You’ve certainly addressed this question in your first book, but to begin with, what was your childhood like?

Frank McCourt: It was rich in the sense that, even though we were poor, at the lowest level, even below the lowest economic level, we were always excited. It was rich in the sense that we had a lot to look up to, to look forward to, a lot to aspire to, a lot to dream about. But in economic circumstances it was desperate. It was Calcutta with rain. At least they’re warm in Calcutta. But it was desperate because of certain things, ingredients like my father being an alcoholic, my mother having too many babies in too short a time, no work available in Ireland, and even when my father did get a job he drank the wages. Then there was the harsh kind of schooling we had with school masters who ruled with a stick and then because of the overwhelming presence of the church, which imbued us with fear all the time. So it was fear, dampness, poverty, alcoholism, fear of the church, fear of the school masters, fear in general.

But at the same time when we got out of school, when we were away from the church, when we were out of the house, we were on the streets and we were always excited. And when you have nothing little things become very precious, like books. There was an occasional book that came into our house and we just devoured it. In that sense it was very rich.

Were there specific books that were important to you as a young person? Books that inspired you or influenced you in some way?

Frank McCourt: I think the first book that I ever read was Tom Brown’s School Days, which my mother bought for me at Woolworth’s in Limerick for sixpence. One of those pulp—cheap pulp books. And I treasured that. And then occasionally other books came into our area but we couldn’t just go out and buy books and there was not a library for children. There was a Carnegie library for adults. But we didn’t have books. So when Huckleberry Finn came in I — I wanted to be Tom Sawyer. I wanted to go down to the river Shannon and stand at the banks of the river, and did, and dreamed it might be the Mississippi, and I’d get a raft and off I’d go 60 miles out to sea. And I wanted to be free like Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn.

But these were the books that made a big impression on me. The main literature in our lives was the literature of the church: the Sunday missal and the lives of the saints. Since books were so scarce I can remember all of them, even the look of them and the smell of them.

Did that make them all the more precious?

Frank McCourt: Oh yeah, everything was precious. I remember a loaf of bread that was precious because it was so little. My mother would bring home what they called a Vienna loaf. I remember one particular loaf of bread when we were so hungry. I can still taste it. So poverty does make things precious. It turns everything into jewelry.

What about teachers? In the midst of that harsh schooling are there teachers who influenced you or opened up possibilities for you?

Frank McCourt: They didn’t have the human touch that American teachers have, I think, but they did other things and they ruled in a way. They had style. When I get together with my people my own age and talk about Leamy’s National School, we can still talk about all the teachers, how distinctive they were, from the first teacher, Tom Scallon, who taught the first grade. At the end of every day Tom Scallon became the music teacher. He’d stand us up and we’d sing in Irish and English and Latin. He had a way of teaching that was fairly brutal but still very musical, and he taught us all the Irish ballads, and some American stuff, and Gregorian or plain chant.

The last teacher I had was a man named O’Halloran. But he was the only one who offered words of encouragement, who told us we were distinct, unique individuals with a right to think for ourselves. And that was just before we left Leamy’s National School. And he told me, “My boy, you are a literary genius.” And you can imagine what I had to put up with at the schoolyard with all the others. “Hey, McCourt, you’re a literary genius. Look at him. Look at the literary genius.” But it wasn’t negative. It was just teasing. But they respected him and they respected me for being picked out by Mr. O’Halloran.

Were you a good student?

Frank McCourt: I was, I suppose, because there was no choice. They’d beat the hell out of you if you didn’t do your work. Some of us were quicker than others. Some kids were very slow and they suffered from it because the masters would get irritable. They wanted you to know, and if you didn’t know, if you didn’t comprehend, they would haul you out of your seat and knock you around the room, which is not advanced pedagogy.

What did you do to earn this label of literary genius at such a young age?

Frank McCourt: I think I was always attracted to writing. I always wanted to write because for me it was magic to get a piece of paper and put words on it. As I’m always saying, to put together words that were never before put together by anybody. To take two words that were never joined together like a “scintillating turnip.” I would put words together like that just to keep the language fresh. When I was nine or ten I was trying to write a detective novel, an English detective novel, set in London, which I had never seen. All I knew about London was what I read in English detective novels. So I was always up to something like that, and writing little playlets that I’d make my brothers act in.

I wrote one play about how my youngest brother, Alfie was lost. He was only one, and there was a nail on the wall, and we hung him on that nail by the back of his shirt, and then we forgot about him. My mother came home and she says, “Where’s the child?” And we couldn’t remember. -“Where did you put him?” We couldn’t remember and we found him hanging on the wall. I think he’s been damaged by that ever since. But I would go on writing stuff like this.

