What a story.

Ben Bradlee: It’s a good story. Not bad, as they say, and what legs! You have kids who weren’t born at that time doing term papers on it at colleges and high schools.

Mr. Woodward, once you heard one of the burglars say he worked for the CIA, where did you take it from there?

Bob Woodward: Is the CIA connected to this? Well, it turns out a lot of CIA people were, and they tried to use the CIA to cover up the FBI investigation, but they never pinned it on the CIA. It was a White House operation. So you would not go from the CIA to the White House instantly, but within several days, through the work of another reporter, we learned there was this cryptic entry in the address books of two of the five burglars that very simply said “H. Hunt – W. House.” So I called the White House and asked for Mr. Hunt, and he came on, and I said, “Why is your name in the address books of these two burglars who were caught in the Democratic Headquarters?” And he screamed out, “Good God!” and hung up the phone. And there was a sort of, as I have said, “I am packing my bags” quality to his voice that didn’t tell you everything you needed to know but certainly got you focused on, you know, this is interesting now. And it turned out he had worked for the CIA for years, had been working in the White House as a consultant to Chuck Colson, who was then Nixon’s hatchet man.

So this was over a period of days, I take it, that it got interesting.

Bob Woodward: Yes, and each week it got more and more interesting. As a colleague of ours at the Post, Bill Greider, wrote the day they disclosed the secret taping system in the White House. I think the lead of his story was, “Will the wonders of Watergate never cease?”

Mr. Bradlee, there is a scene early in the book and the movie, All the President’s Men, in which you criticize Woodward and Bernstein for their approach to a story about E. Howard Hunt, and his interest in Chappaquiddick and Ted Kennedy. What was that about? Hunt had been studying Ted Kennedy and checked books out of the library

Ben Bradlee: A book had been taken out of the library. When we found out who had taken it out, it was Hunt, and everybody said, “What the hell is Hunt doing taking a book on Teddy Kennedy. Why is he interested in that?” But every Republican in the country was interested in Chappaquiddick, and not a few Democrats, so I said, “Find out what the hell he took it out for. Maybe we have a story and maybe we don’t.”

So all the while that this was coming out, you were being very careful that there was enough confirmation of these things?

Ben Bradlee: We were being very careful. As the stakes increased, and as the White House looked more and more threatened, and Nixon himself looked more threatened, and his office became threatened, we just were determined that we weren’t going to make any silly mistake.

Were there any mistakes?

Ben Bradlee: One.

We made one mistake in a story in which we said that — Woodward and Bernstein said — that there was a slush fund of $300,000 set up in the Committee to Re-elect the President, and it was controlled by Haldeman, and that one of the witnesses had testified to that slush fund to the grand jury investigating Watergate. I have forgotten which one it was. But the following morning, Dan Schorr of CBS — we saw on CBS Morning News— shoved a microphone in front of this guy and said, “The Post says you did this. Did you?” and he said, “No.” And the whole town shook, as far as I’m concerned, because that was the first time we had been accused of getting anything wrong. What it turned out was that the question hinged on whether or not he had told that to the grand jury, and since he hadn’t, he was able to say “No.” He wasn’t asked was there a slush fund, which, of course, there was. It turned out that he hadn’t been asked, and that interested us a great deal, because if the prosecution wasn’t asking him those interesting questions, that suggested that there was a reason they weren’t, and the reason might be that they were trying to cover it up. Anyway, it took two days, and we got confirmation that there was, and in fact there was a slush fund of $750,000. So that gave hope to the Republicans, and of course, all of the Republican spokesmen had a field day beating us upside the face over that, but it didn’t last very long. Thank God.

This was a long process.

Ben Bradlee: Four hundred stories about Watergate in The Washington Post. Four hundred in two years and two months.

Mr. Woodward, there were mistakes made during Watergate, you have said in the book. What were some of the mistakes?

Bob Woodward: We accused some people of things they didn’t do that were based on some reports, written reports. We said Haldeman had controlled the secret fund, according to the Grand Jury testimony of the Nixon Committee treasurer, and he had not testified to that. The story was true, but he had never testified to it because they never asked him.

Mr. Bradlee, at what point did you get the inkling that the Oval Office was involved? Do you remember?

Ben Bradlee: Well, right away, with Hunt’s name and the White House telephone number in there.

And Nixon himself?