In school if they told me write an essay of 150 words I’d write 500 words, so the masters said, “Stop, McCourt. Stop. That’s enough. Stop.” And then they might read it to the class and then, of course, I’d be teased again in the schoolyard. “For Jesus sake, McCourt, will you stop writing? We have to listen to it.”

Mr. O’Halloran used to take my compositions home and read them to his kids who went to private school. I was always scribbling.

So despite the poverty, despite the hardships, education was an important part of your life.

Frank McCourt: Oh, yeah. That was the elementary school, primary school. They made it important. But at the same time we knew — being in the school we were in, Leamy’s National School — that after the eighth grade we were finished. School was mandatory until you were 14. We were not going to high school, secondary school. We would become messenger boys or unemployed, or roam the streets, or somehow get to England.

Why?

Frank McCourt: We were considered the hewers of wood and the haulers of water. Our schooling ended at 14. We came out of the slums. People who came out of the slums were not expected to go to secondary school because I went to what they called a national school, which is a government school. And there was no expectation. We couldn’t afford to go on to secondary school anyway. I couldn’t have afforded the books or the clothes. We didn’t have the clothes. A lot of the kids were barefoot and we all — you know, I wore the shirt I went to bed in, the shirt that I wore all day, and wore it the next day until it fell off my back. So when you went to secondary school you were expected to come mainly from the middle class or the upper working class. We belonged to none of those classes.

So you left school when you were 14?

Frank McCourt: Yeah, I was actually 13 when I was finished.

What did a 13-year-old do?

Frank McCourt: A 13-year-old waited until he was 14 and then I got a job at the post office delivering telegrams. You had to take kind of a test to get into the post office for what they call a temporary telegram boy and then you could later go to school and get the permanent telegram boy job. And if you got that, then later on you could become a postman and maybe a clerk in the post office selling stamps and maybe rise in the ranks and become an inspector. Well I went in at 14 and I delivered telegrams for two years. I knocked on every door in Limerick. The population of Limerick at that time was about 55,000. So I think I knocked on every door in Limerick, threw telegrams in the window, under the door, everything, was attacked by dogs and irate people who didn’t get the telegram they wanted. They’d attack you literally.

A lot of the women in Limerick were widows from the British Army. They used to get pension payments and if you brought a telegram from somebody else wishing them “Merry Christmas” or something like that, and it wasn’t a telegram from the British Army, they’d attack you because they were so frustrated waiting for the money. They’d take one look at it and then look at you and then you knew the attack was coming. So you’d run down the path and hop on the bike. So I became a psychologist; I could see anger coming.

I did that for two years, and then I was encouraged to take the exam for permanent telegram boy and the morning came and my mother wanted me to do it so that I would have a bigger income and security and the pension, and I’d get a uniform. As a temporary you didn’t get any uniforms and we were out in all kinds of weather just with a jacket on or a sweater. Pouring rain, we were always wet. I don’t know why I didn’t die of TB.

The morning of the exam I went down to the building. The headquarters was in something called the LPYMA, Limerick Protestant Young Men’s Association. I went as far as the steps to go in. I was handing the man my form, and I drew back. He said, “Are you coming in or what?” And I said, “No. No.” And I went home.

I hung around for a while before I went home. I wanted my mother to think I took the exam, but she found out that I hadn’t taken it and she was furious. But it was the right decision, because three years I went to America.

What influence did your parents have on you?

Frank McCourt: My father was an alcoholic. By day, when he wasn’t drinking, he was the perfect father. When he’d get money then he was a maniac. He was two different men. I know this is a racial generalization but it was typical.

The country was so inhibited emotionally, I think, because of the church and because of the traumas that arose out of history, like the potato famine. The people had gone into themselves and it wasn’t like that in the old days, way back in Medieval Ireland when they sang and danced in a wild orgiastic way. In my generation and the generations before me, the people had gone inward.

So my father would sit by the fire and read the paper. He was very laconic but at the same time he would tell us stories and teach us songs. My mother was depressed because she had lost three children, but we learned song from them and we learned storytelling.

My mother was always amused by my father. He had a laconic sense of humor, and she was a good storyteller too, because she’d go to the movies and we couldn’t go. We didn’t have the money. She’d come home and tell us the whole movie frame by frame. She went to see a movie once called Reap the Wild Wind with Paulette Goddard and John Wayne who was a bad guy in there, and Ray Milland, and she told us every line of that and we sat around the fire. I remember that fire, looking into the flames darting and leaping, and she’s telling the story and we’re having tea. So this is what we got from them. No television. There was no television. No. We had none of that. We had no electricity so we couldn’t have anything. But there was always this stuff going on between us at home and in the streets and with the neighbors. That was rich.

But then my father would ruin the whole thing with his drinking. He really drove my mother to the wall. He drove her into a nearly fatal depression with the drinking. If he got a job and he was paid on Friday night, there was kind of a dramatic element to this.

The men got out of work, out of the factories and the timber yards and the cement factories at 5:30. They would come home on Friday night, most of them, wash themselves to here, from here to here, never below. No, people didn’t touch themselves with water from one end of the year to the other. They’d come home, wash their hands, throw water on their faces, have their Friday night tea, which was an egg because it was Friday, and then the women would give the price of a few pints and they’d go out and they’d have a few pints, talk, sing a few songs, come home, have tea, go to bed, and go to work the next morning. Five thirty, they were out. By six o’clock most of them were home for that wash and their tea. The Angelus would ring all over Limerick in all the churches and the women would wait, but my mother would wait on tenterhooks. If he wasn’t home by 6:00 o’clock, boom, boom, bong, bong all around the city. If he wasn’t home by the time the Angelus rang, he wasn’t coming home and then she’d sink deeper and deeper into the chair by the fire, because we knew then the wages were gone and he’d arrive home after the pubs were closed, roaring and singing down the lane, “Roddy McCorley Goes to Die,” and all the patriotic songs. He grieved over Ireland and didn’t care if we starved to death that night and the next day. So that was the atmosphere I grew up in.

As a child you almost died of typhoid.

Frank McCourt: I had typhoid. Yeah, because there was a lavatory that we all shared in this lane. All the families came and emptied their buckets. They used the bucket in the house, in the bedroom, for everything, and then emptied it into this lavatory. And it would overflow and there was waste, dirt, pee, piss, excrement everywhere. Flies, rats, everything coming to — were attracted to this lavatory. And our door would be open and our door was catty corner with the door of this lavatory. We could hear them coming. We’d say, “Oh, God, shut the door. Shut the door. Bonnie Sexton is coming with her bucket.” And she had the worst bucket in the lane. We became connoisseurs of the stink. So the flies would go in there, and they’d come in and they’d settle on the sugar bowl that we had. When we had jam, they’d be lapping at the jam, and I got typhoid fever out of it. And in those days they didn’t have the medicines, or if they had them they weren’t available to the likes of me. So I spent three-and-a-half months in the hospital in the summer, which nearly killed me.

If you’re going to get sick, when you’re a kid, you want to be sick during the school year. I was very bitter to have to spend the summer in the hospital: June, July, August, September and into the middle of October.

Did it ever occur to you that this was the makings of some epic tale?

Frank McCourt: Oh, no. Far from it. We were all ashamed of this. You didn’t go out into the world announcing that you came from some slum. You don’t find kids from the ghettos and the slums bragging about what they came from.

I remember reading James Baldwin talking about his mother fighting the cockroaches, trying to keep the kitchen clean, trying to keep things growing up in Harlem, and I said, “That’s it. This man understands,” because you read so little about poverty in American literature or any other literature. There was Dickens, I know, but Dickens — I became suspicious of him because he had all those happy endings. I wish Oliver Twist had died of TB, or David Copperfield. That used to piss me off when they’re all — they all found out they were related to somebody in the Royal Family or some damn thing. So when I came across Baldwin and George Orwell’s book Down and Out in Paris and London and another one called The Road to Wigan Pier, they had — he knew. He knew the details, the stink of poverty.

So when I was growing up I wasn’t particularly proud of it. None of us were when we finally left. Even around Limerick, if we wandered out of our lane, we went into other areas, more prosperous areas of Limerick,

We didn’t want to look like we came from the lane, but you could spot us a mile away. The urchins from the lanes. We had that look. You see kids roaming the big cities, in New York, in America, the inner cities as they say. You see bands of kids and you know. You know where they came from. You can spot them. They’re roaming around. And you look at some of them, they don’t want to be there, they want to be someplace else. They want to be a part of what they’re walking through, the fine streets and the broad avenues. And that’s the way I felt. I didn’t want to be detected as a slum kid, but there was no choice. We had no clothes. We didn’t have clothes. So when I came to New York I tried to pass myself off as middle class. I even tried to affect an American accent. It didn’t work. I tried some days. Even nowadays my wife falls on the floor laughing at my attempt at an American accent. So we all wanted to sound like James Cagney.