Ben Bradlee: Nixon himself? I can’t remember, but there were so many. Haldeman? Yes. Ehrlichman? Yes. All of the guys who later went to jail. Mitchell? Yes. It was inconceivable that Nixon wasn’t. But of course, that all became academic when the tapes came out. It came out in the Ervin Committee hearings in the Senate. We were told that before we could write it, but yes, we knew it. It was so important. The whole reputation of the paper was hanging on that by the time. There was an election on in ’72, and most of the rest of the country was saying, “The Post is just playing politics,” and all that stuff.

Mr. Woodward, at what point did you realize that President Nixon was implicated in this?

Bob Woodward: Quite late. We were reporting on the president’s men, and the White House people, the Attorney General, John Mitchell, people in the Nixon campaign, the Committee to Re-Elect the President, and the focus was not Nixon. It was only later, when Dean testified, and the tapes came out, that it was quite clear that not only was Nixon involved, he was in charge of the cover-up.

And that this wasn’t just a cover-up of a burglary. For example, talk about how it affected Muskie.

Bob Woodward: That’s right.

That was the key. The important discovery for Carl and myself was that Watergate wasn’t isolated. There were other burglaries. There was the whole intelligence-gathering apparatus. There were spies in all the Democratic candidates’ campaigns that had been planted and paid by the Nixon campaign. That they would sabotage campaigns. Things that seemed to be simple and innocuous but were quite devastating, false press releases, and accusing people of various activity and so forth, and a kind of sowing the seeds of discord.

There was a letter forged, saying that Muskie had made some disparaging remark about Canadians, and Muskie got very upset. It was never conclusively established that this had been done by the Nixon campaign, but one of the people in the White House acknowledged to one of our reporters that he had written it. Muskie, in the emotion of the campaign, was trying to explain what had gone on. There had been some disparaging remarks made elsewhere about his wife, and he cried, in the snow, in New Hampshire, standing on the back of a flatbed truck, and it’s generally believed that was the end of his candidacy. And of course, Muskie was going to be the strong candidate against Nixon.

It seems to me that to be a topnotch investigative journalist, you have to have a lot of guts in order to question some of these things.

Bob Woodward: No. The guts are supplied by the owners of the newspaper and the editors. They have always backed what I do. I’m out there doing it, and if there’s pressure or debate or controversy, they’re absorbing that pressure. Certainly during Watergate, it didn’t get transmitted to Carl Bernstein or myself through them. They said, “Keep going. Get to the bottom of it.”

Didn’t you have a chat with the Post‘s publisher, Katharine Graham, in the midst of all of this?

Bob Woodward: About six months after Watergate, after Carl and I had written many of — almost all of — our main stories, she called me up for lunch. And she had a style of “I want to know what’s going on. I want to offer some ideas. Kind of parse it out.” But she wasn’t the editor. She was the publisher. She had what I call “Mind on, hands off.” She was intellectually engaged in the news, but her hands were not directing, not saying, “Investigate this, don’t investigate that, give the emphasis here.” That was Bradlee and the editors’ job. But she was quite curious, quite well-informed, plugged in. And she said, “When will we know the full story of Watergate? When will all the truth come out?” Quite optimistically. She posed this, almost suggesting that it was inevitable. And my reaction was, I told her, “Well, Carl and I think that it will never come out, that Nixon and his White House are so good at obscuring things, of sealing off information, preventing disclosure, that we’ll never know.” She looked at me quite stricken and said, “Never? Don’t tell me never.” And I remember thinking and feeling quite motivated that she was saying the standard here is the bar is quite high. “Don’t tell me ‘never.’ Get to the bottom of it.” That your resources, the resources of the newspaper, should be directed at completing this story, getting the full tale, if you would. And it in many ways is, I think, the principle under which she and her son, Don Graham, tried to run The Washington Post. “Don’t tell me ‘never.’ Don’t let things elude us. It’s our job to figure them out.”

Mr. Bradlee, it’s important to remember that Nixon was reelected during this period.

Ben Bradlee: By an overwhelming margin, as we were reminded so often.

But you decided to “back the kids.”

Ben Bradlee: I backed the kids.

That’s a quote from the movie and the book. What made you “back the kids,” Woodward and Bernstein?