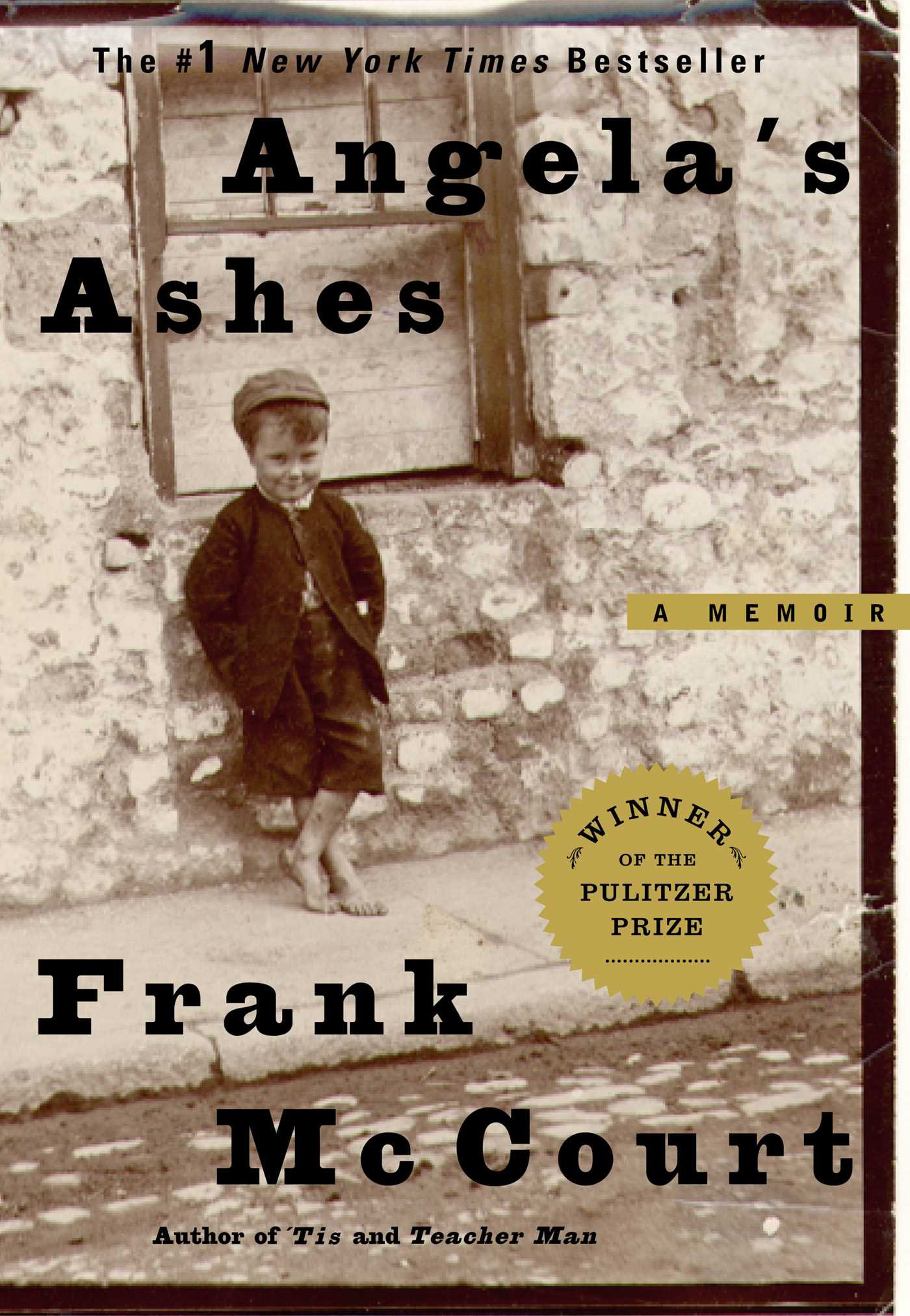

But we didn’t want to tell anybody what we came from because we were ashamed of it. And concurrent with shame is anger. When we joked around about this in New York, my brothers and I, my mother would say, “Will you stop talking about that? That’s the past.” Eventually we got over the shame and we started talking about it. It took me a long time and then I started writing about it in my notebooks and that led to Angela’s Ashes a long time later on.

In this story of triumph over poverty and hardship, there is still humor and compassion. What is the importance of humor and compassion in your story?

Frank McCourt: I think if you talk to anybody who has come out of adverse circumstances they’ll tell you that humor keeps you going. That’s the way it was in the lanes and the slums of Limerick. As poor as people were, they sang, they told their stories, and they laughed. They laughed over the neighbors. Limerick, Ireland, has been called an open air lunatic asylum. People wander the streets of Limerick who are, you know, a bit daft. In America they’d be locked up in a minute.

And then we would imitate the teachers. We would go home from mass on Sundays, and if there was a particularly powerful sermon by a Redemptorist preacher, you’d always find me up on a chair giving a sermon and my mother would say, “Would you get down, you old eedjit!” But sometimes she would sit there looking and laughing.

We’d come home from school imitating the school masters. We’d imitate policemen, bureaucrats giving out the welfare down at the dispensary. We imitated and made fun of everybody and even ourselves. We’d tease each other. I remember laughing in a way in Ireland that I’ve never laughed since.

We’d go up the road, we urchins, and swim in the Shannon. We’d tell each other stories or carry on and literally fall on the ground laughing. There was this excitement and the sense of joy in life, with our low expectations. We were satisfied with a slice of bread and jam. That’s it. We didn’t know it, but humor was one of the things that was keeping us going.

I’ve heard that even in the concentration camps they would put on little playlets in these huts, mimicking the guards and so on. If you don’t have it, if you don’t have that particular chemical, you’re dead.

After coming to America, you served in the U.S. Army and went to college on the GI Bill. You went into teaching. Was that your plan?

Frank McCourt: Yeah, I went into teaching. My dream existence would have been to have a loft or a small place in the Village, and to write there, and to hook up with a ballerina. I wanted to live with a ballerina because I imagined all kinds of wild physical things. We’d have this loft, and she’d go off with Balanchine every day and do her steps and she’d come back in the evening and we’d have wine. Wine, cheese and an apple, and fine bread, and then we’d just go at it on the floor of the studio, and she’d do fantastic things with her legs.

That didn’t happen.

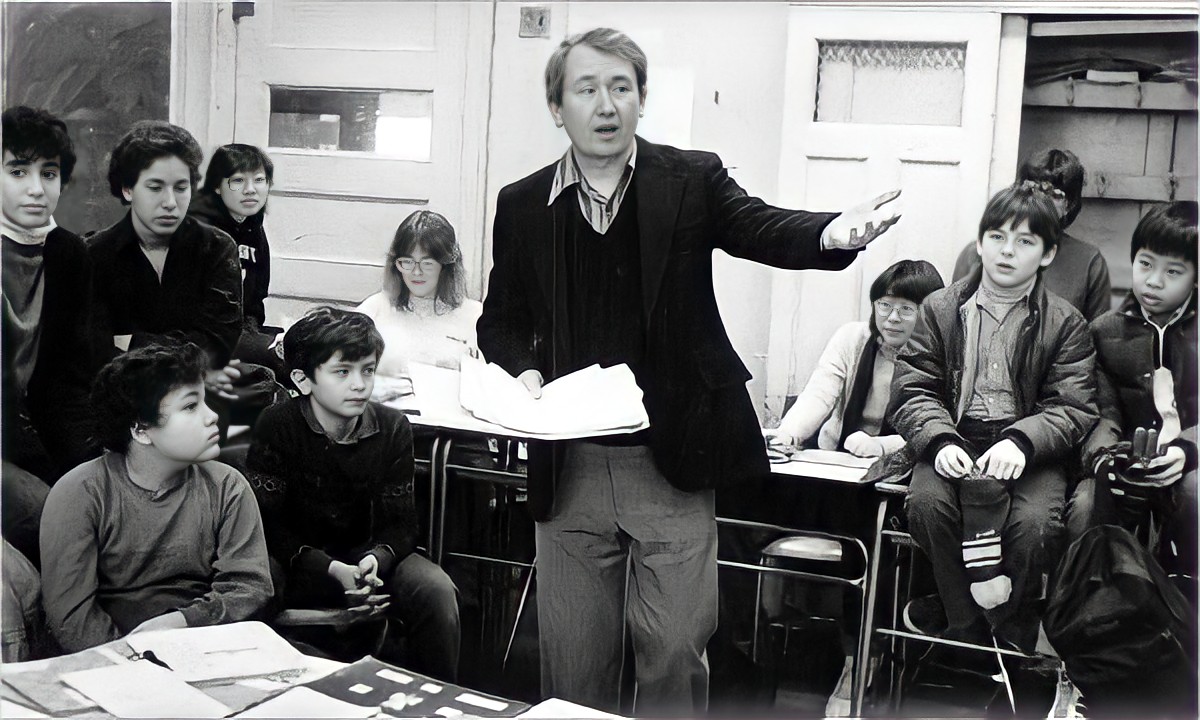

Frank McCourt: That didn’t happen. I became a teacher, in a very rough school. There was no lolling about the floor. It was getting up in the morning at 6:30 to take the ferry to Staten Island to McKee Vocational High School, and to go into a class — five classes of tough kids who were not a bit interested in what I had to say, so I had to hook them, and I was thrown into this. As I told you before, I had no high school education myself. I had never been in a high school so I had to — I was — nobody told me what to do. They just threw me into the classroom and here I was in front of these American teenagers who were a species from another world from me.