Ben Bradlee: Because the kids were right. They were not hard to support, these young reporters, because they were right. Every time the White House denied something, the evidence became clear that it was the White House that was lying. First, the spokesmen at the White House, Ziegler and some of those guys, and next the Attorney General, and Chuck Colson, all of those people, the White House aides, were lying. Robert Dole, and Dole’s successor as the chairman of the Republican Party, George Bush the first. These guys lied because they didn’t know the truth, and they couldn’t believe that they were being lied to.

Nixon didn’t last too long in that second term. Where were you when he resigned, and what were your feelings?

Ben Bradlee: I was at The Washington Post, and I couldn’t believe it. I mean, I believed it, because it was — I knew it was coming. I really — we knew it, we knew it, we knew it, but we couldn’t — we were being told by the people who were telling us that if we publish it, he’ll change his mind and won’t resign! So we started phrasing it “close to resignation,” and “debating resignation,” and then, finally, we learned that — I think he was going to do it at nine o’clock at night, or eight o’clock at night. He resigned. Well, I was down there. Where the hell? I mean, I lived in that place for those periods. And we were so scared that we were going to — by this time, we knew that the front page was going to be a historical document. It was going to be reproduced in the history books, and we wanted to be sure that we got it right, and be sure that some — there wasn’t a typo. In those days, you worried terribly about typos. We wanted to be sure that it wasn’t sabotaged in some way by, you know, printers slipping in the “F” word or something like that that was going to screw it up. And we had to be sure the headline was right. We had to be sure. Just — it was terribly, critically important that we do it right and that we not brag, not seem to be bragging, and that we didn’t allow any television in there for days.

I was worried about the Post‘s image of all of this, and that there would be a segment of society who said, you know, “They were out to get him, those bastards, and they got him.” And it was going to be — we were just very careful. We had such good sources. One of the sources I can now reveal — I mean, I have talked about — was Senator Goldwater, who was a great friend of my wife’s family, and I used to talk to him all the time. I’d have drinks with him early — all of late July and early August. And he would be going over to the White House to give Nixon the news that he didn’t have any — his support in the Senate was eroding. And he was the one who said that. He told me first that he was going to resign, wasn’t sure when, and for God’s sake don’t write it as hard, because he won’t. So we were terribly worried, and we didn’t — it’s a big newspaper and a lot of people in it, and you can’t control all of them even if you wanted to. So we tried to just keep people out of the building. We didn’t allow any television people in. We didn’t allow television in for six months, I don’t think. And when Redford wanted to film the movie in the Post, we told him he couldn’t. He wanted to film it from 3:00 in the morning until 8:00 in the morning, and we just told him it was not possible.

Mr. Bradlee, what were your emotions when Nixon resigned?

Ben Bradlee: That we had really done a really good job. That the difficulties they put up to prevent the truth from coming out had been overcome. That really is what we’re all about. Let’s be sure for the record to say that it wasn’t just the Post. The Post played a critical role in the beginning, and Woodward and Bernstein came in at critical moments. They were the first to reveal the tapes, and they were always ahead of the curve, but there was a lot of great reporting done by other people, Sy Hersh, the Los Angeles Times, they all did really good work.

Mr. Woodward, tell us what it felt like to you personally when Nixon stepped down.

Bob Woodward: We had done some of the early stories, that it led to the Senate Watergate Committee, led to the House Judiciary Committee and impeachment investigation. Special Prosecutor Cox and Jaworski investigated this, put lots of people in jail. The Supreme Court ordered the president to turn over his tapes, which really sunk him — the “smoking gun” tapes — at the end. So I had just a sense that — we had done some of the first work on this — that any suggestion that we had caused it, or brought down a president, was a stretch, to say the least, and not factual. That we had done stories, but it is a process of the judiciary, the Congress, the Supreme Court, that led to Nixon’s demise. But then, of course, if you think about it, Nixon is the one who did himself in. The piston driving the Nixon administration was hate. Nixon was a full-blown hater, and if you listen to the tapes, it’s chilling and frightening.

Paranoid too. Right?

Bob Woodward: Well, paranoid, and…

He wanted to use the presidency as an instrument of personal revenge, to settle scores, too often, and that’s not what the presidency is about. And what’s sad about the Nixon presidency is not just the criminality and abuse of power, but the simple truth, to the best of my knowledge at this point, on those tapes no one ever says what would be good, what would be right for the country, what would be best for the country, which of course is what a president is supposed to do. It seemed to always be about Nixon. “How does this affect me, Nixon, the president? How do I pay someone back, either good or bad, for what they have done to me?”