What did you learn from that experience?

Frank McCourt: I learned to drop the mask. I went into the classroom as — my only models were Irish school masters and I thought I’d go in there and I’d roar at the kids in McKee Vocational High School the way the masters roared at us. It didn’t work. “Yo, Teach, why you talking like that?” And they were talking to me. I’m the school master, “Yo, Teach,” and I had to stop this. I had to find some other way of dealing with the kids, of running the classes, and I found eventually the only way to deal with them was to be honest, to just try to get to them. I didn’t know how. I found it very difficult to even deal with people on a one to one basis because we put up so many defenses when we were kids. And we were so angry all the time that even in the one-to-one situation in New York, if somebody disagreed with me, it got my Irish up so to speak, and I’d get angry. I couldn’t realize that this is a person who just wanted to discuss something. I thought they were opposing me and that would lead to fisticuffs. “Would you like to step outside?” So it took me a long, long time to get over that. And it was only through the teaching I learned to put this anger aside and not to take it personally when the kids would erupt. You know, when you have 150 or 170 high school kids every day there will be eruptions, and they get angry and they direct it at the teacher, but it’s not at the teacher. It’s something they brought from home. You know, you can get all psychological about this, but I learned not to take it personally. I learned not to be quite impassive over it, but to understand what was happening in the classroom. That was the beginning of my education.

You learned from these kids?

Frank McCourt: All the years that I was teaching I was learning. That was the main thing in my life, I think. I became a human being in front of those classes, because I wasn’t. I was kind of a stick of dynamite when I came to New York, and when I started all this teaching. But over the years — in McKee, the years at Seward Park High School down in the lower east side of Manhattan, then especially the 18 years at Stuyvesant High School — that was my university, and boy, I’m a late bloomer. It took me a long time to come to grips with myself, never mind the kids, but I learned from that.

I think, in many ways they were more mature than I was, these American teenagers, because when I was 19 my mental age was about 11. That’s what I brought with me from Ireland, the baggage, and the fear, and the anger.

What were you hoping to accomplish as a teacher?

Frank McCourt: I didn’t know in the beginning what I wanted to accomplish. I had to work things out for myself because nobody was telling me. I wasn’t particularly intellectual, I think I moved a lot by instinct, and then a hint at intellect came along after it. I worked out this equation: What am I doing in the classroom? And I wanted to move the kids from what I call “From F to F: from Fear to Freedom.” And I would explain most of us are fearful of something or other. So if I accomplished anything in the class, it was to help the kids to think for themselves, because we had never been encouraged to think for ourselves. We were told we were worthless. The only thing for us to do was behave ourselves, observe the edicts or the pronouncements of the Catholic Church so we could go up to heaven. But eventually I knew the kids lived in a state of fear. Over what? You know, being teenagers, worried about their looks, worried about their popularity with the opposite sex, worried about their future, and I wanted to try to help them think for yourself.

That was a dangerous thing to do, especially at Stuyvesant High School because parents had already imposed their expectations on the kids. “I want you to go to MIT. I want you to go to Harvard.” A lot of kids didn’t want to do that.

I had one kid who wanted to be a classical guitarist. His father said, “Not on my nickel. You’re going to Boston University and you’re going to be an accountant.” And he came to me and he said, “What do I do?” I said, “Who’s paying for the college?” “He is.” “All right. You could tell your father take a running jump and go off and take your chances at the world.” And his father said, “You could be a guitarist on the side. Do it on the weekends, but you’re not going to study music on my nickel.” So he went to Boston and became an accountant. That’s the fear.

I realized the impulse of the parents, how they want their kids to be secure and everything. I realized that, and I realized the romantic dreams of the kids, which were not romantic, they were real dreams, because I had them myself. How do you steer a middle course between the parents and the kids? You have to be careful that you don’t turn kids against parents or parents against kids. So I had to organize this and try all the time to present both sides of the story. That was my main learning experience, and that’s why I don’t take any extreme.

I used to think I was a Democrat, now I’m more independent. I don’t have the energy for one “ism,” to be on one side or the other. If I’m crossing the street, it’s easier for me to look both ways, because if you look just one way you’re liable to get killed. So I go my own way as far as religion is concerned, or politics or anything else. It’s the predictability of a Democratic position or a Republican position that bores the hell out of me. I learned all this because of my particular predicament as a teacher, finding the middle way and having compassion for both sides.

When you started teaching in New York, did you think this was going to be your life, your career?

Frank McCourt: No, I didn’t. Especially in the beginning at McKee Vocational, a technical high school where they nearly killed me. Before that I had worked in warehouses, I had worked on the docks, I had done all kinds of physical work, but I was never so exhausted as I was after a day at McKee High School. I used to go home and throw myself on the floor without benefit of pillow and lie there for two hours to physically and emotionally recover, and I dreaded going in the next day. But something happened.

One morning I was taking the train from Brooklyn into Manhattan, where I got the ferry to go out to Staten Island, and I was getting off the train at Whitehall Street, stepping off the train and on to the platform, and this thought came into my head, “You could decide today to be happy. You could just make a decision, instead of going in fear and trembling into the classroom.” Now it’s easy to say that, and it doesn’t always work, but I realized that I was resisting some kind of gloom, gravity, that most of us, most of the time, we look on the dark side, I think, but you have to work at lifting yourself up but I tried it that day. It was the beginning of that kind of practice.

Then I realized, “If you don’t enjoy yourself in the classroom, get out.” It would have been easier to do what my three brothers did, go into the bar business. Go up there and meet glamorous men and beautiful women on the East Side and stay out all night drinking and have brunch with some long-legged creature from Boston. No. I thought of that but then I thought of the kids in the classroom, and there was something more appealing about that. And besides I wanted to get through. I wanted to get through to them and I wanted things to click, and sometimes in the — there’s something that happens in a classroom that I know actors experience and artists, in general. There’s some time when you make a breakthrough, and some light goes on. One day in McKee I made a breakthrough of some kind, and for me there was kind of a white blazing light in the room and I went, “Jesus, this is absolutely orgasmic in an intellectual and emotional sense.”

We were dealing with a poem and it was called—the poem was called “My Papa’s Waltz.” You’re always telling the kids, “Look for the deeper meaning,” and then there would be a test. But I said to the kids, “Let’s get inside the poem. What’s going on in here?” And there was an explosion for me at that moment because we were doing it together. I wasn’t a teacher anymore, as in “I know everything and you’re just out there. I tell you what you need to know.” Instead I said, “You tell me what’s happening. Tell me what’s going on in here.” That was a turning point that colored my whole teaching career.

So at some point it became more than a job?

Frank McCourt: It had to be more than a job, because as Dylan Thomas said, “A job is death without dignity.” And I didn’t want that kind of life. I had to go into the classroom and enjoy myself. And I’d say to the kids every September, “By the end of this term there’s one person in this class who will have learned something, and that will be me.” And I have to enjoy myself. I told them, “I have to enjoy myself here. I have to do it. You’ll be graduating and I’ll still be here and I’m not going to wither on the vine. I’m not going to be old Mr. Chips. I’m going to swing.”

You taught for 27 years. Your first book wasn’t published until you were in your mid-60s. How hard was it to get your voice heard, to be published?

Frank McCourt: I had no problem. When I was writing the first 150 pages I didn’t know what I was going to do with it but I had to write it anyway. I had to get it out of my system. Then I met a friend at a lunch, Mary Breasted, who used to be a reporter for the New York Times, and she’s a novelist. She asked me what I was writing and I told her I was writing this memoir. She said, “Let me see it.” I said, “No, no, no. You wouldn’t — it’s too — it’s just misery.” She demanded it and she liked it, and she showed it to her agent, Molly Friedrich.

She said to Molly, “You have to read this.” Molly said, “What is it about?” “Miserable childhood in Ireland.” “No, no, no, we have enough of that.” “Read it,” says Mary. Molly read it. Then Molly called Nan Graham at Scribner. “What is it about?” “A miserable childhood.” “No, no, no.” “Read it,” says Molly. So Nan read it. And then the next thing, they bought it. There were only 150 pages. That was in July 1995.

Nan said to me, “When will it be finished?” And I said “November 30th.” And she said, “November 30th, why?” I said, “It’s Jonathan Swift’s birthday.” This was a bit arrogant of me: from July to November I was going to write another 250 pages or so! But I did. I finished it by November 30th and I wrote the last word, which is “Tic.”

My wife Ellen was at work. I said, “I’d like you to come home directly. I want you to be here when I write the last word.” So she came in. We sat down at the coffee table. I wrote the last word and we broke open a bottle of champagne. She was there to see the last word.

The next day I took copies to my agent, Molly, and my editor, Nan. And I had promised myself if I ever delivered a book like that I’d go to the nearest Irish pub and have two pints of Guinness. When I went to Molly’s office, she had champagne so we had champagne. When I went to Nan’s office, she had champagne so I had champagne. Then I went to the Fiddler’s Green on 46th Street, I think, and had two pints of Guinness. When I got home I could hardly find the lock for the key.

In your wildest dreams could you have imagined what happened next?

Frank McCourt: No. It is beyond the capacity of any screenwriter or novelist to imagine what has happened to me in my 60s. So I’m the beacon of hope for the whole Social Security set.

I used to go to a bar called the Lion’s Head down in Greenwich Village and people like Pete Hamill and Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin would come in there. They were publishing books and writing newspaper columns and I was only a teacher.

There was a hall — there were framed book jackets of all the people in there who had written, and the place was swarming with writers. And I had one dream: to have my book jacket framed on that wall. And then the Lion’s Head is closed now. It closed in October of ’96. A couple of months before that. A month before that maybe. Mike Riordan, the owner, he called me and he said, “Come down for a drink.” I said, “Mike, I’m—” “Come down for a drink,” he said. So I went down and I sat at — it’s in the afternoon. He said, “What will you have? Is there anything you’d like?” I said, “What’s — why did I suddenly become this — ” I thought they were generous. “Anything you like.” I said, “Well, I’ll have a Bushmill’s, a Black Bushmill’s.” So I had one and he said, “Cheers.” Then he said, “Turn around.” And I turned around and there was my framed book jacket. That was it. That was — for me, that was the Nobel Prize. To be on the wall of the Lion’s Head just before it closed.

As soon as I do anything, the publication or the pub closes down. If I send a short story to a magazine, they publish it and then they go out of business. But not in this case, not in the case of Angela’s Ashes.

What do you know now about achievement now that you didn’t know when you were younger?

Frank McCourt: My dream has been fulfilled: to have come to this country, to have taught. The day I retired from teaching, again, was one of the most satisfying days of my life and it was sad, but when I — the day I retired, I went home and I was by myself and I was having a glass of wine. I was thinking about the lunch the teachers gave me that day. The retirement lunch. And I was able to look back on that life, that 30 years in the classroom, and say — I was able to congratulate myself. I’m glad I did that. That was good. I felt useful, that I don’t think I would have felt if I had gone into business or something like that. So that was — that was that deep satisfaction that I had, that I had followed some kind of a daily — what would you call it? — discipline. And I was dealing with kids, and I hope that I had been of some use, of some help. You never know. But they’ve told me. I meet the kids, former students, and they tell me that I was of help. So that and publishing the book. What more can a man ask for?

Is that what the American Dream means to you?

Frank McCourt: This is it. For me it’s beyond the American Dream. I think if there’s another place that’s even better than America, maybe heaven or something, I’ve gone beyond it.

So that I could be in a state of paralysis — ecstatic paralysis. But now I know that I have to write another book. Now I know I’m not finished with the schools, that I’m not finished with kids, that I’m not finished with teachers. That goes on and that’s — if I have any mission left, it’s going around talking about the kids and teachers and schools in general.

If you had to, could you say what it took to transcend your circumstances? To get from where you were to where you are today?

Frank McCourt: First of all, I had to overcome the anger, because the anger was paralyzing. I think a lot of the kids knew that. They helped dissipate the anger. They gave me a break. I was kind of an exotic with this accent, from Ireland. Once I dropped the mask, then they were cooperative and I stopped being a phony. That helped me transcend the anger, and the shame and everything else so that I became a teacher in the classroom instead of somebody preaching at the kids. That was the transcendent experience, so that I was able to find myself.

In that sense I was very lucky. You know how, in the corporate world, everybody is putting on an act all the time? If I had gone into anything else, I would have been dead in five years. I would have had ulcers. I would have been out the window. But I was with kids, and they demand honesty. They know when you’re telling them lies and you can’t sustain the lie with them, or the hypocrisy. The teacher was shaped by the kids. Maybe I taught them something in return, but they shaped me.

Is there anything you haven’t had a chance to say that you think kids ought to hear?

Frank McCourt: Everybody says follow your dream, or Joseph Campbell would say, “Follow your bliss.” You have to. If it’s deep enough, and authentic and profound and genuine, that’s where you have to go. If you want to put on the collar of a clergyman, go and put it on. If you want to be a barefooted monk in the Himalayas, that’s what you have to do. If you want to be a housewife, that’s what you have to do. Because nature — I know, I found out eventually why I was put on this earth. I was put on this earth to write. And as Thomas Carlyle said, “Happy is the man who has found his work.” So I’m happy, and I hope everybody else finds that, too.

Thank you. That was terrific.

Frank McCourt: Thank you.